|

Travis listened to his wife Britany’s phone call. He winced. “DFS is visiting tomorrow. Now I got to clean this shithole tonight and go do laundry. That bitch social worker is gonna want to see we have some food in here,” she snapped after she hung up. Travis took a wad of rumpled one-dollar bills from his pocket and handed them to Britany. There goes my beer money, he thought. She counted all seven of them out, slamming the skinny stack on the battered coffee table. Britany glowered at him. “We need eggs, meat, fresh greens and some fruit by tomorrow, or they’ll take the kids to foster care,” she snapped. Well, maybe you should have used the EBT card for food instead of selling it for meth money, he thought. “I’ll get some meat tonight. Bowen will give me twenty bucks for tenderloins and backstraps,” Travis said, as he pulled on his Carhartt jacket and wool skull cap. “We can’t risk you coming back empty again. I’ll go get a quick fifty from Jimmy,” she said standing up. Travis flew across the small trailer living room, kicking his son’s toy truck from the boy’s hand as he lunged for his wife’s throat. His son pulled his younger sister away from the fray. Britany’s eyes widen as Travis firmly held her by the throat. “I ain’t no goddamn cuc for a meth whore. You go to him, you stay with him.” ## As the late afternoon sun painted the November sky streaks of burnt orange to the west, Travis drove down Old Mill Parkway. The road ran through a half dozen corn or soy fields then a stretch of woods along the river before it passed a new gated community of mini mansions. This close to rut the deer should be moving and some rich asshole might hit one on their way home, he reasoned. Within the first two miles, Travis found two mangled doe carcasses. Both were too old and had gone off. Travis turned onto County Road 22; he’d return to Old Mill after traffic hour in hopes somebody got unlucky on their evening commute. He knew roadkill would be harder to find out on 22, but he had a decent chance of running a deer down. Last summer, after he got probation for spotlighting deer, Travis reinforced the inside of his front bumper with steel plates he boosted from a construction site. Then he welded the bumper directly to the frame of his 1997 F150, turning it into a battering ram. Travis installed a extra bright LED light bar on his hood to “freeze” deer. Not allowed to legally hunt or own weapons, his truck was his only weapon to kill deer. Originally, Travis modified his truck hoping to run down bucks. Over his years of poaching, he had built up network of taxidermists like Bowen willing to buy buck racks, hides, and prime cuts of meat. He’d hoped the truck would provide him with stew meat and booze money. He sped through the straight section of the road that lined farm fields, knowing deer would see him coming. When the road began to follow the river, he slowed and clicked on the LED lights, hoping to catch a deer crossing. Nothing. Where the fuck are all the deer? He took County Road 34 back to the Old Mill Parkway. He spotted a buck on the shoulder, but his corpse had already gassed up. Travis pulled over. It was a decent 10-point buck. He took his Sawzall from the cab and cutoff the buck’s skull cap. Bowen will pay at least $15 for this rack, he thought. As he drove back down Old Mill Parkway, he prayed, Come on God, give me some meat. A few minutes later, he saw it; a freshly dead doe laid just off the road in a drainage ditch. Travis pulled off the road, grabbed his hunting knife, and went to work. It took him about 10 minutes to cut the backstraps, tenderloins, and hams and shoulders free, and wrap it all in a clean tarp in the bed of his truck. He’d skin the hams and shoulders back at the trailer. He texted Bowen—I’m headed your way with meat and a rack. Have cash. ## Travis left Bowen’s with $40 and two road beers, not counting the one he drank bullshitting with Bowen. He made his way to Kroger and picked up eggs, milk, potatoes, cereal, apples, greens, and a few staples. He had just enough cash left to stop at the gas station for a 40oz of Bud. When he pulled up the trailer it was dark. Britany’s beater wasn’t parked out front. Travis quietly opened the unlocked door and went in. In the glow of the TV, his son and daughter slept on a sleeping bag on the cold floor. He put the groceries away. Then went to cover his children with a blanket. As Travis bent over them, his son woke and hugged his neck. “Mommy went to Mr. Jimmy’s,” he said. Travis drew him closer. “That’s alright son, I got us a bunch of food… I got you your favorite cereal for breakfast. Go back to sleep.” Travis kissed each child on the head. He opened a beer and headed back to his truck. He took off his jacket despite the cold and went to work skinning the deer quarters. As he worked, he decided he’d make venison stew for supper tomorrow; he’d even offer a bowl to the DFS social worker. He’d ask his ma to watch the kids tomorrow night. It’s roadkill season, he said aloud. JD Clapp is based in San Diego, CA. His work has appeared in Micro Fiction Mondays Magazine, Free Flash Fiction, Wrong Turn Literary, Scribes MICRO, Café Lit, among several others. His story, One Last Drop, was a finalist in the 2023 Hemingway Shorts Literary Journal, Short Story Competition. I love simplicity. Life can be very complicated and stressful but if we made things simple, everyone would be happier. I have a flat with a subsidised rent; a steady job as a warehouse packer; my rent and bills paid by direct debit and enough money for a pint or two each week. I’m walking distance from work so don’t have to worry about commuting and I have access to all the books I need at the local library. I love routine. It gives me stability. There is an outdoor gym nearby and I go there every other day to keep fit and it doesn’t cost a penny. I can’t do as much as I used to mind you. I’m no spring chicken, but for my age I’m not too bad, even though I am small in size. I’ve got used to being without family so that doesn’t bother me anymore. They cut me off years ago. I don’t have any real friends but I don’t mind. I’m used to spending long periods on my own and who needs friends when you have all the books you can read; a roof over your head; food on the table and money for the occasional drink. This is what keeps me level-headed. I haven’t needed therapy or medication in years. Mind my own business and stay out of trouble. That’s what keeps me going. At least it did until I met Henrietta. We met in the park while I was resting after a bit of exercise. She just sat next to me on the park bench and started talking. I had seen her in the park a few times but never thought I would get to know her. She looked like she was in her late teens although it’s hard to tell these days. Young enough to be my daughter, that’s for sure. She seemed genuine. At one point she even rested her hand on my knee. That’s a good sign, isn’t it? She had a lovely, warm smile. We met in the park regularly and she offered to cook for me. I’ve never had a woman cook for me since I was a kid. I invited her to my flat and shortly after entering, after having a good look around, she used the bathroom. When she came out, she looked different. A bit nervous. The doorbell rang which surprised me as I never have visitors. Before I could react, she opened my front door and a group of young guys came in. Henrietta obviously knew them quite well the way they greeted her. They all seemed so tall. What are kids eating these days to make them so big? They were not friendly like Henrietta. They didn’t even acknowledge me. After a brief time looking over the flat, they started moving furniture around. I was confused and stunned into silence. As I was watching them do this, I turned to ask Henrietta what was going on but she had disappeared. I finally asked one of them what was happening and he was very rude to me. He used bad language and told me to go to my room and stay there until he said I could come out. He then produced a gun from the small of his back and told me if I said anything, he would shoot me. I don’t like violence. I know what the effects can be. I did what he said and went to my room. When he called me, he informed me that they would allow me to continue to live there but the flat now belonged to them. They would use it for business and I was to stay in my room at all times until they had all left. He warned me what would happen if I told anyone or decided to inform the police and I believed him. He made me give him my spare set of keys. His friends were calling him Topper. Things changed. They were no longer simple. I was still allowed to go to work, the library, the park and have the occasional drink, but I had to depend on Topper to know when it was ok to be in the flat. Even on those occasions, I had to stay in my room. Lots of people kept ringing the doorbell and drugs were being sold and consumed. I noticed the familiar smells. It was mainly men that came, but sometimes there were girls too. Often, when I was in my room and Topper was there with his friends, I heard lots of screaming and moaning. Sex sounds. Really disgusting. My whole life was turned upside down as I had lost control. I had been in bad situations before but I thought those days were behind me. That’s when I started to get headaches. I knew from the distant past what that meant but I was no longer on medication. I needed a release. I started thinking about coping mechanisms I had used before when I finally realised what I needed to do. On my day off work, at a time I knew Topper and his friends would not be at the flat, I took my favourite knife from the kitchen and checked it was still razor sharp. I remembered years ago, after serving 22 years, telling the parole board I had learned my lesson and had genuine remorse for the lives I took. They acknowledged I was a different person and no longer a threat. I know how to cut people. I’m very good at it. I know exactly where and how to cut to make the end come quickly for them. I’ll go in hard and fast. I’ll wait for Topper and his friends to arrive. My head is starting to clear. I’m feeling better already. Tom Matthews is a London based writer of short screenplays and short stories. His work has been published in Literally Stories magazine. Wrote the screenplay for short films The Spice of Life and The Right Candidate. Has won screenwriting awards domestically and overseas, including festivals in Berlin, New York and Los Angeles. Soon Abigail would be coming up the street with her Husky. She’d be coming from the coffee shop. Not so long ago, when Abigail went for a coffee, she would stop and knock. She’d say Hey, did Rhonda want anything. Often, they’d gone together. Abigail had liked to walk arm-in-arm and talk about how to understand this year they had given to the mountains. Rhonda had come in June, Abigail in May, so she knew the ropes. This town was mostly a summer outpost, but it could be seen as a shrewd base camp, as skiing wasn’t far, and the rents beat the resorts. Abigail would have a latte, Rhonda a tea with bergamot. Sherpley would sit on the tiles with his head nearly to the level of the table, watching their conversation. The Sibe had a blue eye and a green eye and the white of his fur seemed blue like powder at first light. There was the question about the hike. They’d kicked it around the day before. Abigail had been ambivalent. She’d sounded put upon. She’d become critical of Rhonda’s moods. The problem with Rhonda, Abigail said, was that while she hailed from the suburbs of nowhere, she kept getting homesick. Rhonda went out to sit on the porch swing. Lights were coming on in the canyon. After all that awful wind, it was snowing again. The air smelled like cold mountain stones and grilled meat. In the fall, Rhonda painted the wooden slats of the swing red and yellow and orange because she’d been sad about her life here. Rhonda had intended to live an outrageously fun life before returning for a career. It’s not that it couldn’t be — hadn’t been — great. Abigail introduced her around and there’d been a backpacking trip early on with nearly a dozen others. But most everyone worked weird shifts. Coordinating a challenge. A lot of free days there was no one around. Sometimes it could be disheartening all alone on a trail out in the middle of nowhere. Abigail didn’t have to work as much. She’d become a reliable partner. And Abigail had been fun. She could make fixing a flat at tree line a big laugh where Rhonda would’ve been a big pain. But with fall came Donnie. He’d bought a place he’d gutted and hoped to renovate before things got busy with his work. He made good money, but the job required frequent trips out of state. Donnie was gentle and loving. He had sincere eyes. In those first days of Donnie, Rhonda imagined he would ask her about maybe a hike or ride. Then Abigail had looked after some task or other for him and suddenly they seemed on their way to becoming a thing. Now it was winter, and the narrow streets nestled in by these sheer rock walls a mess of snow and ice. All night and most of the morning the winds stormed the canyon, snapping at the conifers. Rhonda hadn’t slept well. There had been Abigail’s ambivalence. There had been what she said about Rhonda getting homesick too often. The worst part of it was that what Abigail had said made Rhonda even more sick for home and the life she used to know. Rhonda felt bewildered that wind could rush and whorl and crash like that, like it meant to scour the town from the canyon floor. Now the tiny crystals drifted down to settle gently as turning a page. Up the street came Abigail and Sherpley. Rhonda lived in a tiny unit on a short row of apartments built so close only the sidewalk separated the front steps from the berm of packed snow and ice left by the plows. “Hul-lew!” Rhonda said, wishing in the instant she hadn’t said it that way. She should have remained neutral. Passive. Calculating. Abigail looked surprised to see her. The Husky stared up at the snow falling. “It’s snowing!” Abigail said. “I know!” Rhonda said. A crow called from a rooftop. “I was just thinking about our hike tomorrow,” Rhonda said. “Should be epic now.” “Yeah,” Abigail said. “Not working out at my end.” Rhonda pressed her tongue to the roof of her mouth. Abigail shrugged. “I just found out,” she said. “Donnie’s back tomorrow.” Everything now always about Donnie and how Abigail might stay on a while longer. About how Abigail might just stay. Rhonda’s landlord had already asked whether she planned to renew. He’d be raising rents. Something flared in Rhonda. “What if I took Sherpley?” she said. “Sherpley,” Abigail said. Rhonda heard herself breathing. “I mean, yes of course,” Abigail said. She bent down to the Husky to scratch his ears. “You’re always welcome to give Sherpley a walk. Why, isn’t that right, Sherpley? Yes, he likes a good hike, don’t you, boy?” “But I’m not sure about tomorrow,” Abigail said, standing. “It’s just that, Donnie’s been away for days,” she said. She made a sad face. “We’ve been missing him. “You know how it is when your man’s away,” Abigail said. “We’ve been climbing the walls, haven’t we, Sherpley?” Rhonda stood. The swing lurched away to bounce against the backs of her legs. “Maybe another time,” she said. “Maybe Donnie can walk Sherpley.” Rhonda crossed her arms. She wished Abigail would go away. Abigail sank down to her heels and pulled the dog in close and he licked her lips. “Oh, now!” she said, delighted. Abigail stood. She smiled. Abigail and Sherpley walked up the street to her place, the dog prancing along beside her. They went inside and it was quiet again but for a car coming down the canyon road and — closer — the scrapes of someone shoveling. Rhonda sat on the hideously optimistic porch swing and wished she had never come here. Chuck Plunkett is a Denver-based writer who directs a journalism capstone at the University of Colorado Boulder. He has previously published stories in Cimarron Review and The Texas Review. He has an MFA from the University of Pittsburgh and is currently at work on a novel he likes to think of as a literary thriller. He's worked in several newsrooms, including The Denver Post, the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review and the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. That’s where my Dad was born: Whiskey Hill. It did perch on a hill, and local history has it that quite a bit of whiskey flowed down the hill into the valley below.

Then Prohibition came along, and the good town fathers (there were no women in government back then) changed the name to “Freedom”, as if somehow partaking of whiskey for so many years actually got you to Freedom. Maybe it did. Maybe it didn’t. The road to Whiskey Hill is still there. It is a narrow path, cutting off of Freedom Boulevard, hardly wide enough for one car. I can only imagine old Model T’s puffing their way up the hill to grab a keg of that stuff, whatever it was. If you didn’t know the road was there, odds are you would never see it behind the massive oak trees and overgrown poison oak. My father’s cousin was the last of the family to still live on Whiskey Hill. He lived right across the Presbyterian Church that spewed its bellowing out over the whole area on Sunday mornings. Everyone congregated at that Church, there wasn’t much else to do on Sunday mornings on Whiskey Hill. By the time my father’s family left, a new access road to Freedom had been built, and a freeway connected all of central California, with the town center relocated to the respectable valley below. I became the mostly respectable librarian in Freedom. One day at lunch I sat at a counter next to a young man who was wandering the West. His eyes truly glowed as he told me how he took the freeway exit labeled “Airport Blvd/ Freedom.” He didn’t find an airport – that was on a different road entirely – and although he found Freedom, Whiskey Hill would have eluded him but for the happenstance meeting of a mostly respectable friend. MaryAnn Shank spent much of her life in the shadow of Whiskey Hill. She wrote of her unexpected adventures in the Somali Peace Corps in the historical novel "Mystical Land of Myrrh". Her poetry has appeared in a number of publications, and she is presently engaged in bringing to life the story of another historical figure. Find her at http://mysticallandofmyrrh.com. “There are people who are unable to think," Abbot Corby said, "and there are those who can't feel. And there are people like you who can't do either. No matter how much you teach them, it won't do them any good.”

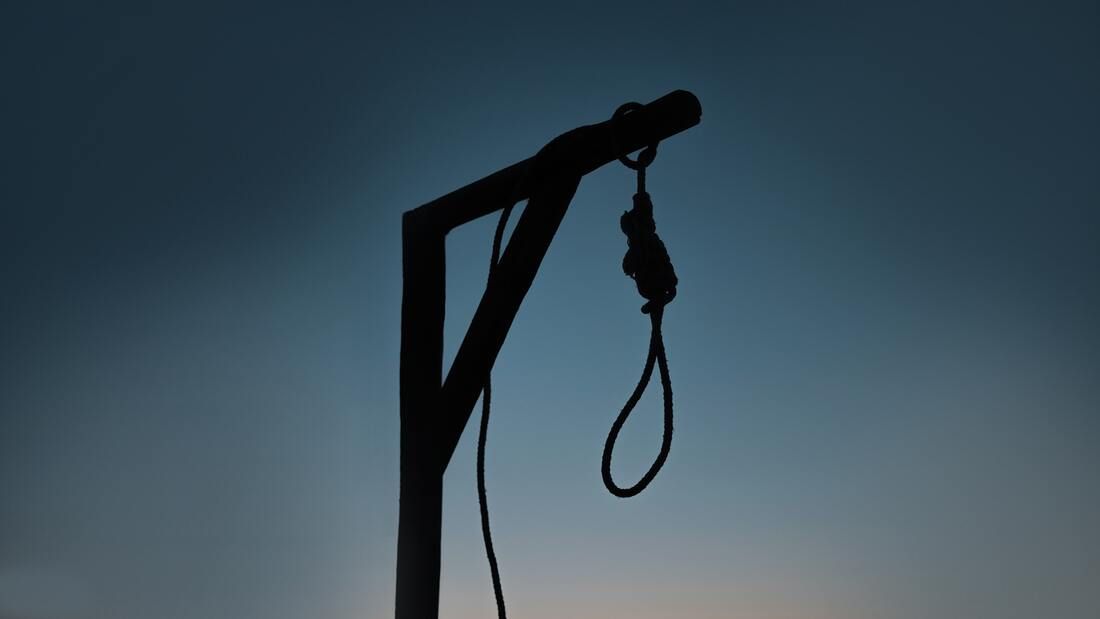

These were the exact words Abbot Corby said to his pupil, the unintelligent Charles, who ten years later would become King of the Franks and of the Lombards and Emperor of the West. Charles remembered well the lesson the abbot had given him, and one day, after drinking from a bottle of intoxicating power, he ordered his teacher brought to him and, when he was brought in, bound hand and foot and gagged, Charles asked, "Do you still consider me incapable of thinking and feeling? And when the abbot was silent because he could not speak, Charles ordered that the gag be taken out of the teacher's mouth. “Answer!” “I still think I was right," answered the teacher. The King of the Franks and Lombards and the Emperor of the West gave orders to tie the abbot to a pillar of shame. Townspeople were commanded to throw rotten eggs and other foodstuffs at the old man. Two days later a new order came out: Untie him from the pillar and bring him to the throne room. “Do you continue to think as you did before?” the old teacher was asked by the Emperor of the West, the Lord of the Francs and the Lombards. The teacher said nothing, just nodded faintly. The Emperor of the West, the Lord of the Francs and of the Lombards ordered to hang the abbot. When he was already standing at the gallows with a noose around his neck, the emperor went up the platform and again asked if the teacher had changed his mind about his former pupil. The old man answered with his eyes: No. The emperor nodded to the executioner and the executioner drew up the rope. The old teacher's body hung in the air. And it seemed that even his dead legs, swaying from side to side, were saying: "I was right." Nina Kossman is a poet, memoirist, playwright, editor, and artist. She has authored, edited, translated, or both edited and translated more than nine books in English and Russian. She was born in Moscow and currently lives in New York. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nina_Kossman We all entered through the front door hoping we would be received like we were at birth—cradled and held tight. We had hoped our entrance would be on white chariots with trumpets blaring and glorious music floating around us. But in reality, some of us entered in chariots of steel, others came in upright and holding onto a whittled stick, others laid on a mattress with railings and many were restrained in that same bedding, screaming, shouting and crying. Just like at birth.

We all thought we had been put in solitary confinement. Set aside. Removed from our homes. Removed. It was as if we had been misbehaved toddlers who needed a time out. Except nobody came to get us and our time was running out. We all had identical rooms—drab gray cinder block walls, one closet, one night stand, one lone single bed, and railings on the side that at first looked like an elongated crib. But this wasn't a nursery. Although, some of us still wet our pants and cried when we were being changed. We all were lonely. Sheila, in the room across the hall, was always talking to the man on the TV. She thought it was her son Michael. The man never answered her. Neither did her son Michael. We all didn't understand why we were here. Was it because we became strangers? A stranger to ourselves? A stranger to our family? Was it the multiple visits to the doctors? The ones who shot us with syringes of liquid hope. They gave us magic pills which only served to weigh us down like anchors. We all were on the bottom of the ocean with no life support or lifeguard to save us. Apparently, none of our family members knew how to swim. We all were confused. Holding onto favorite memories and sharing them repeatedly was comforting to us but not to the listener. There was a time when our parents would tickle us under our chin and we would giggle and giggle. Our parents continued to do this over and over again. We would laugh no matter how many times they did it. We all are still here, but no one is laughing. I began my writing career when I was an adult but now I think I am backsliding by reimagining fairytale stories in German. I love writing humorous Literary Fiction. Living in a log cabin on six wooded acres in Maryland, I found peace and solitude the perfect place to create. My first critique on my writing ability was in the 4th grade. My teacher wrote on my report card that I had a great imagination. That same teacher had me write "I will not talk in class" 100 times! Imagine that! Apparently, I had a lot to say even back then and a captive audience in the classroom to encourage me! Matthew had only signed up for the writing retreat because he’d been assured there would be no mentors, instructors, facilitators or teachers of any kind. Only fellow writers sharing their work, and only if the spirit moved them. After years of study, Matthew had concluded that writing was best shared but not taught. Either that, or he was unteachable. Probably the latter, in light of what a creative writing professor had once told him: “You are the most attentive student I’ve ever had. You listen closely to my advice, then do the exact opposite.” The problem had been some sort of cognitive dissonance—writing classes had laid out a roadmap for something that ought to be an ineffable, transcendent experience. Or maybe he’d just been too bullheaded to listen to teachers.

So now he was engaged in a last-ditch attempt to tap into the élan vital, that life force from which creativity sprang, if it existed at all. He’d rented a cabin at the retreat where he could write in peace, a musty little domicile that smelled of ancient books. But the writing retreat was turning out to be more like a retreat from writing. On day two, the blank page in his notebook somehow became even blanker. Here he was, amidst a burbling stream and rustling cottonwoods, or maybe it was a rustling stream and burbling cottonwoods, and the muse had only deigned to give him the middle finger. His presence was expected at the communal dinner every night, an opportunity for everyone to share their bon mots that had dropped like manna from heaven, but he hadn’t bothered out of embarrassment that he was manna-less. Maybe it was time to throw in the towel or the stylus or whatever it is one throws in when quitting the whole writing shtick. Finally, though, an idea came to him, born out of desperation: haiku. A compact form of expression to break the creative logjam. Quickly, he scribbled in his notebook: Rustling cottonwoods, A burbling stream. What the hell Does all of this mean? Famished after this burst of creative energy, he left the notebook on his picnic table and went inside to make lunch. As he assembled a pastrami sandwich, a dark shape whizzed by the kitchen window. He ran outside in time to spot a black bird swooping upward toward the tallest cottonwood. Too small for a raven, so it must be a crow. And the crow had left a calling card. White guano had scored a bullseye on his Basho-worthy masterpiece, now rendered unreadable. “Critic!” he yelled at the crow, now only a black speck at the top of the enormous tree. Well, he couldn’t take his soiled notebook to tonight’s dinner. He sat down, intending to copy the poem on another page in the notebook, but the crow, cawing its lungs out, stole his attention. When he finally pulled his gaze away, he wrote: The rushing stream lined By cottonwoods. The crows’ nest Crowns the tallest one. Okay, that didn’t entirely suck. Courtesy of a random act of crow. He took the poem to dinner that night, where he felt inadequate because other writers had finished entire stories or long poems. However, he was heartened when everyone complimented his efforts. A woman named Margaret, with intense blue eyes and gray hair pulled into a bun, attempted to explain how he could more fully use Basho’s techniques to awaken the senses. “I thought we were here to share our work,” Matthew replied, “not share our insights about Basho.” Margaret bowed her head. “Apologies. It seems like you’re searching for something, and I just wanted to help.” He felt terrible afterward and knew Margaret meant well, but his teacher defense shield had been activated. The next morning, he awoke to a raucous call, which sounded like the same damned crow. He heaved himself out of bed and stumbled to the picnic table. The breeze had the tang of coming rain, and dark clouds massed in the distance. The crow cawed even louder. On impulse, Matthew retrieved his notebook and opened it. He’d figured he was well and truly done with writing after the embarrassing display last night, but another haiku insisted that he write it down: The first morning light Touches the high nest. Silence Broken by the crow. “Thank you,” he called to the bird. He felt like an idiot, but the crow squawked back at him, then launched itself into the dawn. Matthew kept writing: The sky filled with sun And clouds. Yet it is the crow That consumes the eye. Not Basho exactly, but inspired nonetheless. After breakfast, he packed another pastrami sandwich along with the notebook and hiked along the stream. The riparian habitat gave way to an open, cultivated field, where his friend was waiting for him, perched on a cornstalk. He quickly wrote: Ebony crow lands On a cornstalk. Now he must Sway with the breezes. Everyone at dinner appreciated his offerings. Matthew apologized to Margaret, who patted his hand and said, “I think you’ve found what you’ve been looking for.” Had he? What was that, exactly? Later that night, the wind picked up, becoming a gale. The cabin shook and creaked, resulting in a sleepless night. The red light of dawn filled the bedroom as the wind finally died down. Something was missing. What? Then he had it: no morning wake-up call. He stepped outside to check the tallest cottonwood. No crow’s nest. At the base of the tree, he found the tattered remains of the nest. Three smashed eggs lay amid the twigs and leaves. He scanned the sky for the rest of the morning, desperate to see the crow, or at least hear a distant caw. Nothing. “Margaret,” he whispered, “you were right.” He opened the notebook and wrote very slowly this time: Without the crow, all Is silence. Good-bye, my friend. Good-bye, my teacher. John Christenson lives in Boulder, Colorado with his wife and a cat who is fond of penguins. His publications include short stories in the New Mexico Review, Flash Fiction Magazine, and several anthologies. A piece entitled “A Tree Grows in the Man Cave” was nominated for the Pushcart Prize. Hurley suspected the horseradish on his hot dogs had gone bad before he had the foil totally open. Something smelled fermented. In a weird way.

There were typically lines at flea market food stalls, so Hurley always brought his own, wrapped tight in aluminum foil he used at least twice before it went into his recycling. Leftover hot dogs with horseradish were a favorite. Hurley didn’t entirely trust his old nose, so he asked a younger passerby for an opinion. “Do these smell funky to you?” Hurley said, waving his partially unwrapped hot dogs under the surprised teenage boy’s nose. “Not James Brown funky, but like I might suffer for it later?” “James Brown?” the idiot kid replied blankly. Hurley sighed, then gave his lunch an easy underhanded toss into a nearby trash bin. Brian Beatty is the author of five poetry collections: Magpies and Crows; Borrowed Trouble; Dust and Stars: Miniatures; Brazil, Indiana: A Folk Poem; and Coyotes I Couldn’t See. Beatty’s writing has appeared in The American Journal of Poetry, Anti-Heroin Chic, Conduit, CutBank, Evergreen Review, Exquisite Corpse, Gigantic, Gulf Coast, Hobart, McSweeney’s, The Missouri Review, Monkeybicycle, The Quarterly, Rattle, Seventeen and Sycamore Review. In 2021 he released Hobo Radio, a spoken word album with original music by Charlie Parr. Beatty lives in Saint Paul, Minnesota. When the world realized the power of the girl, they began begging at her door. At first the line formed at sunrise and was gone by sunset. Before long it spread from city to city, until it circled the earth. The people built bridges and boats and left their families for years, just to find respite.

And when the girl realized the need of the world, she opened her arms wide to allow them in. She listened. When she heard about the heartbreak from the doe eyed lover, she felt the weight settle into the crook of her neck, with the weight of a kiss and the sting of a wasp. All their sorrow soaked into her body through the place on her chest where they rested their head. The burn of it poked at her: a twitch of muscle and a flick of pain. She ignored it, clinging to her guest because they needed her, and she needed them. When that same doe eyed lover left with a sunshine smile on their lips the girl buried that biting feeling inside. In they stepped, one by one, into the cottage that housed the girl determined to heal the world. The scent of tobacco and patchouli enveloped them as they entered her haven. They sat by her side and wept. And she wept too. Soon their tears were acid, leaving little trails of rashes and blisters on her skin. Their burdens got heavier, stiffer, like boulders stacked one by one on top of every part of her. Eventually she boarded the windows and lit candles because the daylight burned her eyes. When the feet of the visitors wore through the floorboards, she lined the walls and floors with the rest of her clothes, ensuring that everything visitors touched would be covered in softness. They would lay in the fabrics and wrap their fingers in her silk gowns, while she stroked their hair and sang to them. The day she stood to stretch, the weight of it all collapsed, causing her to stumble. Her ankle snapped, unable to carry the weight of everything the world left behind. She wrapped it with a scarf and pulled the bones tight into place, until she could feel them touching again. A few days later she removed the knitted fabric from her bruised and swollen skin, wrapped it around the neck of a farmer and kissed their forehead goodbye, wishing them luck in their harvest. Steadily, their troubles were crushing her. A banker whose loans had gone bad broke her ribs, the parent with the ghost child collapsed her lungs, and the artist with a knife to their neck snapped her spine. Each one leaving and swiftly forgetting the girl in the cottage with the rosewater lips. She became mangled as visitors off-loaded themselves onto her twisted body. They laughed as they left while she cried all their tears and felt all their sorrow. All too soon she could not move to hold them, her muscles, and joints all ripped at the seams. So, they lay on top of her to weep into her hair and hear her basket heartbeat. When the beat started to slow, drowning under pressure, they began taking small pieces of her before they left. A vial of her tears, a loose tooth slipped into the pocket, a toe bone whittled and strung into a necklace. They made sure to shoo away vultures that alighted on her roof and came tapping at the door. And when the priest came and realized there was no confessional for him there, he turned to close the door for good. From the darkness came a wheeze, a rise and fall of what could have been thigh or could have been chest. The remaining bits of fingers reached for the man and begged him to wait, a rotting stench leaked towards the door, sickly sweet like dying fruit. The pulp palm opened, revealing the girl's doldrum heart. “Bring them,” she cried. “Bring them one by one.” Kalie Pead is a queer poet, writer, and activist from Salt Lake City, Utah. Home for her, however, is somewhere between the red rocks of Moab and the wilds of Wyoming. She is currently an MFA Candidate in Poetry at the University of Notre Dame where she lives with her partner, their two cats, and their dog. In preparation for the search for Benny, Silver Lake was drained. For hours, aquamarine water spilled through the retaining dam as if a balloon had been punctured. Ever so gradually, the level of the half-mile-long pool receded, revealing a hidden ecosystem littered with dead fish, garbage, seaweed, and sundried vegetation along with a bevy of long-sunken canoes and kayaks.

My dad and Mr. Steinberg paced along the shoreline until late afternoon, when they were persuaded by Officer Hennigan, the leathery-faced, thick-necked local police chief, that it was futile to stay. “Will take until tomorrow,” Hennigan whispered in a gruff tone tinged with kindness. We climbed into Dad’s Chevy for the short drive back to the Palace Hotel, a popular summer lodging in the 1960s for escapees from the city. At Mr. Steinberg’s insistence, we dropped him off at the pub on Collins Street. As dawn broke the next day, I biked to the top of Langstrom Hill, which overlooked the lake. The early, piercing chill quickly faded and a rising sun illuminated white-uniformed state troopers and a growing crowd of spectators. With a pair of binoculars Mom used for bird watching, I scanned the depression that stretched like a caramel brown saucer between the trees crowding the surrounding slopes. Searching, to no avail, for my friend and his telltale green swim fins. By mid-morning, overcome by a sense of gloom, I lay back on the blinking grass and baked in the cleansing sunshine. Gradually, I slowed my breathing as my father had taught me to do whenever I felt upset and listened to the whoosh of the wind and rustling of leaves—sounds that had woven together and repeated since primeval times. Soon, the stench from the pit reached me. As I considered abandoning my watch, my father appeared and plopped down next to me. He wrapped an arm around my shoulder and pulled me to him. “I have bad news,” he whispered. Taking the time to compose himself, he continued, “They found Benny’s body, less than fifty yards from land.” I felt the need for tears but could not summon them up. Instead, I tore up a stretch of earth covered by grass and flung it. “Jake,” Dad said, “I’m so sorry. I know how close you two were.” I pictured myself discovering Benny’s stiff body and wiping mud from his carrot-red hair and freckled face. I imagined him with a radiant smile stretched across his face, the one he’d flashed when I last saw him. The remembrance both warmed me and made me gasp inside. “Dad, why did this happen?” “Benny wasn’t a good swimmer. He should have been wearing a life preserver.” “No, I mean, why do bad things like this happen?” “Oh, I see.” Dad’s lips came together in a mysterious grin. “That’s a question I'm not sure I can answer. I think you’ll need to figure it out yourself when you’re older.” With his arm draped around me, we sat together for the longest time, each passing minute inching me further from Benny and my connection to him. Further away from a time when all was good, or could be made so. When the moment was right, we rose and walked down the hill, our long shadows intersecting. Dad’s turquoise Impala was parked under the shade of a red oak tree. As we tossed my Schwinn two-speed into the back of the car and climbed in, a warbler’s trill greeted us. In its voice I heard Benny calling me. Seeking to comfort me. Dad studied my somber expression. “You okay? Wanna go get egg creams?” I shook my head. “It was my fault.” “Your fault?” “I was supposed to go swimming with Benny. But I overslept and he left without me.” Dad sighed deeply, making a sound like the release of air brakes. He leaned toward me and said, “You can’t blame yourself.” I nodded, then words rumbled out of my mouth. “Dad, do you think Benny is at peace?” “At peace? That’s an interesting question.” “I heard one of Mom’s friends say that Benny is with God and at peace.” “What do you think that means?” “That he’s not suffering, I guess.” “Yes, I do think he’s at peace. But what’s important to me at this moment is whether you’re at peace.” I shrugged. “I don’t know. I feel so sad, so I don’t think so.” Dad started the engine and we headed down the hill toward town, passing a doe and two yearlings picking their way along the side of the road. While stopped at the only light on Main Street, Dad grabbed a half-full pack of Pall Malls from his shirt pocket and tapped out a cigarette, which he lit expertly and jammed into his mouth. With no car behind us, we sat at the light for several cycles of red, orange, and green, mulling over what life had offered that day and might bring us next. Finally, Dad turned to me so that our eyes met. “What I learned at your age is that we all owe the world our death. What I later learned in the Navy during the war is that there’s always sadness and joy around us. They ebb and flow together. Where you are in them depends on the tide.” He kissed my temple. “It all depends on the tide.” Jeff Ingber is the author of books, short stories, and screenplays, for which he has won numerous awards. His first screenplay was the basis for the 2019 film “Crypto,” starring Kurt Russell. One of his novels, “Shattered Lives,” is being made into a documentary film by MacTavish Productions. His books have won numerous awards, including Elit, New Apple, New York Book Festival, Next Generation Indie, North Street, and Readers’ Favorite. His short stories have been published in various journals and magazines. You can learn more about his works at jeffingber.com. Jeff lives with his wife in Cranford, New Jersey. Jim, the writer, was jogging in an unfamiliar part of town when he had an inspiration. He’d brought no paper with him but his fanny pack held a pen. He eyed the businesses nearby and saw a sign over what looked like a sundry store, Everything $20.

He jogged in. “Paper?” he asked the slim, disinterested young fellow behind the narrow counter. The fellow gestured toward some pads and post-it notes. Jim grabbed a small package of the latter, stripped it of its cellophane and made a frantic scribble on the top note. “Ok,” Jim said, as if the clerk would share his enthusiasm. “How much?” “$20,” the clerk said. “Ha,” Jim answered. “Seriously, how much?” “Everything $20.” “No, look, I’ve got, what here…$3. Surely it’s not more than $3.” “$20,” the clerk reiterated. “I’m not paying $20 for a pack of post-it notes.” “You will or I’ll call the cops,” came the surly answer. “Right, you’ll call the cops over post-it notes. That I’d like to see.” Sam and Janet had just gotten married. It was early in the morning after the first night in their honeymoon city and its tony hotel. They were strolling, hand-in-hand. “I need a newspaper,” Sam said. “Here.” Janet pointed toward a store. There was a stack of newspapers on the counter. Sam picked one up. “Look at the headline,” Janet said. “It’s about that missing writer.” “I see,” Sam said. “How much?” he asked the clerk. “$20,” came back the reply. Oh, come on,” Sam said with some heat. COREY MESLER has been published in numerous anthologies and journals including Poetry, Gargoyle, Five Points, Good Poems American Places, and New Stories from the South. He has published over 20 books of fiction and poetry. His newest novel, The Diminishment of Charlie Cain, is from Livingston Press. He also wrote the screenplay for We Go On, which won The Memphis Film Prize in 2017. With his wife he runs Burke’s Book Store (est. 1875) in Memphis. |

Follow Us On Social MediaArchives

December 2023

Categories

All

Help support our literary journal...help us to support our writers.

|

Home Journal (Read More)

Copyright © 2021-2023 by The Whisky Blot & Shane Huey, LLC. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed