|

Jeffrey Dickerson spins the Tahoe’s steering wheel and turns off the highway onto an overgrown and barely visible dirt track. I’m surprised I can still find this place after more than 50 years, he thinks. The SUV moves slowly across a meadow, flattening the road’s vegetation as it passes, and continues into the pine forest. Under the dense canopy, no sunlight reaches the ground and a somnolent gloom envelops the vehicle and Jeff.

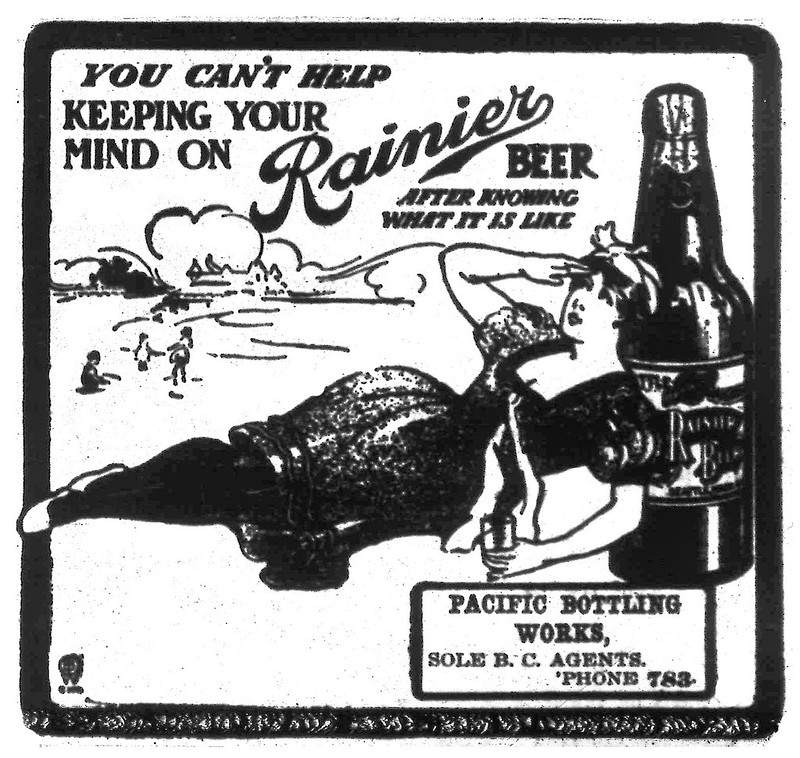

Geez, we used to do this at midnight, drunk on booze swiped from my stepdad’s liquor cabinet. The grasses and undergrowth disappear and he follows the eroded Jeep trail past trees that have doubled in diameter since his last visit to the lake. At a clearing, he pulls up and kills the engine. A strong wind down from Canada whistles through the pines, cooled by snows off the Cascades. A thick blanket of needles covers the ground, free now of the beer cans, candy wrappers, used rubbers, and assorted trash that Jeff remembers from his youth. I guess nobody comes here to make out anymore. But then why would they after the mills closed and the town emptied. He pulls on a down jacket and wool cap, wraps a scarf around his neck and sets out, following the memory of a trail that has all but disappeared. Jesus, if I get turned around out here, nobody will ever find me. But in a few minutes the wind freshens and he sees sunlight shining off the lake. He strides out of the forest onto its stony shoreline. The surrounding mountains haven’t changed, snowcapped, ever watching. He sits on a boulder and breathes in the fresh citrusy-smelling air, so much different than the bluish-white haze along LA’s freeways. But the cold seeps into his bones and his arthritis screams for relief. He pops a Norco and washes it down with a shot of Jack from his pocket flask. His body gives a huge shudder, then settles. Jeff waits for the pain drugs to hit before pushing himself up and moving off down the shoreline, slipping on the stones and swearing. At a particular spot, a rock formation juts into the lake. As teens, he and his buddies Terry and Leo ditched their clothes, picked their way to its end, and dove into the crystal clear water. The cold felt great on hot summer days. But this autumn day, Jeff turns away from the lake and into the forest, mumbling to himself, counting steps. At 25, he looks around. Two gigantic ponderosas stand guard over a mound of granite. At the rock’s base, he lowers himself to his knees. He scratches away the carpet of needles, withdraws a garden trowel from inside his jacket and begins to dig, carefully. In a few minutes he hits something. Digging now with his trembling hands he uncovers and withdraws a mason jar, its lid corroded but intact. The jar’s glass has frosted over. He tries removing the top but it won’t budge. In exasperation, he taps it against the rock. With a tinkle of glass the jar shatters. Jeff reaches forward and picks up two cards, one a Washington State driver’s license, the other a tattered Social Security card. He stares at the license. Jeff’s young image stares back, his somber face next to the name Roger Stokley. *** Roger smeared Sea & Ski on his arms and face, and watched Terry and Leo repeatedly plunge from the rock jetty into the lake. He clasped a Rainier Ale between his thighs; the cold can felt great in the August heat. Leo had swiped a couple six-packs from his father’s grocery store. The friends had vowed to spend the last weekend home after high school graduation getting drunk on whatever they could scrounge. The two friends joined him on the stony shore. “You better not have guzzled all the beer,” Terry chided. Roger grinned. “Nah. I’ve left ya a can or two.” “Where the hell did the church key go?” Leo complained. “Relax, it’s in the cooler.” Shivering, the two swimmers dried off, sat next to Roger sipping their beers, and stared at the lake, its waters glassy calm. “So, you all set for Nebraska?” Roger asked Terry. “Yeah, I guess. I’m on the bus Monday. Classes start the next week.” “Can’t believe you’re goin’ to U of N,” Leo said. “I think they’ve got three trees in the whole damn state.” “Hey, I gotta go where they accept me. That’s the deal. And do you think Montana Tech is that much better?” Leo grinned. “At least they’ve got mountains and trees.” “What about you?” Leo asked Roger. “Got it figured out? You need to get into school or they’ll draft your ass and send ya to Viet-fucking-nam.” “Yeah, well I’ve had enough of school. Don’t like it much.” “But, if you don’t at least enroll somewhere you’ll—” “I get it, I get it. I’ll figure it out.” But Roger didn’t have a clue about what to do. And his stepdad wanted him out of the house, to make way for a new girlfriend so they could fuck all day long without Roger snooping around. His stepdad didn’t care what Roger did, just wanted him gone. An uncomfortable silence settled between the friends. Roger realized that this could be the last time he and his pals hung out. The afternoon wore on. Their clutter of empty beer cans grew. They dozed in the golden light, faces burnt a wild cherry red. Groggy, with a headache coming on, Roger woke. “Gotta pee,” he muttered, pulled on his shirt and pants, and stumbled into the forest. He stopped at a mound of rock framed by two young pines, unzipped and wet the stone with four beers worth of piss. As he finished, he noticed something strange. A pile of neatly folded guys’s clothing and a pair of shoes rested near the top of the rock. He scanned the forest but failed to spot any naked guy wandering around. Maybe he’s swimming in the lake? But we’ve been here all day and have had the place to ourselves. Pine needles covered the shoes and a long-sleeved sport shirt that topped the pile. Totally weird. Whoever left this stuff must have split days ago. Roger carefully slid the creased slacks loose and checked the pockets. No car keys. How the hell did he get here . . . or leave? The buttoned-shut back pocket held a wallet. Roger sat on the ground, his heart racing, and looked through each compartment. The wallet held 96 dollars in small bills. A driver’s license belonged to Jeffrey R. Dickerson, 21, of Tacoma, Washington. Roger stared at the license and at the photo image. What was this guy from Tacoma doing around here? Jeff was close to Roger’s height and weight with the same color eyes. But Jeff had a thick walrus mustache. Roger continued to dig through the wallet. He found a Selective Service Notice of Classification card that showed IV-F. A grin split Roger’s face. Not only does this guy look a little like me, but he’s old enough to buy booze and won’t get drafted. An escape plan formed in Roger’s mind: I’ll become this guy and lamb on out of here. Go south to Frisco and get lost in the hippie scene, that Summer of Love shit. Roger’s mind filled with all the details that had to be worked out. But at least now he had an idea, one that just might work. He took the wallet and slid it into his pocket, scraped the dirt away from the base of the rock and buried the clothes. When Roger returned to the shoreline, Terry looked at him and laughed. “That was some pee. What were you doin’ in there, jerking off?” “Nah,” Leo cracked, “he wouldn’t take that long.” “Come on, fools,” Roger said. “We gotta go.” The trio checked the beach to make sure they hadn’t left anything behind, then hustled down the well-worn path to the clearing and piled into Leo’s Ford Econoline van. On the way back to town they didn’t say much, sleepy from the beer and not really knowing how to handle their goodbyes. Finally, Roger broke the ice. “Hey Leo, you takin’ this piece-of-shit van to Montana?” “Nah, my Pop needs it for the grocery.” The silence returned and when Leo pulled up in front of a ramshackle clapboard house, Terry bolted from the van, rubbing his eyes. “Give ’em hell in Nebraska,” Leo called after his retreating friend. Terry waved his hand but didn’t turn around. He disappeared inside the house. When Leo got to Roger’s singlewide trailer, he turned the engine off and swung around to face him. “Look, I don’t leave for Montana for a week. If you need help figuring shit out let me know. I know you’re freaked out about it. I would be too.” “Yeah, thanks. But I’m workin’ on an idea.” “So what is it?” “It’s better that I keep it to myself. But don’t worry, I’ll be all right.” “Cool. Glad to hear you got somethin’ goin’.” “So, I’ll see ya, man. And say hi to your Pop for me.” “Yeah, Roger, sure. Stop by the market anytime. I’m sure he’d like to shoot the bull with you.” It took Roger over a month to grow a walrus mustache. He trimmed it to look just like Jeff Dickerson’s. One Sunday in September, when his stepfather had taken his girlfriend out for a drive, Jeff gassed up his beat-to-hell Volkswagen Bug. He stowed his guitar and a battered suitcase full of essentials and headed to the lake for what he planned to be the last time. Hustling into the woods he removed his driver’s license and Social Security card, placed them in a Mason jar, and buried them next to Jeff’s decaying clothes. If anyone ever finds this stuff, they’ll think it’s me that disappeared. At that moment, Roger Stokley felt he’d become Jeff Dickerson. He ran to his car and raced back to the two-lane highway that led south toward the Interstate. After a pedal-to-the-metal dash across Oregon, he motored into California, pushing even more frantically southward, toward the City by the Bay where the hippies and other remnants of the Summer of Love took him in. *** Groaning, Jeff Dickerson stands and slips his old driver’s license and Social Security card into his shirt pocket. He kicks dirt over the shattered Mason jar and walks back toward the lake. At the shoreline he stops to stare at the high storm clouds rolling south. It might rain and snow that night. On the far shore, brightly colored kayaks and canoes are stacked in racks on a dock that serves a lakeside resort. The huge complex looks closed for the off-season. This place must be a circus during the summer. A gust of frigid wind hits and Jeff moves off, finds the trailhead and returns to the clearing and his welcoming Tahoe. Inside, with the heater blowing full, he stares once again at his old driver’s license picture. Well, I’ve done it. But what was I expecting? Some sort of magical return to my former self? So stupid. Everybody I knew is dead or close to it, including the whole damn town. Back on the State Highway, he approaches his hometown. The Internet pictures he studied showed a place just a few years away from becoming a ghost. Now, driving down the main street, the forest has already reclaimed some of the stores and houses. The last mill shed at the north end lies broken, its ridge rafter sagging, with berry vines claiming the rest. The hotel leans ominously with graying particle boards nailed over its doors and windows. Jeff cruises the back streets, dodging monster holes that pockmark the crumbling asphalt. Terry’s house has disappeared under a mound of creepers. A similar mound occupies his stepdad’s property. One end of the ancient trailer still feels sunlight, its roof gone with fire burns licking up from glassless windows. But Leo’s place stands in good repair, a satellite dish on its roof and a propane tank in the side yard. On the corner of the main street, close to the highway, stands Owens Grocery. A couple neon beer signs glow in its small-paned windows. The single Gulf Oil gas pump has been replaced with a modern Chevron pump. Could Leo’s family still run this place? God I’m thirsty . . . could use a cold one. Jeff parks out front, climbs onto the wooden porch and enters the store. A bell rings over the door. He shuffles across the worn wooden floorboards to the counter. A middle-aged man sits staring into a smart phone, grinning. He looks up and smiles. “How can I help you this afternoon?” “You guys sell Rainier Beer?” “Sorry, mister. We have Bud, Coors, Miller, Moose Head and a bunch of boutique beers. But no Rainier.” An old man slumped in a corner chair next to the Franklin stove mutters, “We haven’t sold that swill since the seventies. The brewery got bought up and moved to LA.” Jeff sighs. “That too bad. Me and my friends used to drink that stuff out at the lake.” The old man unfolds himself from his chair and hobbles toward him, his right hand clutching a cane, the left hand and arm hanging limply by his side. He moves in close, removes a filthy baseball cap and stares up into Jeff’s face. “Well I’ll be damned. Roger Stokley, right?” For a moment Jeff stands frozen in place. He hasn’t been called Roger since he fled after high school. He doesn’t know whether he wants to reveal such a long-held secret. Can they put him in jail for impersonating someone else; for prematurely drawing Social Security under a false name; for failing to notify the police when he found the wallet? And his children, what would they think? Would it get back to them and his ex? And does he really want to open that trap door into his past? The eyes that stare into his look young. He lets out a breath and grins. “Is that you, Leo?” “Who else would hang around Owens Market? Come on, pull up a chair and let’s talk. Jesus, I never thought I’d see your sorry ass again.” “Yeah, us Stokleys are tough, real survivors.” The old men sit next to the radiating stove and sip beer brought to them by Leo’s son, David. “Dave keeps this place goin’,” Leo says, beaming. “He makes his money as a software designer out of our family’s old place. His kids are in college and his wife and I get along great. Got my own room and shitter. What more can a man ask for?” “Yeah, I’ve driven by your place. It’s the only one that looks occupied. What the hell happened here?” “What do you mean? We saw it start while we were in high school. The mills closed and folks moved out . . . some just walked away from their homes.” “But you’re still here.” Leo flashes a lopsided grin. “Near the end of my second year at Montana Tech Pop had a stroke; must be hereditary. I came back to help Mom run the store and take care of Dad. Both of them have been gone for decades. But I never left.” “How do you do it?” Jeff/Roger asks. “The off season is tough. But they’ve subdivided a big patch of forest a few miles easta here and built all-season homes. Enough of the folks overwinter and we’re the only store out here.” “Yeah but . . .” Leo continues. “They’ve built a big resort on the lake that operates from early spring through Halloween. I get lots of business from the tourists and the resort itself. And they put in a huge KOA back in the woods from the lake. Folks stay there for weeks and need supplies.” “But . . . but you were gonna be a mining engineer, travel the world and make big bucks as a consultant. And you have a wife?” “Had. Elaine couldn’t handle the isolation of the great north woods,” Leo says, laughing, and gulps his beer. “We divorced when David was in high school. Haven’t heard from her in years. She’s down near The Dalles somewhere. Either that or dead.” The heat from the stove and the beer calms Jeff/Roger and he slumps in his chair, relaxing for the first time on his trip up from LA. “So . . . I drove by Terry’s house. Gone. What happened?” “Good ole Terry lasted less than a year in Nebraska. He quit school and joined the Marines. He’s fertilizing some rice paddy in the Mekong Delta. His folks moved away, just left the house one night with all the lights on and the front door wide open.” David replaces their empties with fresh cold ones. A comfortable silence grows between the two men. The fine tremor that has shaken Jeff/Roger during his long trek north has calmed. Finally, Leo speaks. “Aren’t ya gonna ask about your stepdad?” “I’m curious, but I don’t really care. There was never any love lost between us.” “Yeah, I get that. He lived in that funky trailer with various women for a few years after you left. Then a pissed-off girlfriend doused him in booze and lit him up. You probably noticed the burn scars on the place. He died shortly after that. Your place and most of the others were taken over by the County for delinquent taxes. A while back they held an auction trying to sell ’em, but got no takers.” “Huh,” Jeff/Roger mutters. “So . . . I’ve been blabbering on this whole time. What the hell happened to you? It’s pushin’ sixty years since you left.” Jeff/Roger sucks in a deep breath. Should I tell him the truth? Who can it hurt now? Everybody’s gone or dead. He takes out his old driver’s license and hands it to Leo. “You kept your old license? Jesus, ya look like some wise-ass hippie punk.” “Yeah, I suppose I was.” Jeff/Roger removes his current license from his wallet and hands it to Leo. “What’s this? Who the hell is Jeff Dickerson?” “It’s me, man. It’s me.” Leo stares at him wide-eyed. “What the fuck you talkin’ about? You’re Roger Stokes. We used to go to the lake and mess around, drink Rainier.” “Yes, I remember,” Jeff/Roger says. “That last time at the lake, I found a guy’s wallet back in the woods. Stole it, stole his identity and split to California, talked them into giving me a driver’s license.” “Holy hell, you’ve lived someone else’s life all this time?” “No. I’ve lived my own life . . . just under a different name. And it paid off. The guy was three years older than me and IV-F. So I could buy booze, avoid the draft, and decades later sign up for Social Security three years early.” “And the guy never turned up?” “Beats me, I’ve never looked. My bet is that he drowned in the lake and they never found him.” “Why do you say that?” Leo asks. “Along with his wallet I found his clothes. Could have been a suicide. The guy was from Tacoma.” Leo’s eyes grew large. “Ya know, about fifteen years after you left, a big storm churned up the lake. Some hikers found human bones along the shoreline. Never did identify who they belonged to.” Jeff/Roger grins. “Well, by then I was livin’ in LA with a wife and two kids, teaching math to high school students.” Leo’s mouth dropped open. “You, a teacher? You hated school.” “Yeah, well forty years of that was enough. My wife left me and my kids are scattered. I guess I’m searching for a place to land.” “Maybe an old place?” Leo grins. “Maybe.” “So . . . so what should I call you?” “Call me . . . Roger. I’ll claim it’s my middle name.” “Cool.” “But . . . I’ve gotta go back to LA. Gotta take care of business, ya know.” Leo nods. “Will we see ya up this way again?” “When you start stockin’ Rainier Beer, I’ll consider it.” “So you’re not coming back?” “I’m . . . I’m Jeff Dickerson of Pasadena, California.” “Yeah . . . Jeff. Thanks for stopping by and . . . I’ll catch you later.” Seems that Leo has gotten better over time with goodbyes. Jeff pushes through the market’s front door. The bell tinkles. Back in the Tahoe he heads south, retracing his 1967 flight. After visiting his past, he knows that’s not where he belongs and that Thomas Wolfe is right. Terry Sanville lives in San Luis Obispo, California with his artist-poet wife (his in-house editor) and two plump cats (his in-house critics). He writes full time, producing short stories, essays, and novels. His short stories have been accepted more than 490 times by journals, magazines, and anthologies including The Potomac Review, The Bryant Literary Review, and Shenandoah. He was nominated twice for Pushcart Prizes and once for inclusion in Best of the Net anthology. Terry is a retired urban planner and an accomplished jazz and blues guitarist – who once played with a symphony orchestra backing up jazz legend George Shearing. Comments are closed.

|

Follow Us On Social MediaArchives

December 2023

Categories

All

Help support our literary journal...help us to support our writers.

|

Home Journal (Read More)

Copyright © 2021-2023 by The Whisky Blot & Shane Huey, LLC. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed