|

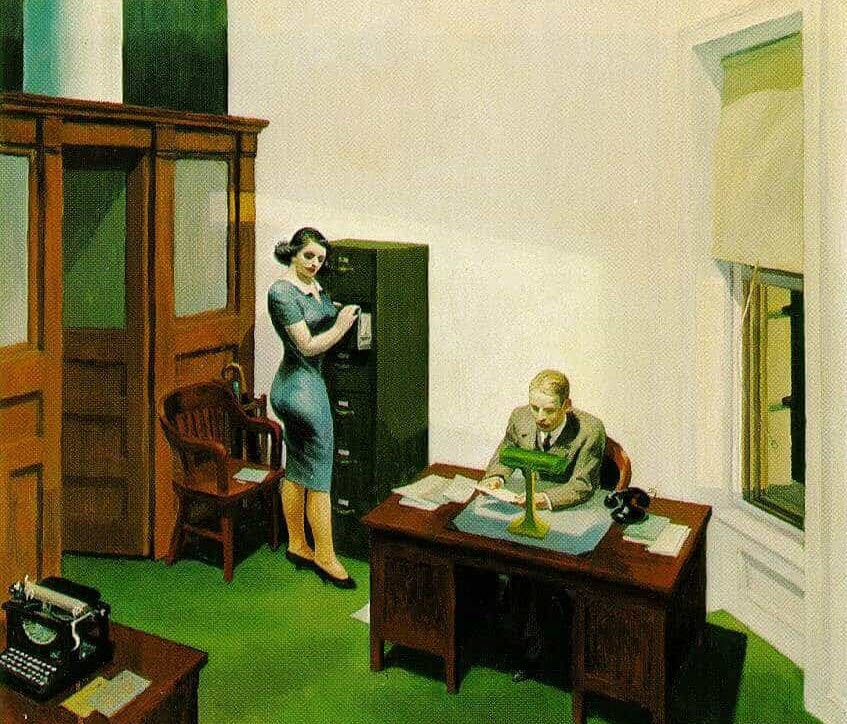

Zelja rested her arm on the open file cabinet drawer and watched over Mr. Garridan’s shoulder as he read the letter for what must have been the tenth time.

She adjusted her tight turquoise dress. She wanted to puncture the long silence and she was comfortable offering him her thoughts. He welcomed her opinion. In work. This was not work. As if finally accepting that no matter how many times he re-read the letter, the contents would not change, he set it down and traced his finger along its edge. He leaned back in his chair and let out a breath. Outside the open window an elevated train blasted by, rattling the frosted windows on the far wall of the small office. “Well, that’s it then,” he said. “What should we do, Mr. Garridan?” He glanced out the window. “We? Nothing we can do. You should probably look for a new position.” “Mr. Garridan, don’t be dramatic.” “I’ll write you a fine reference. Of course, you’ll need to use it quickly, before, well—” he gestured to the letter. “Nonsense. We’ll think of something,” she said. “Not this time, Zel. Not this time. Give me the bottle, will you?” He yanked open the bottom drawer of his desk and pulled out two short stemmed glasses. He loosened his necktie as she eased one of the file cabinet drawers open, lifting it slightly so it wouldn’t screech. She reached to the back, wrapped her fingers around the neck of the bottle. Passing it to him, she saw the contents were below the tiny nail polish mark she had placed on the label a few days before. Garridan took the bottle, made a show of dropping the cap in the waste basket by the window. “We won’t need that,” he said as he filled each glass to one of the gold stripes near the lip. He held one out to her. She stared at his hands, his thin delicate fingers that almost met around the glass. “Zel, I’ll drink alone, but I don’t want to.” He thrust the glass at her. She took it and dropped into the banker’s chair beside the file cabinet. He stood, took a small step towards her and clinked her glass with his. “Noroc,” he muttered. “Ziveli,” she whispered. She brought the glass to her brightly painted lips, the smell of the liquor tickling her nostrils. Garridan drained his glass in one motion and was back at his desk sloshing more alcohol into it. He didn’t notice her lower her glass without taking a sip. He walked to the window, leaned against the jamb and looked at the street below. A stifling silence settled on the office. Zelja stared at her own fingers, plumper than his, tracing the slight imperfections of the hand blown glass. “Could we call Judge Bartholomew?” she asked. “Why would he help me? And what could he do anyway?” “I suspect he’d be sympathetic,” she answered. He cocked his head and looked at her. “His son,” she said quietly, staring at a piece of paper that had fallen to the floor. He made a small noise of acknowledgment and took a long pull on his drink. He turned back to the window. “You and the judge could have lunch at his club,” she continued. “A public show of support.” Garridan didn’t say anything. His silence pulled her to the edge of her seat. “He’s up for re-election next year,” Garridan finally said. “He won’t even want to see me in his courtroom let alone his club. Sympathetic to the circumstances or not.” Another train barreled past in the opposite direction of the first. She wanted to pour her drink out, but the potted plant she had used for the purpose in the past, having withered the week before, had been replaced with an umbrella stand. He gulped down his drink and turned to pour another, but her expression stopped him. “Come on, Zel, it’s just the way things are.” “Well, I hate it. They’ve no right.” He nodded. “Take a sip, Zel. You have to, we toasted. I’ll finish it, just take a sip. For me.” She did. The tiny bit of alcohol burning her throat and reminding her of her father, long gone. Garridan held out his empty glass by the base. She took it, placed hers in his fingers. He drained it in a single swallow and poured another. “Why don’t we just deny it all,” she asked. “Zelja, you keep saying ‘we.’ This is my problem, not ours. Anyway, whoever this is says there’s proof,” Garridan said, pulling his tie the rest of the way off. “Misunderstandings,” she offered. “Depends on the proof,” he said with a laugh. Her cheeks flushed. “Oh bullshit, Mr. Garridan.” “Miss Zastitnik, I am shocked,” he said smiling. “I’m sorry, Mr. Garridan, it just makes me so mad.” “You see, I am a bad influence on you. They’re right,” he said. “I had a father and two brothers. I learned to swear long before I came to work for you, sir. ” He raised his glass in her direction and swallowed again. “What if we had our own proof?” she asked. “Of what?” “Proof that it can’t be true.” “Zelja, one of the first things you learn in law school is that trying to prove a negative is a dangerous strategy,” he said, refilling his glass. “I know how we can prove it,” she said softly. He paused, the full glass mid-way to his lips. “I know someone. A girl. We were in the same boarding house when I first arrived. She would be very understanding.” Zelja stressed the very. He lowered the glass to the desk. “Why would she help me?” Zelja shifted in her seat. “She comes from money. But her family doesn’t approve of her…choices. At some point, they’ll have had enough and no more money.” They sat silent for a moment. “You know how to reach her?” She nodded slowly. “I do. I do.” Garridan exhaled, looked at his glass. Another el train rocketed past the window. “Zelja, I don’t pay you enough.” “I agree, Mr. Garridan,” she said, standing and smoothing her dress. She took a half step to his desk, snatched up the bottle and drank from it, draining it. She put it back on his desk with a bang. “My brothers taught me more than swearing. Put your tie back on. Let’s find your bride.” Michael Klein is originally from New York and has lived in Northern Virginia since 1999. A great fan of bourbon, his tastes are unapologetically simple. He has run a local writers group since 2006 that has produced wonderful talents. Michael has work forthcoming in "After Dinner Conversation." Brenda approached the information desk. The hefty, red-lipped college librarian looked up, threw her head back and sneezed into Brenda’s face. It had just been 24 hours since the mask mandate had been removed inside the campus buildings. Brenda quickly turned as if she had no question. She wanted to ask what time the library would close on Christmas Eve. But all she could think about was getting away from the woman and wondered if the library staff was regularly tested for the COVID virus.

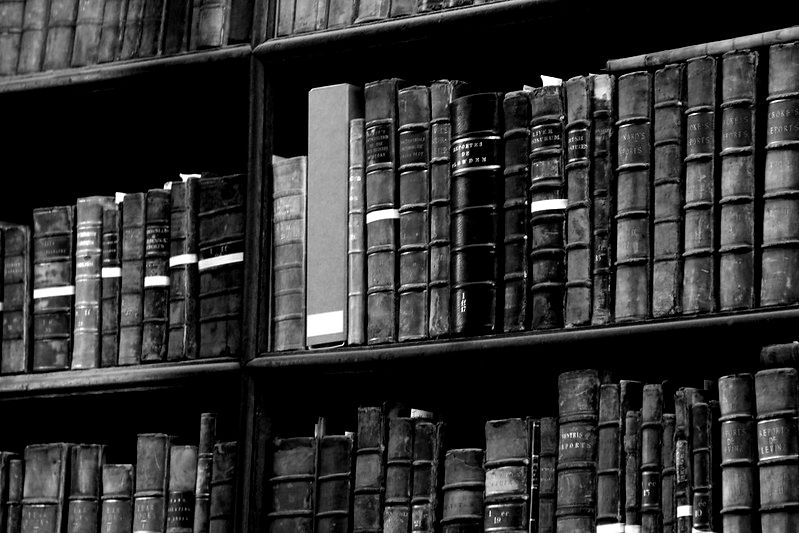

So disgusting, Brenda thought as she headed to the fiction section. She knelt down by the bottom shelf in the "F" aisle and pulled out F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. The slim-necked bottle half-full of brown liquid which she had stashed in the back of the shelf was still there. She couldn’t hide it in her dorm room. Her roommate Greta was anti-drugs and alcohol. And, the RA’s did regular unannounced random sweeps. It was always quiet in the library at this time of day, a perfect hiding place for her booze. She looked up and down the aisle. Satisfied to see no one, she twisted off the cap, and took a long slug of the Jameson whiskey her Irish uncle had secretly given to her last weekend, a week before Christmas. Hot to her throat, yet smooth she thought of Professor McCallam, his salt and pepper hair, his dark sultry eyes, the way he stood at the front of the college classroom full of fire. Her crush had turned into a daydreamed love affair over the last six weeks of Twentieth Century English Lit. She pushed the whiskey bottle to the very back of the wood shelf and replaced the worn edition of The Great Gatsby in front of it. The sound of the bottle clanked somewhere behind the shelving. Oh, shit. Tip-toeing around the corner, she hoped not to be noticed by the careless librarian. She headed to the "J" aisle of the Fiction section. Where had the bottle gone? She bent down, pulled out P.D. James' A Taste for Death, and awkwardly stretched out her arm to the very back and between the cabinets. Her chin on the edge of the shelf, she blindly groped around for anything that felt like a glass container. Did the damn thing break? Her fingers skipped around the wood flooring. Nothing but clusters of dust, and maybe a dead insect. Gross, she thought. She started to pull her arm out. Damn it! She was stuck. Her hand had jammed in the narrow space between the "F" and "J" bookshelves. The shuffle of shoes came towards her. Brown loafers that squeaked a little. Argyle brown and beige socks. Cuffs on the tan chinos. Her head lifted, her knees flush to the floor, her arm strained out, her hand trapped. It’s him! Professor McCallam looked at her, a puzzled grin on his face, his shoulder length straight hair flopped down over his cheeks. "You're in my lit class? Yes?" he said. Brenda felt the sweat break drip under her arms. Her throat went dry. "Brenda Dishtal," she said. In her head it had sounded like Brenda Dish Towel. "Brenda Dishtal," she repeated more clearly. She pulled on her arm but it remained stuck, her wrist bent forward awkwardly, the pain sharp. He looked down at her, his eyes narrowed, the grin on his face gone. "Are you hurt? Can I help?" he asked. He placed his leather briefcase on the floor and knelt down next to her. His after-shave smelled like vanilla. She breathed it in. "Oh God," she said. "I-I was looking for a book and got my hand stuck." He hesitated. "You got your hand…" She interrupted. "I know it doesn't make sense." she spit the words out not knowing where to go with her next comment. "I see," he said, and pulled five or six P.D. James' novels off the bottom shelf, placing them in a pile on the floor next to his briefcase. He reached into the shelving, to the very back of the shelf, his face close to her forearm. She could feel his breath on her skin. She thought she noticed him glance at her arm, which was tanned and golden from outdoor swim practice. His head went further in and came out quickly. "Okay," he said. "Now, I want you to relax your fingers, and let your wrist flop loosely without any resistance. I have no resistance, she thought. “I think, then, I could free you,” he said. “Can you do that? Totally relax the wrist." She saw the slight growth of whiskers on his chin. Tiny gray and black specs. Manly, she thought. His teeth were a translucent perfect white. His gums, pink. Healthy mouth, I like that. The scent of his after shave enticed her. "Yes, I think I can relax," she said. The pain seemed to sharpen, a contrast to her head swimming in ecstasy. “Good,” he said, and pushed a few more books from the bottom shelf onto the floor. He stuck his head back into the narrow shelf space. She bit her lip. "Relax it," he said, his voice muffled. She imagined being on a beach, the professor holding her hand as they moved into the water, laughing as they splashed and played in the turquoise shades of the Caribbean surf. Her wrist went limp. She focused on the back of his head, the beautiful shape of it, his shoulders shifting highlighting the defined muscles under his shirt, as he worked on her wrist. She wanted to touch his hair. He took hold of her forearm just above her trapped wrist. He reached further and gently wriggled her hand, tilting it to the left and up, easing it out of the tight space. She blinked and looked down to see the deep crease across her wrist. No blood. Thank God. He sat up next to her and ran his index finger across the indented reddened line. “How does it feel?” he asked, as he continued to skate his fingers across her wrist. Her mouth fell open. His touch on her skin was like an opiate, one that she might have taken some minutes ago and was on the verge of its full effect. Her mind retreated, her body floated. The whisky shot she had consumed earlier came back to warm her chest again. The professor patted her hand. “Can you move it?” he asked. She stared at her wrist. She didn’t want the time with him to end. She turned it to the right and then left. “Yes, I can,” she said. “It stings a little but I-I think I’m good. she said, her voice cracking. He grinned. “Not broken then, he said and started to rise from the floor. Her eyes locked on the subtle movement of his body as he stood up. His chest lifted first. His long legs straightened. His straight dark hair swung back and forth as he brushed off his tan chinos then took her hand to help her up. She had been rescued by the gallant Professor McCallam, and she was grateful. She stood close to him. His head suddenly jerked back. “Achoo!” He let out a legendary sneeze, his checkered shirt sleeve immediately at his nose. “Dust. I’m allergic to dust,” he said and wrinkled his nose. He held onto the bookcase with one hand. “Achoo!” A more humongous sneeze escaped, shaking his whole body, and the bookcase. Out came the rattling whiskey bottle landing near the P.D. James books on the floor by his leather bookcase. They both looked down at the bottle just as the red lip-sticked librarian came around the corner towards them. “Everything alright here?” the librarian said, strands of loose hair dropping from the red bun on the top of her head. The professor kicked the whiskey bottle behind his briefcase. The librarian came closer. She gave Brenda the evil eye, her lips curled up at one side. “Professor McCallam, hello. Did I hear some kind of loud noise coming from this area?” She smiled, her eyes sweeping from his head to his shoes and up again, a flirtatious smile on her face. “No. No. We’re all good here. Didn’t hear any loud sound,” he said, and pretended to look around. The librarian nodded, and started to walk away, her wide black flat shoes shuffling on the wood floor. At the end of the aisle, she hesitated, turned to take another look at them, shrugged and finally left, her shoes shuffling again; the professor and Brenda frozen in place. “I know this looks bad,” Brenda looked at him not knowing how he’d react. “Tell you what...just to be safe, I’ll take this and give it to you later,” he said. He picked up the whiskey, placed the bottle in his briefcase, pivoted and started down the aisle away from her. “Professor,” she called to him. He turned and raised his eyebrows. His hand went to his chin. “Um, shall I come to your office tomorrow to retrieve it?” “I’ll let you know,” he said, waved and disappeared. Linda S. Gunther is the author of six suspense novels: Ten Steps From The Hotel Inglaterra, Endangered Witness, Lost In The Wake, Finding Sandy Stonemeyer, Dream Beach, and most recently, Death Is A Great Disguiser. Linda’s non-fiction essays and short stories have also been featured in a variety of literary publications.  Almus was awake before the crow of the cock and before the sun lit the black sky grey. It was a cold morning but no colder than yesterday nor any colder than it would be the next. He breathed a sigh and then another. Each breath was a cloud. It was winter in north Georgia. He had never known winter in Miami. He was always up early having never slept much, not as much as he once slept. If only it were an issue of the bladder and not the mind. The bladder, that he could control, but not the racing thoughts, the rehearsed regrets, and the deep sense of anxiety and dread growing within his bones much as shadow at the terminus of day. The floor of the small, old, farmhand house creaked as he wriggled out of bed, first standing and then stretching. Ample crepitus joined in with the cracks and pops in the now daily symphonic performance as two maestros reached harmonious crescendo. The day was here. Soon it would be light. The day always comes. The night always follows the day. Then there is darkness. Always the darkness comes. But there is much work while there is light. Attired in customary overalls, flannel shirt, leather work boots and well-soiled "CAT" ball cap with kettle on the boil, Almus gazed out through the frosted, paned window toward the old, grey barn. For a reason he could not explain, it always made him smile, that old, grey barn. Coffee was instant with sugar. Breakfast, a pastry from the market in town and just up the road. Though not a pastelito of his youth, he ate it and was satisfied. He liked Martha and he liked her cooking and baking. Martha would never know this for he would never tell her. Martha worked at the diner. She was about the same age as Almus and twice widowed he had learned. He thought her tragic. They spoke often when he went into town for a cup of coffee or the occasional dinner and some of Martha's pie. Martha made the best pie in all of Georgia it was said. Apple pie was the favorite. He went there for more than the pie, but he would never tell her. She would never know. Martha enjoyed his visits so but he could never see that. Rather, he would not permit himself to see such things—such thoughts quickly stricken from the mind. He had always been a simple man. Many had hoped, and tried, to find grander substance beneath the gruff exterior and apathetic disposition but he held no facades. He was about as genuine as one could be. Indifferent, yes, but the rough outer layer was a superficial skin worn much as one might wear a misfitted rain jacket. The world only appreciates a certain type of genuine though, and his kind was not that kind. He never needed much and whatever he found himself to have was always enough. This applied equally to people as with things. He did not need Martha. He wanted her. But he did not want her badly enough to need her. He did not want to want her. But he desired things as most men do, for he was a man, but once his desire reached a point he quickly tempered the feeling and convinced himself that he did not, in fact, desire the thing. It was the same with people and things. Everything is effort. Effort which requires a commensurate hope always disappoints. At night, he would think on Martha and of her hazel eyes, her auburn hair, freckled alabaster skin, and how nice it would be to hold someone such as her warm and near as each winter night grew darker, longer, and colder. "Oh Martha..." But he had learned that to need or to want was but to be disappointed. So, he would pour and drink his whisky and then pour and drink some more and try his best to sleep and not to think. The nights passed slowly and then the mornings would come. He would have his coffee each day and look through the frosted window that winter at the old, grey barn across the yard on the edge of fields of high grass, now burned brown by the wind and the cold. The hot, black coffee warmed his insides more so than the fire which had burned out the evening before. It was only cold, just a thing and it did not matter to him. He sipped and stared at the old, grey barn as the sunlight crept slowly into, and soon over, the woods to the east. He watched the play and dance of shadow, of dark and light. The shadow dispersed by light and then light by shadow. The sun rises and sets. The darkness comes and always comes and it is always there, lurking behind everything. He felt it more so today. He saw things as they were and he tried to put this into words but he could not. Feeling it was sufficient. It was just a thing. The barn was old and grey. The oak, hickory, and pine of which it was constructed in a haunted, southern past had greyed at the hand of the elements. It leaned in seemingly all directions at once and, from the outside, seemed upon the verge of collapse. Once a two-story structure, within, the loft had long since collapsed upon the red clay floor and the wood therefrom borrowed to fashion new shutters and double doors for the eyes and mouth of the face of the structure. Internally reinforced with new lumber, Almus had ensured that the old, grey barn was steady and that she would hold, at least for another season or two. It rested upon the frosted ground and seemed as though it had been there forever and would be there a long while more. But Nature always prevails as surely as the night comes and reclaims that which she has but loaned. Such is the way for man and of things. Nothing excited Almus but the one thing and that alone. He had traveled to beautiful places and those places neither impressed nor pleased him. The best of food was but nourishment and brought no pleasure being but a practical matter of sustenance. The finest whisky and wine were consumed by the gulp, neither sipped nor savored. The consolation of whisky was that it at least warmed him and calmed his mind. He liked women but had learned early on that they were not worth the effort. Most men gaze upon a certain woman and, in a moment of magic, know, from the bones themselves, that they could be happy with that woman and if they do not know this thing, they believe it fervently and deep in the heart. Almus saw women through a cataracted lens that brought into view that which is but on the periphery in the healthy eye, that tint and tinge of unhappiness. It was a game of chance that he was too old and too tired to now play. There had been two in his life but they would leave. He was neither excitable nor exciting and he would not commit. He knew that happiness was a temporary thing and that once committed things would change as they are prone to do and then he would be unhappy. He could not be happy today as he was ever occupied upon the imagined unhappiness of tomorrow. When a thing is going too well, you can know that it will soon change…that it will run its course. Love is just a thing. He still thought, on occasion, of Brisa. He had loved her and she him. But he would not commit and she both wanted and needed it as most women do. "We do not need a piece of paper to be together or to be happy," he would often remind her. He would feel himself drawing closer to her and he would say this at that time. He did not see that he was afraid. He was afraid of happiness itself and fearful of the loss of happiness—a vague possibility quietly nestled somewhere in a future that may or may not be. He would not risk it. For Almus, the pursuit of happiness consisted of avoiding unhappiness. He and Brisa were both unhappy now and she left. This time finally and for good. He was unhappy but this would pass. What is happiness if not just another thing? Placing his now finished cup into the stained porcelain, high back sink, he fetched his keys from the wrought iron key rack on the wall by the back door at the side of the kitchen, opened the door, and walked outside. Standing on the first and topmost of the three-steps that constituted the staircase leading into the parched yard, he breathed in the cold morning air and exhaled the smoke, "Ah...” His spirit soared with the cloud. Invigorated and propelled by the energy of the morning, he shut the door, locking it behind him and stepped cautiously down the remaining steps, mindful of the frost and wet. It had rained the night before and the wetness and the dankness hung in the air pressed down upon the land by the thick grey clouds that, even now, lingered close to the earth. What would be called grass in other seasons, crunched under his boots with an almost snow-like quality as he walked toward the old, grey barn. As he drew near the weathered, quiet, and lonely structure, he smiled, if only inside, and his heart pumped a few extra ounces of blood. He spent the length of his days now in the old, grey barn and therein was his sole source of joy. It was the only happiness that he would ever permit himself to experience because it was a happiness derived, not from others in any form or fashion but, rather, a primitive pleasure gained from the work of his own hands and certain things-- things which needed nothing from him in return. He could give as he pleased and be satisfied, unlike with things that need and want and demand. For Almus, this was the ideal relationship. Friends were few and far between these days. Now in the twilight of his years, most were long since gone. His family had all passed. His oldest and best friend from his childhood days in New York gone. One good friend was still there, back in Florida. They spoke from time to time by phone and he received well-written letters from the friend that amused him. But he was truly alone and that was alright. He had convinced himself that he liked it. Loneliness is just a thing. The double doors to the old, grey barn were secured by a heavy chain and padlock. He turned the key in the lock and, lock opened, he loosened and removed the chain from one side wrapping the excess around the opposite handle and pulled the deformed plank doors open and then shut them behind himself. He flipped a switch on the wall and there was a soft humming noise and a few flickers, then a gentle, yellow light suffused the barn. The outside of the structure, old and dilapidated as it was, could not convey that which was to be found on the inside. To be sure, the country barn would meet squarely with general expectation...the bouquet of the country on full display to the nose, the hard-packed, clay floor, displays of fine art by the resident barn spiders, old and rusted farm implements leaning ungracefully in corners into which the soft light could not penetrate as it dangled by its gently swinging cord from a lone, central beam. Resting directly beneath the light as if on display, a lone actor on the cold, dark stage, sat a large object covered by an old and stained canvas tarpaulin. Immediately to either side of the thing were well organized work benches upon which rested tools, each thing in its place. These were the kinds of tools utilized by auto mechanics and, from this vantage point, the inside of the old, grey barn more than less resembled an old-time auto repair shop. There were the rusted barrels and grease rags hanging and floor jacks and cinder blocks and the smell of grease, oil, and gasoline wafted in the cool morning air as it ventilated the barn by means of the many cracks and crevices. Almus carefully removed the tarp to reveal a 1941 Willy's Jeep appearing as though ready to storm the beach at Normandy. It very well could have been there and yesterday at that as it was in fine condition. Olive drab with white lettering, skinny black knobbies, collapsible front windshield and even intact canvas top, the Jeep sat there as it might on the day it had left the assembly line. Everyone has at least one thing, some more, but this was his one thing. He had poured more effort, more money, more time, and the work of his own hands, more so than anything else before, into the Willy's, including the likes of his own, now failing health and failed relationships, and it was his and he was its. Like the old, grey barn, it made him smile. This, to Almus, was more than just a thing. He looked at the Willy's, surveying the restoration. He looked down at his wrinkled old hands, calloused, scratched and battered, grease and grime under the nails, the kind that cannot be removed by soap and water and then gazed back at the Jeep, a product of those same hands. The edges of his lips touched the lobe of each ear and he breathed in deeply and out slowly, the vapor momentarily obscuring his beatific vision of the thing, dissipating into what seemed, to him, a halo before evaporating completely into the cold nothingness of the morning. Before retiring to the Georgia mountains seven years ago, he had bought the old Jeep then looking as though it had, in fact, been to war and on the receiving end of all German vitriol. But he was moving away from the city in which there could be found no good reason to stay. Family and friends had died or moved on, the city had grown too big too fast and had become claustrophobic. He had worked in Georgia once years before and the country with its four seasons and good, simple people pleased him. He always said that he would return and so he did, bringing with him the old Jeep and carefully stowing it in the old, grey barn. Most days and many a night Almus could be found in the old, grey barn working on the aged Jeep. It kept both his mind and his body occupied. Something was broken and he could and would fix it. With each passing day his affection for the ancient and once decrepit machine grew. He identified with it. "You are like me old girl...just like me." He gave her the name, "Acindina" which, in Cuban Spanish, means "safe." Acindina could be fixed, this was possible. Evidenced by the ample and well-thumbed catalogs about the work benches and the empty, neatly stacked, corrugated parts boxes, Acindina could be rebuilt and had been, save a thing or two here and there. But his old body could not. Not now. The doctors in Miami had tried. Each day the old lady grew more to resemble her once glorious, former self. Each day the viejo (old man) did not. Almus had once himself been in pristine physical condition for his age and of this, before his retirement, he would often boast. His family had "great genes" he would say and most of his ancestors had in fact lived well into their nineties. He was but sixty-seven and his health had taken a drastic turn. There was the complete and total loss of hearing in one ear, hypertension, sudden onset of a rapid heartbeat, the recent diagnosis of sleep apnea, he was born missing a kneecap and this, offsetting his gait, did not help his advancing arthritis nor the compressed discs in his spine from the automobile accident that had almost killed him. But he walked more now, about the fields and through the woods behind the old, grey barn, breathed the fresh mountain air deeply, and took his medications. He was old now and knew it, what more could he do? Even health, a thing neglected when well and felt deeply when poor, even health was but a thing and, "It is what it is" he would say. All things are just what they are. This was not apathy but acceptance—acceptance of truth or tautology but, nonetheless, a matter resolved to great satisfaction in his own mind. Today, he eagerly awaited the post, which ran early most days on his road, for the last few pieces of his puzzle, heavy-duty, front and back differential covers for the Willy's which arrived mid-morning. The carrier knew where to deliver anything of a size greater than an envelope. Almus unpackaged the parts with shaking hands, separated the covers from the gaskets, inspecting all and finding it satisfactory. Unfurling an oil stained, chamois cloth and carefully placing the pieces upon one of the tables beside the Jeep, he then surveyed the array of tools and grabbed a handful of various wrenches, sockets, and a putty knife. He reached low toward the table bottom and pulled out a dented, aluminum oil drain pan, placing the tools in the pan, slid them underneath the frontend of the Jeep. He grabbed a large, filthy towel from a bent nail functioning as hanger and laid it out beneath the Jeep and returned to the table once more, rummaged through a bucket of spray cans and tubes for a can of Brakeleen, can in hand, sliding underneath the vehicle. "Damn it!" he exclaimed aloud realizing that he had forgotten a light. He scurried from underneath the Jeep, returned to the table, and back again beneath the Jeep, finally, in similar scurry this time with lantern in hand. He turned on the lantern and stuck the magnetic base to the axle and adjusted the light so that he could clearly view his work space. He slid the oil drain pan immediately underneath the front differential and began to loosen the bottom drain bolt, which would not budge. He reached for the Brakeleen and sprayed it around the bolt hoping that this may loosen its grip, one which had been firmly anchored in place, no doubt, since 1941. Moments later he tried again to no avail. He would try again and again, with all his strength and weight, both substantial, and yet the bolt would not turn. He became increasingly worried about the bolt stripping and that would be a dire situation to remedy. So he slid out from underneath the Jeep, stood, permitted his breath, which had become short under the exertion, to return to him and he thought. Returning once again to the bucket of mechanical balms, salves, and liniments, he retrieved a can of WD-40 and pulled a rubber mallet from the wall and back underneath the Jeep he went. He dried the bolt, removing the residual Brakeleen as best he could with his pocket rag and then sprayed the lubricant on the bolt. "There, just give that a minute." Again he tried the bolt but it would not move with wrench and leverage so he attempted percussion upon the wrench with the mallet. Still, it did not move. He grew frustrated and, as most men are prone, when frustrated he was more inclined to act carelessly and thus he remounted his mission with all of his force and might...pulling on the wrench, torso off ground with all of his weight into it. Still it did not move. More percussion. It did not move. More strength and weight until, finally, the bolt gave but not as hoped. It was stripped. Alumus laid on the ground, exhausted and short of breath. His heart raced and he felt lightheaded. He tried to maneuver himself out from underneath the Jeep but his left arm and chest were suddenly racked with pain. He looked for something that might have fallen loose from underneath the Jeep...something large and heavy, it had to be an elephant, but there was nothing there but the pressure. He could not move now gripped by pain and a growing anxiety. The pain was now radiating into his neck. Everything felt as though being squeezed by an invisible but cold and mighty hand. It hurt and it hurt bad. The breath grew shorter and shorter and he now felt as though trapped in a tomb underneath the Jeep, the space growing smaller and smaller and tighter and tighter as did the grip upon his heart. He was afraid. He had never felt such pain. Still he could not move and he gasped for a full breath all the while his heart racing faster and faster and, hand upon chest, the many beats of his heart so close together as to feel as though a singular and perpetual pulse. And here it now was—he laid there dying, on the cold, clay floor of the old, grey barn this dark winter's morning, entombed as if buried alive beneath the chassis of the old Jeep. The movie of his life did not play for him as is often said to so do. Had it played, it would have been short, silent, and in black and white. He thought his last thoughts and spoke his last words to himself alone. The pain became terrible and he clutched the area above his heart, arms crossed, and he screamed and he hurt. He attempted to roll to one side, perhaps that might bring some ease, but the effort was in vain for it was his last action and he did not complete it. And then the old, grey man lay on his back again, breathed his last and the steam of life's breath passing now into death dissolved into the cold air of the old, grey barn. They say that one dies much as he lived. In the end, death is just a thing. First published in Purple Wall Stories. |

Follow Us On Social MediaArchives

December 2023

Categories

All

Help support our literary journal...help us to support our writers.

|

Home Journal (Read More)

Copyright © 2021-2023 by The Whisky Blot & Shane Huey, LLC. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed