|

The apple juiced straight from Eden delicious, intoxicating clink of glasses sips of crunchy red skin how could she predict the fleeting satiation the insatiable desire that she would bear the brunt follow the serpentine path of exile Liz Kornelsen is a prairie poet from Winnipeg, Manitoba and the author of Arc of Light and Shadow: Poems with Art. To dance lightly on the earth in solitude, with other humans, or with other forms of nature, is one of her greatest joys. As soon as I saw her car outside our family’s cabin, I knew this time my cousin Margo had gone through with it. She must’ve seen me coming up the driveway; Margo came out onto the porch and waved until my car settled into the space beside hers. I got out, and she smiled and hopped down the steps to give me a hug. “Patrick.” She wrapped her big arms around me. “I’m so glad you came.” My cousin was bright, bubbly. She was a new woman. Inside, she breezed through the kitchen, pointing out what she had just bought for the place: new utensils, a dish rack, a whole set of dish rags—all of it mixed in with what others had brought over the years. In the sunroom, her arm swept over the watercolor paintings she had hung on the wood-panel walls. “All local artists," she grinned. She led me to the bedrooms upstairs where I’d be staying. “Take your pick.” I pointed at the second room down the hall. She snickered and slapped my elbow. “I should’ve known. You used to hide everyone’s toys there. You had all your little stash spots, remember?” “Sure.” I went in and slid my duffel bag beneath one of the two dusty cots. “It’s weird,” she said. “It’s a different place without everyone else, without all the kids.” She was right. I was used to seeing the rich green of summer out the window and hearing the clamor of young cousins running around. That’s what the cabin was: a place where each branch of the family could come together and be together. Instead, encircled by the golden bloom of autumn, the cabin felt hollow. “Get settled,” she said. “I’ll be downstairs in the kitchen. I hope you didn’t eat yet.” She went to leave but stopped herself and touched my shoulder. “I was afraid you weren’t going to come.” “I could say the same thing to you,” I said. I had been planning to stay for the weekend and only packed a few things. Actually seeing Margo at the cabin though, I wondered if I should’ve packed even less. - I came downstairs to two fingers of butterscotch schnapps. Margo handed me the glass and tilted hers forward. “Just like grandma used to drink.” We each took down the liqueur in a single gulp, the syrupy sweetness coating my throat with burnt caramel flavor. I hated it when I was younger and hated it especially now that I was old enough to drink something else. Margo’s face contorted as she sucked the remnants off her teeth. “That never gets better. I had to keep with tradition, of course.” “Of course.” She put our glasses in the sink, then spun around and clapped her hands. “For dinner,” she began, a playful grin creeping onto her face. “We have beef tenderloin in the oven. Potatoes and asparagus. A nice red. White, too, if you prefer. If you’d like something stronger before, during, or after we eat, there’s bourbon right behind you. I’ve already dipped into that.” She picked up and wiggled another glass filled nearly to the brim with iceless whisky. “It gets my culinary juices flowing.” “Wine is fine for now.” I poured myself a glass and sat down at the table. Margo donned one of the aprons our Aunt Susan used to make each summer. One made of a rich blue cotton had come from a dress our cousin Bethany refused to take back after one of the children tossed it into the lake. Another used to be my old dog Maddy’s blanket, from the summer he ran away. The one Margo chose for tonight had bright orange polka dots, repurposed from a hideous blanket someone had left at the cabin hoping it would disappear. As she cooked, we talked. She asked about my work at the clinic, and I asked about hers at the restaurant. I asked if she had seen our cousin Michael’s newborn; she hadn’t but couldn’t wait. We made vague plans. Only when we exhausted chit-chat did she talk about why she was there. “How’d he take it?” I asked. Margo leaned back against the kitchen counter and smiled. “He knew it was over. I made it clear that it was over.” “What do you think he’ll do now?” She took a sip of her bourbon and threw her hand up. “Who cares. I doubt another idiot will fall for him, not now.” “You’re not an idiot.” She laughed. “I sure am. Staying with that abusive son of a bitch for that long… Jesus. I gave him my best years.” I let it be. When Margo had called the other week and told me what she was going to do, that she would finally leave her husband of twenty-eight years, well, it wasn’t the first time I had received that call. I didn’t really expect her to be at the cabin until I pulled up. We ate in silence. Margo had always been an outstanding cook. “A bad meal,” she had once said, “can ruin a friendship or even a marriage.” She meant it as a joke but cooked as if it wasn’t. After dinner, I cleaned up while Margo put on a record and shimmied around the kitchen, a fresh whisky in her hand. “I love Laura Nyro,” she remarked as she swayed back and forth with each twinkling riff. “Nightcap?” she asked once the dishes were done. “I’m beat.” “Suit yourself,” she said and topped off her glass. “I love it here at night. It’s peaceful in a way you can’t get anywhere else. Like you’re cut off, in some other place where all the BS can’t get at you.” I went upstairs and closed the door to my bedroom. The music still leaked in from below, and I could hear Margo da-da-da-ing to the song. I pulled my duffel out from beneath the cot and opened it up on the floor. Clothes, a toothbrush, a razor, a screwdriver. With the screwdriver, I crawled over to the air vent between the cots. The vent cover was ancient, with layers of paint flaking off, but it slid off the wall easily once the screws were out. I reached back into my duffel bag and pulled out a thin, nickel-plated cigarette case. I gave it a bounce on my palm and felt the weight of its contents shift, then I opened it just to make sure what should be there was there. There were no cigarettes in that case. That’s what Donny at work had discovered when he went looking for one. I had told him to keep what he found there to himself, but after that, I couldn’t have it near me any longer. When Margo called, I saw the chance to get away, to hide the case, to conceal my obsession. I pushed the case into the duct and around a bend then reattached the cover. Lying in bed later, I could breathe easily for the first time in a long time. - The next morning, I awoke to the smell of bacon and pancakes. “I want to take the boat out to Catscratch Island,” Margo said while we ate. “I don’t know, Margo. I was actually thinking of heading out early, maybe try to get up to Eastport before the afternoon.” There was nothing in Eastport, just an excuse. With the cigarette case out of my hands, I wanted to get away from it as quickly as I could. “Don’t give me that. No, no, we will not have Pussyfoot Patrick make an appearance. I like to think you’d’ve grown some balls by now. If you haven’t, lucky for you, the remedy is a dinghy ride over to the island.” Inside, I bristled at my old nickname. Margo stared at me until I sighed, resigned to the plan. “Does it still float?” “Sure does. Jenny and Darren used it last summer. We’ll have to deal with a few spiders but that’s it.” After breakfast, Margo packed a grocery sack with sandwiches and the bottle of bourbon. We walked to the shore. The boat was in a shed beside the lake’s edge, and I dragged it along a splintered wooden track until it tipped and slid the rest of the way onto the water. Margo stepped in and steadied herself. “See,” she said, giving the boat a wobble. “Seaworthy as ever.” I hopped in and took up the oars. The lake’s surface was a mirror, and the tiny craft skated along toward the overgrown acre of land we called Catscratch Island. “Do you remember why we called it Catscratch Island?” Margo asked as I rowed. “Something to do with Aunt Ronnie, right?” “No, Aunt Bonnie. One night I swear she downed a bottle of gin to herself and put on Ted Nugent as loud as it would go so she could hear it by the water. She started pointing to places around the lake and naming them. Said she was going to have all the atlases updated accordingly. The island became Catscratch Island, and over there...” Margo pointed to a rocky peninsula on the far side of the lake. “That became Wang Dang Point.” “Sounds memorable.” “She was so embarrassed every time the kids would bring it up. I don’t think she ever drank again except at my wedding. Looking back, I don’t blame her.” The bow of the boat scraped along the sandy shore of Catscratch Island, and we stepped out. Margo lifted the bourbon out of the sack and offered it. I had a swig; she had two. Then we hauled the dinghy out of the water and let it rest at an angle on the rocky sand. “Look at it,” she said, admiring the tangle of vines and woody bushes that filled the core of the island. “Same as ever.” We walked the perimeter, passing the bottle. “Can I ask you something?” Margo said as we finished our first lap. “Shoot.” “Do you regret your divorce?” I drank and studied the scene across the lake from us. It was midday, and the sun beamed on the orange-blasted trees ringing the lake. The sky just above the leaves was the same rich, clear blue as Bethany’s dress-turned-apron, and in the distance, on the closest section of shoreline, was our family’s cabin. Built, expanded, redesigned, and redecorated, it had never lost its bones. “I don’t,” I said and had another swig. “There were doubts at first, sure, but now I don’t really feel much of anything about it. If we had had kids, maybe it’d be different.” I gave the bottle back. “Do you hate her?” “No. Not anymore.” “Must be nice.” “We had different challenges,” I said. Margo was silent for a moment then stopped walking. “I want to show you something.” “Where?” “Here.” I looked at the wet slurry of sand and gravel at our feet. “Not right here. Up there.” She nodded toward the island interior. I scanned the brush and grass that filled the area. “It’s a mess in there.” “It’s not bad. There’s a trail. See.” She marched up toward a bush and bent her frame around it, disappearing behind spindly branches. “C’mon!” I followed her, and there it was: behind the bush, a thin trail wound inward. “What’s back here?” The island was small, two acres at most, and I felt like with any step, we’d emerge onto the opposite shore. “You’ll see. Here.” She passed the bottle back over her shoulder. I drank. Margo pushed aside a branch to reveal a tiny clearing. Really, it was just a tamped-down patch of dirt encased in shrubs. At one end was a stone, maybe a foot high, but taller than it was wide. Margo stopped and took the bottle back. “Here.” “Here? What’s here? Other than a bunch of ticks.” She drank and then pointed at the stone with the bottle. “This is where we buried him. Where we buried Maddy.” “Maddy ran away.” “No, he didn’t. Michael hit him with his truck when we were coming down the driveway. It was an accident, but we brought him out here to give him a proper burial.” “Is this a joke?” “No joke.” “What the fuck, Margo? What was I doing?" “I don’t know, but this was during your Pussyfoot phase, so we—you know—had to walk on eggshells.” I stared at the stone. “I know,” Margo said. “I’m sorry.” “I loved that dog.” We stood there watching the stone for another minute, then returned to the shore. Margo and I made two more loops around the rocky edge of the island. Occasionally, a stiff breeze would tear past us and break the glass surface of the lake, churning the water into a choppy froth. I wanted to be pissed, though whatever happened then didn’t mean much now. That was the thing about the cabin, all the good or bad that occurred there, it was just another layer. Still, I had loved that dog. - On the last loop, we worked our way across a stretch where rough stones tumbled down from the embankment above us into the water. We paused and sat, polishing off the bourbon until the sun dipped below the trees behind us. We got into the boat and Margo rowed back. Sitting in the stern, I watched the cabin grow larger. The boat smacked the shore opposite just as twilight bled into dusk. “We never ate our sandwiches,” I said as Margo tied the boat off to a post in the water. She laughed. “That’s alright. Throw them in the fridge.” Heading back toward the cabin, we meandered across the lawn, giving each other teasing pushes and laughing like kids. When we arrived at the front porch, I settled into one of the rockers. “I need to rest a moment.” Margo sat down in the chair beside mine. “Why did you wait to show me that? Why now?” I asked. Margo sighed. “I don’t know. I just didn’t want you to not know. Not anymore.” I watched the daylight fade like a flame out of air. For whatever reason, that answer felt right. - I woke up in the dark and found Margo in the kitchen reorganizing the cabinets above the sink. “Look who’s up,” she said when she saw me. “I don’t usually take naps.” “Rest when you need to rest. You’ll be happy to know I’m making my world-famous mac and cheese tonight. I have just about everything, but we need some milk and another bottle of wine. Do you mind running to town?” Margo didn’t mention me going to Eastport. “Not at all.” “Great, the corner store on Route 1 should have everything.” She put down a fresh drink and came closer. “I can’t tell you how much it means that you came,” she said. “You were always my favorite cousin.” I grabbed my keys. The bourbon had left me groggy, but after two wrong turns I found the store. Little had changed since when we were young: the same signs advertising cigarettes and lotto tickets at the state minimum still plastered the windows, and behind the counter a Bush ’92 campaign sticker hung above the clock next to the TV. It was as I was checking out that I really looked at the TV. The news was on, and a reporter was speaking live from outside Margo’s house in Portland. I could recognize it right away even though police cars lined the curb and an ambulance occupied the driveway. The sound was off, but I read the banner beneath the reporter: Portland Man’s Death Ruled Homicide. I blinked, hoping I could shake off some hallucinogenic side effect of bourbon on an empty stomach, but when I looked back up and saw my cousin’s face on the screen, I knew there was no confusion, no mistake. The picture police chose to air—yellowed even through the TV screen—was taken at the cabin. Margo was standing next to a man cropped out, his arm over her shoulder. She’s smiling. “You alright?” The pimple-faced young woman at the counter raised an eyebrow. My stomach had fallen into my feet, and an intense nausea began to creep up my throat. I paid and left. As I pulled up the driveway, the cabin was dark. Margo’s car was still out front, but by now everything was cloaked in moonless darkness. I turned on the kitchen lights and discovered everything in the cabinets poured out onto the floor in heaps of pots and pans and plates. The new utensils that my cousin had brought were scattered on the floor, too. “Margo?” I whispered. On the kitchen table, a bottle of bourbon was more empty than not. “Margo?” Moving into the sunroom, I saw the paintings stacked on one of the recliners; on the other, a shape. And on a table was my cigarette case and the polaroids that had been inside it. “Margo?” The shape squirmed and from under a blanket, my cousin poked her head up. “You’re sick. You know that.” I sat beside her on a stool. “Who are they?” she groaned and eyed the photos. “My patients.” “Why are they like that?” “They’re fine. They’re just sleeping. You shouldn’t have gone into my stuff. Why were you in the vent?” She rubbed her eyes with the blanket and let out a whimper, then tossed something at my feet. “You always had the best hiding spaces.” I picked it up and examined it: a Swiss Army knife, blood dried along the hinge, Hank inscribed on its side. She nodded toward the pictures. “Is that why you came here, why you really came here? To stash those?” I put the knife in my pocket. “It is.” “This weekend, this cabin, this was my last good thing. You know that?” “I do.” “You’re sick,” she said again. “We’re all sick, Margo.” My cousin pushed her face into the blanket and shook her head again. She was still for a while. When I went to stand, she grabbed my arm. “Be with me. Just be with me. Please.” I sat back down and wrapped my hands around hers. We sat in the quiet peace of the cabin, surrounded by artifacts of a treasured past, until the red and blue lights flashed in the distance around Wang Dang Point. Evan Helmlinger is a writer and editor living in Connecticut with his amazing wife, curious son, and lazy cat. He holds a BA in English and History from Syracuse University and has spent nearly a decade crafting, editing, and publishing work that sticks in the mind. Fascinated by the secrets we all keep just beneath the surface, Evan crafts his ideas while folding laundry or working in the yard, later putting them to paper. His work has appeared in Mental Floss, The Humor Times, and elsewhere. My father drank temperately, but occasionally to excess. It made him overtly somber, caustic or sentimental depending on the elixir of choice. He often drank as a means to escape something: the stress of his Wall Street job, Vietnam flashbacks, or my mother’s attempts at cooking a Jacques Peppin recipe. I was not so horrified by my father’s drinking that I was dissuaded to partake in the activity. Scars, to the extent there were any, were hardly noticeable. There would never come a time when I would saunter over to a bar and proudly order a Ginger Ale or Club Soda. Whereas my drinking now involves European lagers and gins filled with botanicals picked by the petite hands of Slovenian children, I was focused on volume in my twenties. I drink in moderation now. I abhor hangovers and dehydration. After graduating from college and moving to Washington, DC, though, I embarked on a period in my life when I was a searching for direction. For the first nine months, I lived with a college classmate named Dave in a high-rise in Crystal City, Virginia, that resembled the set of a Star Trek episode, only filled with bureaucrats and a Korean donut shop on the ground floor. We soon realized we were living above our means, so we moved to more humble one-bedroom quarters in the River Place housing complex, situated in the concrete community of Rosslyn, Virginia just over Georgetown’s Francis Scott Key Bridge. The plan looked good on paper but exposed its flaws when I brought a young Peruvian woman back to the apartment one evening. We were greeted by Dave eating a bowl of cereal in his boxer shorts. My guest thought she had mistranslated a joke when I told her that, at 23 years-old, I was still sharing a bedroom with another man. “Do you guys have bunk beds?” she asked. “Of course not,” I replied. “Our beds are side-by-side.” After some banter with Dave, I brought her back to our room to show her that I was indeed weird and immature but not a liar. It was dark and we mistakenly wound up sitting on Dave’s bed. Dave soon entered the pitch black abyss and hovered inches from the girl’s nose and asked what we were doing. “You smelled like Frosted Flakes,” I begrudgingly told Dave after my friend left never to be heard from again. “She smelled like sin,” he replied. “And you can do better.” After a year, Dave decided to move to North Carolina to pursue a Master’s Degree. It was a bittersweet departure. Dave was more mature than me, or anybody I knew for that matter, including my own parents. He interceded after I nearly threw a haymaker at a Johnny Rockets waiter who had attempted to put a soda jerk hat on me during the staff’s rendition of a Frank Sinatra song. Dave also escorted me once to George Washington University Hospital after I contracted what was diagnosed as a gastrointestinal infection, more commonly known as “food poisoning.” I told the kind nurses at GW that my menu the day before was rather simple: an entire large Dominos pepperoni pizza and give or take 10 cans of beer. I awoke the next morning and had grown rather ill. “I knew it was bad news when I woke up and saw that pitchfork in the corner of the apartment,” Dave said referring to the weapon I had stolen from an unsuspecting woman I had met at a Halloween party the night before. Dave was a bridge between college and the adult world. I missed him but we both knew it was time to move on. I opted to get my own apartment in the same River Place complex. They marketed it as a “hybrid studio.” Depending on one’s view, it was either a 600-squre foot apartment with a bedroom the size of a large closet, or a studio with a closet the size of a very small bedroom. I went with the former concept and used a large United Nations flag that I picked up as compensation from a past unpaid internship as the door. Guests would start squirming after entering my apartment convinced that in 20 years I would be the subject of a moderately-rated Netflix docuseries. I found myself completely alone for the first time in my life. The guardrails were down. And while the independence was liberating at first, I was soon reminded of how much I feared solitude. Freedom was marked by intense stress as I was bound by the chains of self-doubt. I had just landed a job as a writer for a Defense Department journal. In the ‘90s world of apathetic slackers, I was motivated and impatient but had no idea what I was looking for or how to get there. I’d write my stories but they seemed to have little impact on the world around me. My restiveness would hit its peak every Thursday night. Like an old married couple who kept battered copies of the TV Guide in the side of their favorite Lazy Boy, Dave and I were dedicated to our programs when we lived together, namely the famous Thursday night lineup of Seinfeld and Friends. When Dave was gone and I was sitting alone on the same chair Dave had passed onto me as a parting gift, the Friends theme song hit home with a more powerful and disturbing force: So no one told you life was gonna be this way Your job's a joke, you're broke Your love life's DOA It's like you're always stuck in second gear When it hasn't been your day, your week, your month Or even your year ….. In retrospect, my life wasn’t all that bad even though at the time it seemed unfulfilling as I wandered aimlessly and chased unrealistic self-expectations. My job was good but didn’t support my lifestyle, which led to a steady buildup of debt. My love life hovered between disastrous and sporadic but this was more by choice than compulsion. I was attracted to ambitious women but then turned off when their ambitions exposed the reality of my lost soul, a young man who couldn’t define happiness or satisfaction were he asked point blank to do so. Just like the show, I relied on my friends to survive this dark patch, even if they dragged me deeper into the abyss only so that I could find a way out. I’m usually attracted to people who are suffering from the same ills as I am. On weekends I found solace in my college friend Matt and another I had met in DC named James. All three of us were going through the same disquieting experience of being in his twenties. For Mole, the time was a stressful one. James was more relaxed. He was confident we had more time and things would work themselves out, a disposition wrought from being raised an only child. On weekends we drank to make us feel better, in New York, DC or Baltimore, and each excursion offered a window into the quirks of humankind. I was with James one winter night in the Adams Morgan section of DC when I decided that it was time to leave yet didn’t tell anyone. Despite abiding by the mantra of leaving no person behind, I’ve always been a runner when drinking to excess. I would hit a certain threshold of alcohol and I would vanish. I stumbled outside and got into the backseat of the first car I saw. “River Place,” I mumbled as the car sped off. We were driving for about ten minutes when I realized we were heading in an unfamiliar direction and the large cab driver had an even larger friend with him perched in the passenger seat. The car was beat up and had comically false forms of identification hanging from the passenger side sun visor. “Washington Cab Company,” it said in black magic marker. I started to sober up as it was obvious that we were not heading to Virginia and I was in a gypsy cab, an illegal form of livery that would take unsuspecting passengers to a remote location and rob them. It was Uber’s unfinished 1.0 predecessor and one of the frightening hallmarks of living in DC in the nineties. “Oh crap!” I said. “You need to pull over.” “No” the passenger said irritatingly. “I’m going to be sick.” “Bullshit!” he and the driver said. “Bullshit.” “Pull over and let me throw up,” I said while scrambling and frantically feigning terror that I was about to soil the vehicle, which they didn’t realize I could do on a moment’s notice. Everybody has a superpower. They pulled over and I flung open the door and ran, sobering up each and every foot. When I thought I was far enough away I tried to determine where I was, a difficult task in my inebriated state. With no phone to guide me I just picked a direction and started walking. I was desperately looking for a sign when I found myself at the corner of Florida and U, a crime-ridden section of DC at the time. I started to panic and encountered two young men and asked for directions. They too were inebriated but not enough to sense my panic. I explained that a gypsy cab had just dropped me off and I was lost. They offered to help me get me a cab but suggested we get one near the safer confines of Howard University, which was about a 10-minute walk away and where they were students. They were enjoying my description of my close encounter and after we had grown confident that nether party was going to murder the other, they invited me in for a beer. We drank and talked for a few more hours. I’m not sure about the specifics of the conversation, other than that politics and race came up. I remember telling them about the time I lived in Atlanta and went to a classmate’s party. She was black and lived in a bad neighborhood. My mother made me go because she knew none of the white kids were going. My father was skeptical too but ended up hanging out in the driveway talking to neighbors and the classmate’s family, who appreciated that a few of her school friends showed up as most had declined the invitation as my mother had predicted. I had never told that story until then. Alcohol had opened up otherwise forbidden filters. And it was the first time I saw someone moved by my words. I still remembered the details of the event, and told them it had a profound effect on my life, that you can look at the world as cruel and bad or one with hope and promise. If we just kept talking and viewed others with the goodness they offered, the world would be in better shape. And then I pushed too far and my judgment-impaired brain arrived at a conclusion that was unforeseen until that moment. “You know,” I said, “What I think it really means is that black people love me.” The statement did not receive the reaction I had hoped for – laughter mainly. I had not intended to be funny. I tried to pull myself out of the nosedive but only kept descending further. “No,” I said. “Hear me out. When Racquel’s grandmother hugged me she passed something to me.” They howled at my drunken ignorance. The only gift that had been passed onto me before was fear, they observed. They were wrong though. In my twenties, I had no fear. And that was my greatest asset and also my greatest liability. They forgave me for my faux pas, and by the time we finished drinking, it was early morning. I slept on my new friends’ couch. I woke up a couple of hours later and left. It was daylight and my sense of direction was returned in more ways than one. I told the story to Thomas Duffy, an older editor at the journal I worked at. He was framed out of central casting of a 1950s newsroom. He was curmudgeonly and direct but he was a good man and a solid listener who would impart words of wisdom that one would glomb onto. While many young writers were scared of Duffy, my misapprehension of social boundaries prompted me to share my weekend antics with him. He would laugh under his breath while trying not to succumb too much to his childish impulses, which I took as a sign that he should join us. He always declined my invitations, indicating he had given up drinking years ago. “And,” he said, “I’m not going to be your fucking prop when you go out.” He once drove me home after we had covered an event at the Pentagon. As he turned the corner into the River Place complex, I told him that living in such a dismal place was depressing. The job didn’t pay well and every relationship I had was brief and unstimulating. I was unintentionally summarizing the Friends’ theme song. When I opened the door to thank him for the lift, he looked at me and said, “Someday you’ll look back at these days as the happiest in your life. You’ve got time.” My exit from the post-college funk, like the oft-quoted line from The Sun Also Rises, happened “gradually, then suddenly.” It was prompted by a number of factors and events, the most profound of which was when I sat next to the pastor of Georgetown’s Holy Trinity Church, Lawrence Madden, while taking an Amtrak train from DC to New York to attend a party at the New York Athletic Club. Fr. Madden struck up a conversation while he grabbed drinks from the bar car. The priest was gregarious and possessed an inviting aura. He drank and talked with ease and abundance. We spent the entire duration of the train ride doing both. The alcohol lifted the filters and I tackled topics that had bothered me about the church for years, namely the lack of female priests and the Church’s disdain of homosexuality and divorce. As we drank more, I suggested that they serve alternatives to Communion hosts, which were dry and unappealing. “Something, you know, like ravioli or Belgian chocolate,” I said. I also confessed that I was a germophobe and never took the wine because of how many people drank from the same cup. “Why not just have a tray with little servings of wine in cups?” I asked Fr. Madden. I had only found my way to Mass occasionally during my years in DC, mainly when I was living with Dave, a staunch Catholic who guilted me into going. As the train rolled into Penn Station, and we disposed of the impressive collection of bottles that we had gathered during the 4-hour train ride, Fr. Madden implored me to go to Mass the following week. He promised me that his homilies were good because he was a Jesuit, and he specialized in making homilies relatable. Even now, if I like someone, I easily succumb to peer pressure and guilt, especially if the peer was a 63-year old Jesuit. The next week I awoke on Sunday and walked across the Key Bridge and through the doors of Holy Trinity Church. Fr. Madden was right. His was a master liturgist and his homilies were inspiring. During my first visit there, he mentioned me in his homily. Not by name. He just talked about our conversation. He said that he spent four hours on a train ride defending the Church and answering questions from a young man who got bolder (drunker) as the conversation progressed. In reflecting on our conversation, he realized that his answers were imperfect but that he was a better person for being challenged. He had been exposed and that vulnerability had made him stronger. I started attending Holy Trinity more frequently. The summer of 1997 was my last before heading off to law school. I decided that I needed a change of scenery. I had grown to love DC but it’s a transient town catering to the young and the successful. And I was neither at the time. Many of my friends had left to return home to smaller towns or bigger scenes like those in New York and Los Angeles. During one of the last Masses I attended, Fr. Madden talked about one of his favorite New Testament passages. He liked it because it didn’t resonate with just Catholicism, but all religions. It also offered lessons on how to live a life that one day people will remember as fulfilling: Then the righteous will answer him, saying, ‘Lord, when did we see you hungry and feed you, or thirsty and give you drink? And when did we see you a stranger and welcome you, or naked and clothe you? And when did we see you sick or in prison and visit you?’ And the King will answer them, ‘Truly, I say to you, as you did it to one of the least of these my brothers, you did it to me.’ (Matthew 25:36-40) So many stories of alcohol are acts of contrition. For me, it is not. For four years in DC, I acted foolish but I was not a fool. I was a bit lost. Mostly though, I was vulnerable. And while drinking may have been the cause or effect of it, it made me willing to expose my unfiltered self. And it was then, when I was most vulnerable, that I witnessed graciousness. People who welcomed me into their homes, who comforted me when I was sick, who drank and ate with me, and who picked me up when I was down. Before I left DC, I took Communion from Fr. Madden. And then, instead of skipping the offering of the wine, I stopped, took the chalice and drank from it. And I was not sorry. Chris Parent is a writer and intellectual property attorney from Zurich, Switzerland originally from the U.S. His writing has appeared in publications ranging from law reviews to humor sites like Points in Case. His passion is creative nonfiction and he has published essays in Across the Margin, Kairos Literary Magazine, The Good Men Project, Memoir Magazine, and Ginosko Literary Journal. He won the Fall 2020 Memoirist Prize for a story about his early introduction to racial inequality. He is an active member in the Geneva Writers Group and the San Diego Memoir Writers’ Association. Links to a selection of his works and background can be found on www.chrisparent.net.

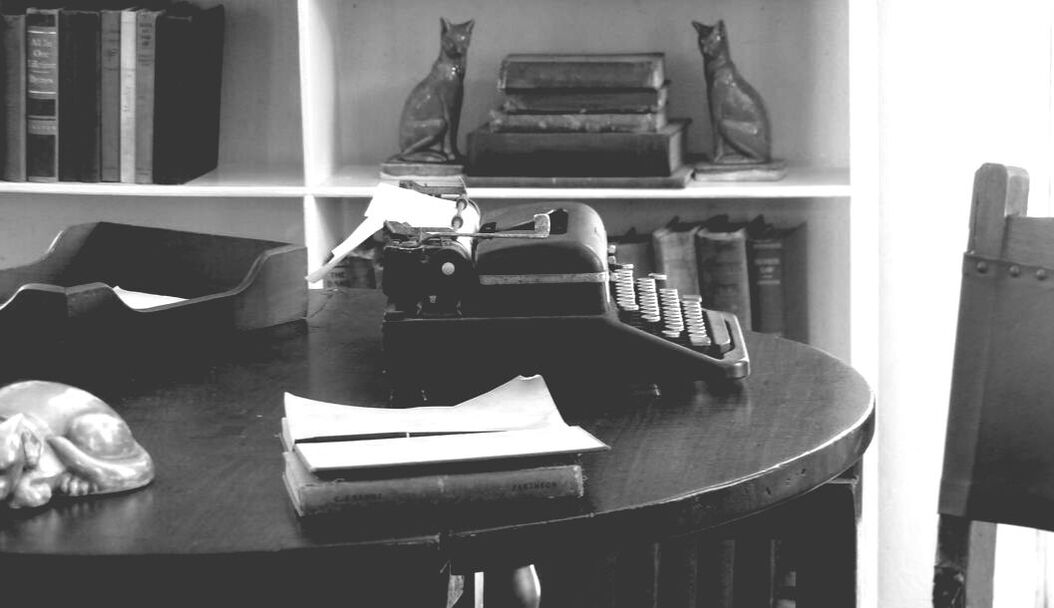

Once, I heard someone say, “You only take your date out to dinner “if you can’t come up with anything more exciting.” Yet, here we sit, in this restaurant, as if we had met only yesterday, but some one hundred years ago, and the place looks exactly like that: modeled after a Philip Marlowe novel. Cherry-oak tables, a bar made from what might be mahogany, thick cushions. Expensive stuff. Even the light, raining from the chandeliers in tiny crystals, seems special. A guy with a fedora sips whisky at the bar, from behind which an audience cheers for us, even though we drink one from their midst, a bottle of cava, solely for our pleasure, because it tastes like a kept promise. We feast on pimientos de padrón, where you never know whether the one you take will burn your tongue. Burrata. Pasta al tartufo. More kept promises. Outside, the trees that line the street are already busy preparing a red carpet made from leaves for the way back to what is now home. When it’s time to leave, the waiter brings the bill: 98.50 in a foreign currency. A hundred and ten, with a tip. And even though I give him the money, I don’t pay for the meal. Maximilian Speicher (https://www.maxspeicher.com) is a designer who writes, mostly sitting on his balcony in Barcelona, watching his orange trees grow. Although he’s been writing poetry on and off for many years, he only recently started submitting it. His first published poems have appeared in Impspired and Otoliths Magazine, and more are forthcoming in The Avalon Literary Review and The Disappointed Housewife. There is such a thing as visual poetry...when a thing need not be said because it is apprehended by the eye and simply "felt"... If a picture is worth a thousand words, how much more so a moving picture? S. Huey (Editor, at Bog Brewing Company, St. Augustine, Florida)

“When spring came, even the false spring, there were no problems except where to be happiest. The only thing that could spoil a day was people and if you could keep from making engagements, each day had no limits.”—Ernest Hemingway: A Moveable Feast Ocean waves wash gently along the beach, where spanned between two sea⸗almonds hangs a hammock. Pearl-white seashore. Paradise. It awaits but no-one is coming. Parrots fly in circles around the island, calling. Rose-ringed parakeets sit on branches, dreaming. Earth’s most beautiful birds await but no-one is watching. Under palm trees, quietly, stands a food cart, empty. Piles of surfboards behind a straw hut. Foamy waves yell eagerly. They await but no-one is surfing. From the trees hang coconuts, mangos, star fruits, figs, and pears; sapotes, pommes⸗cythère, papayas, plums and limes. Earth’s tastiest food awaits but no-one is eating. Inland, there’s a waterfall, just behind the rusty Nissen hut overgrown by vines and moss and orchids. Paradise. It is here but no-one is coming. Maximilian Speicher (https://www.maxspeicher.com) is a designer who writes, mostly sitting on his balcony in Barcelona, watching his orange trees grow. Although he’s been writing poetry on and off for many years, he only recently started submitting it. His first published poems have appeared in Impspired and Otoliths Magazine, and more are forthcoming in The Avalon Literary Review and The Disappointed Housewife. |

Follow Us On Social MediaArchives

December 2023

Categories

All

Help support our literary journal...help us to support our writers.

|

Home Journal (Read More)

Copyright © 2021-2023 by The Whisky Blot & Shane Huey, LLC. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed