|

It was the worst of times and, yet, also the best of times. For, you see, a bad sickness had fallen upon all the world and all the little boys and girls everywhere had to stay at home. No school, no zoo, no parks, no visits with friends, and many couldn’t even visit Grandma and Grandpa’s house.

But little Levi was happy. He had his Mommy. He had his Daddy. He had his home. He had his toys and his books. And, at night, he had his new little friends, the Frogs. One night, as Mommy laid little Levi down to sleep, they heard a noise outside. “Ribbit!” “Ribbit!” Now, Levi didn’t even have to ask Mommy what was making the sound as he had already read about the Frogs in his story books. He knew immediately that this was a “Fwog.” From that night on, every day and every night, all day long and all night long, Levi asked Mommy and Daddy about the “Fwogs.” He even said “Fwogs” in his sleep! One night, after Mrs. Sun went down and Mr. Moon came up, it was time for little Levi to go to sleep. But he just couldn’t seem to fall asleep. All he could hear was the “Ribbit!” “Ribbit!” and his mind was only concerned about the Frogs. “Fwogs Daddy. Fwogs Mommy,” said little Levi. “Fwogs!” So Daddy asked little Levi if he wanted to go meet the Frogs and little Levi said “YES!…Fwogs!” Mommy and Daddy slipped a pair of shoes onto little Levi’s feet and out the front door they went to find the Frogs. Now little Levi, as luck would have it, lived right beside a small pond. A pond with rushes and lily pads and full of insects…everything that a Frog could ever want or need. And there was a well-worn path that wound about the pond, so Levi and Mommy and Daddy went for a walk around the pond. Mr. Moon shone his light brightly so that little Levi could see. Mr. Moon liked to look at his own reflection in the pond and so did all of the people and other creatures that lived by the pond. “Ribbit! Ribbit!” exclaimed some Frogs in the distance. Levi heard them too. “Fwogs!” he said. Along the path, Levi encountered a creature. “Fwog?” he asked. “No, I am a duck said the creature. Quack, quack.” “Duck” said Levi. And off little Levi went on down the trail. Shortly thereafter, Levi saw something else move in the darkness. “Snake!” said little Levi. Yes, that was Mr. Snake. But Mr. Snake crawled away before little Levi could even say “Hi.” Levi was not bothered by this though for he was determined to find the Frogs. Next, little Levi heard a noise in the trees. It was Mrs. Woodpecker. “Fwog?” asked little Levi. The Woodpecker replied, no, young man, I am a woodpecker…a bird…I dwell in the trees. I have seen no frogs this evening. I bid you a fond good eve.” And the woodpecker flew away into the night sky. About halfway around the pond, little Levi saw yet another creature that looked very much to him like a Frog. But it was very big and did not say “Ribbit” but, rather, croaked. “Fwog…big Fwog...” said Levi. “No, young sir, I am a toad!” “Toad,” said Levi. “Toad.” “Yes, a toad said Mr. Toad. We toads are distant cousins to the Frogs, but we are not Frogs and they are not toads.” And then, with one gigantic leap, Mr. Toad was gone. Little Levi looked and Mommy and Daddy, “Fwogs?” he asked. Mommy and Daddy looked at one another and were worried that little Levi might not meet the Frogs this night, for they were nearly full circle around the pond and nearing home. “Fwogs! Fwogs!” exclaimed Levi and the little family continued to walk until they could see the light on their patio. But the light drew nearer and nearer with no sign of any Frog. Mommy and Daddy looked at each other and then little Levi and said, “Well Levi, we didn’t find the Frogs tonight, but we will come back tomorrow…each night until you DO find a Frog.” Levi looked at Mommy and Daddy and said with a whimper, “Fwog...” Little Levi was sad. Mommy and Daddy felt bad. Soon, the little family was home and as Daddy went to unlock and open the door, and as Mommy picked up little Levi to walk inside, little Levi cried out, “Fwog! Fwog!” And sure enough, there sitting on the edge of the window by the front door, was a little Frog! Levi and the little Frog exchanged greetings and other pleasantries and, as it turns out, while little Levi was out looking for the Frog, the little Frog was out looking for little Levi. And now, each night before bed, little Levi and the little Frog take a walk around the pond together before bidding each other, "Goodnight." Carolina bit into her caramel apple. Or, at least, she tried to bite into it. She turned it around, hoping to find a weak point. She shrugged and tossed it into a garbage bin. Walking beside her, Devon hung his head.

“Look, I thought this would be fun,” he told her. “We can leave any time and go have a nice anniversary dinner.” “I told you—I’m happy here,” Carolina replied. “You don’t have to try so hard. We’ve done a fancy dinner every other year.” “Yeah, but ten years is a big milestone. I wanted it to be different…and perfect.” He casually touched his chest, ensuring that the jewelry box was still secure in his inner coat pocket. The carnival may be a bust, but the earrings would bring some redemption—he knew she had been looking at them online for months. “Come on. Let’s go on a ride,” she suggested. “Stop overthinking things and live in the moment.” Devon smiled but couldn’t shake the feeling that the carnival was a mistake. If anything, the feeling in his stomach after a ride on the tilt-a-whirl reinforced that thought. Glancing up, he could barely make out the words Starboard Amusements on the sign as they left the ride. Carolina spoke up as they passed a booth. “I remember that you were quite the pitcher back in the day. Why don’t you try to win a prize?” Devon laughed. “I haven’t held a baseball in years, but why not?” His skill clearly hadn’t vanished with time. He knocked down all six milk bottles on his first throw. “A fine throw,” said the woman running the booth. “Try again and see if you can win a bigger prize.” Another bullseye. “One final throw,” the woman said. “Can you win the biggest prize of them all?” Devon looked around the booth. “And what would that be?” The woman leaned closer. “First you throw. Then we talk.” Once again, all six bottles went flying. The woman’s eyes lit up. “At long last. Meet me at the back of the booth to claim your prize.” Devon’s eyes narrowed. “Why can’t you give it to me here? Too big to carry?” “This prize cannot be carried.” “Then what did I win?” asked Devon. The woman smiled and replied softly. “Happiness.” Carolina stepped in front of Devon. “I don’t know what you have planned, but I am not sending my husband back there with you.” “You misunderstand,” the woman replied. “Please, both of you come.” The back of the booth was a storage shed, packed with boxes of prizes. The only thing out of place was a red door, mounted on a frame but detached and leaning on the wall. The woman greeted them. “Eighteen years, I’ve been running this booth. You are the first to win the grand prize.” “Just hand it over, and we’ll get out of here,” said Carolina. “I told you that it can’t be carried. What I offer you is the happiest day of your life.” “And how are you going to make it so happy?” Devon asked suspiciously. “I will do nothing. The day will be just as you recall it.” Devon and Carolina looked at each other, then back at the woman. “I’m afraid I don’t understand,” he said. “How can you give us a day that already happened?” “First, we must address the ‘us.’ You have won a single prize. I offer this to only one of you. Pass through this door, and you will return to the happiest day of your life.” Devon walked over to the door. He stood it up and walked around it. “This door takes us back in time? Is this a joke?” He looked at Carolina for support but saw that her eyes were wide with excitement. “So, if this is real, you mean that we can’t both go back?” he asked. “One of you must go immediately. The other may play the game again.” Devon looked at Carolina, willing himself to believe for her sake. “You go,” he told her. “I’ll play until I win again.” Carolina walked quickly to the door. When she opened it, Devon saw the stacks of boxes that stood behind it. His shoulders sagged with disappointment, and he realized that he had been almost as excited as Carolina. But when she took a step through the door, no trace of her was left behind. “It’s real,” he mumbled. He turned to the woman. “It’s real!” “I would not deceive you. She has traveled back to the happiest day of her life.” “Well, come on. Let’s play again so I can go!” Once again, it took only three balls. When Devon opened the door, it looked just the same. However, having seen Carolina vanish gave him the confidence to step through as well, and the carnival vanished behind him. He had hardly dared to hope, but the green lawn of the university stood before him. The gazebo where he had proposed. He looked at his clothes—the spring coat gone, he was dressed for summer. He closed his eyes and replayed the scene in his mind, watching her walking toward him in the morning sun. The excitement in her eyes as she accepted the ring. He checked the time on his phone, smiling at the outdated technology. She should be here arriving any moment. Sitting down in the gazebo, he pulled the ring box out of his pocket and smiled. He might be the first person in history to experience his happiest moment twice. Again, he got lost in the memories. The harbor cruise in the afternoon. Dinner by the beach… He glanced at his phone again. 9:06. That couldn’t be right. They should be on their way to breakfast by now. The restaurant they had visited was across town, and they stopped seating breakfast customers at 9:30. A tired young man walked by. “Excuse me,” Devon called. “Do you know the time?” “My class ended at 9:00, so it must be just after that.” He checked his phone. “Yeah, 9:06.” Devon’s stomach tightened. Why wasn’t she coming? He got up and looked around. Someone was coming. He pulled out the ring box, eager to get the day back on track. It wasn’t her. “Sorry to bother you,” he asked the woman, “but is it May 14?” The woman stopped, puzzled by the question. “Yeah. Not too late to call your mom if you forgot Mother’s Day yesterday.” “No, I just…I mean…May 14, 2012?” She hesitated. “Yes.” She tilted her head, considering the situation. “Are you okay?” “Yeah, all good,” Devon replied. “All good.” As she walked away, Devon looked down at the box in his hand. How could this be the best day of his life if Carolina didn’t show up for the proposal? He opened the box and stared. Earrings. Not only no Carolina, but no ring. He scrolled through the contacts on his phone. She wasn’t listed. He called her number anyway. “Carolina? Sorry, you’ve got a wrong number,” a man’s deep voice replied. Mark could straighten this out. He had introduced them. “Devon! I’ve been out of town all weekend. Sorry to miss your poker night.” “No problem. Listen, I’m having a hard time getting hold of Carolina.” “North or South?” “My girlfriend. Carolina. Come on, I’m getting worried.” A pause. “You and Christie broke up last month. Did you forget about that…and her name?” “Never mind. I’ll call you later.” Clearly something strange was going on, but if he could just track her down… Her mom. A no-nonsense woman, she wouldn’t get involved in a prank like this. But even as he dialed, Devon already knew the answer…” “Carolina? You must have a wrong number.” “Mrs. Simchak? It’s Devon. I really need to speak to Carolina.” “This is Mrs. Simchak, but I don’t have a daughter. I’m sorry, but I don’t understand what’s happening. Who did you say you are?” He hung up without a word. Here he was, reliving the best day of his life, but without anything that had made it so good. There was only one possible explanation: the woman at the carnival had lied. If she got him into this mess, she must be the one to get him out of it. He remembered the sign: Starboard Amusements. If she had been with the carnival for 18 years, she must be traveling with them now. After a few guesses at the password, Devon was able to log in to his university computer account. The carnival was on its was to Kokomo, Indiana—only a few hours away. Unfortunately, as he only had a bus pass during his university days, getting there might be easier said than done. He thought he had left his hitchhiking days far behind him, but this was an emergency. It took three rides, but the third was heading straight for Kokomo. They wanted to talk nonstop, and Devon did what he could to at least sound polite. He got out where the carnival was setting up on the edge of town. He walked quickly between the booths and rides, ignoring staff who told him that they weren’t yet open to the public. At last, he found her. He had expected her to look ten years younger, but the woman looked exactly the same. “What happened? What happened to my wife?” The woman looked at him in confusion. “I’m sorry. I don’t think I know you…or your wife.” Of course. This was ten years before they had met. “I’m from the future, I guess. I knocked down all the milk bottles, and…” “And you won the opportunity to see behind the red door?” the woman finished. “Well, yeah. But you said it would be the happiest day of my life.” “I don’t choose the day. The door chooses. What made this day so happy?” “I proposed to my wife, but she isn’t here. Where is she?” The woman thought for a few seconds. “She should be here. The only other possibility is…” Devon waited for the sentence to finish, then prompted. “Is what? What is the other possibility?” “Did she also pass beyond the red door?” “Yes, she went first. We were going to meet and relive the day of our engagement.” The woman frowned, realizing the truth. “Did you discuss what day you would revisit?” “No, I guess not. Just the happiest day of our lives.” Silence. “What’s going on? What do you know? Why isn’t she here?” The woman hesitated, searching carefully for her words. “It would seem that…while today might be the happiest day of your life…” The truth dawned on Devon. “It wasn’t the happiest day of her life?” “I’m afraid not, my friend.” “So then, where is she?” A rueful smile. “I think the real question is ‘When is she?’” “What do you mean? She’s got to be somewhere?” “Alas, if she has entered another timeline, she exists only in the past or the future. She does not exist in the present.” “Okay, then, when is she?” “I am sorry, but the answer lies behind the red door. I have no way of knowing.” “Okay, then let’s play the bottle game.” “I’m sorry,” she frowned, “but the game only allows you to return to the happiest day of your life, not hers.” “So, there’s no way to find her?” “There is one. But you have only one chance.” “No problem. I’ve hit the bottles six times in a row.” “This one is more complicated. To visit someone else’s past, you must knock the bottles down from a distance of fifty feet. You have one attempt. Do you accept?” “Of course.” “Knowing that, if you miss, you will remain in this timeline forever?” “Yes, I guess so.” “Never reunited with your wife?” “Yes, yes. Just give me the balls.” “One ball. And here it is. I will set up the bottles, and then you will walk back until I tell you to stop.” Fifty feet had never seemed so far. In his days as a pitcher, it was sixty feet, six inches to home plate, but this seemed infinitely farther. “When you are ready, my friend.” Devon stared at the middle bottle on the bottom row. It would take a perfectly aimed shot, just off center, to knock them all down. Even the state championship seemed like an easy feat compared to this. The state championship, in which he had given up seven runs in the final inning. The day he had always considered the worst in his life…ironically, until he had won the privilege of reliving today. The carnival employees stopped to watch. He let the ball fly. Right on target. Five bottles crashed to the ground, but one still stood. He had knocked it to the back of the platform, but it remained upright. “I…I am sorry, my friend. The door must remain closed. I hope you will find happiness in this timeline.” “One more chance?” he begged. “I’ve got another dollar.” “I don’t make the rules. You had but one throw. I regret that I can do no more.” “Is there any other way to reach her timeline?” “I am sorry. I know of nothing aside from the red door.” The door. Devon ran around to the back of the booth. The door leaned against the wall, just as he remembered. He stood it up and pulled on the handle. Nothing. “It will not open. Many have tried, but the rules of the game can neither change nor be altered.” Devon stared at the door for a few seconds, a tear running down his cheek. He walked away without a word. The door may not open, but there must be another way. He would find it, even if it took… A crashing sound interrupted his thoughts. When he looked back, the platform was empty. “Did you just…” “I did nothing, my friend. You threw one ball, and no bottles remain on the platform. I will meet you at the red door.” Devon rushed to the back of the booth. “But you must have…” “I did nothing!” she shouted. “The bottles have fallen, and the door will open. Ask no more.” “But I don’t know what to do when I find her. Do I stay in that timeline? Can I bring her back?” “I can answer no more. You will know what to do. If you will pass through the door, it must be now, speaking her name as you enter.” And so he went, speaking clearly as he walked through. “Carolina Worth.” He saw nothing but boxes. He turned around and saw the woman, a sad frown on her face. “What happened? Why didn’t it work?” “I am sorry, but it seems that there is no Carolina Worth in her timeline. Perhaps she might have another name?” Of course. If she was in a timeline before they were married… “Carolina Simchak,” he said as he stepped through the door. He was seated on a boardwalk along what appeared to be an ocean. Glancing around, he saw her, standing with a group of friends. There could be no mistaking that smile. He rushed over to her. “Carolina?” Clearly puzzled, she replied, “Yes. I’m sorry…do I know you?” “It’s me. Devon.” She thought for a second. “Devon Huddy, from second grade?” “Devon Worth. You know…your….” He stopped, as the realization hit him. The best day of her life had been before they met. But how could he remember the red door at the fairground when she remembered nothing? “I’m sorry. I can’t place the name. How do I know you?” He looked around in desperation, wondering how to regain the love of a woman who didn’t even know him. Starboard Seafood Shack. The name rang a bell, but, as he examined the building, he noticed something even more important… “Sorry, I don’t think we’ve met. But…I was sent to give you a message.” “A message. From who?” “Your mother. Mrs. Simchak. She needs you to call.” Carolina’s face paled. “Is everything alright?” She pulled out her phone. “No!” “Why? What happened?” “No, I mean…she’s alright. Everything’s alright. But the cell reception is terrible here. You can use the phone at my restaurant.” “Your restaurant?” “Yes, the Starboard Seafood Shack,” Devon improvised. “A family business.” “And my mother called a seafood restaurant 800 miles from home to give me a message? Why didn’t she just call me directly?” “It must be that bad cell reception,” Devon answered quickly. “Our phone is right inside the restaurant, if you will follow me through this red door.” She gave him a skeptical look but followed. Sure enough, they found themselves back at the booth. Devon glanced down at his spring coat. So they had returned. “I’m sorry. What just happened?” Carolina asked. “You were reliving the best day of your life.” He looked her in the eyes. “A day that apparently didn’t involve me.” “Don’t act like that. I’ve had lots of great times with you.” “But better times without me?” “That’s not fair. I guess I just liked the freedom…” “Of life before we met?” “Well, they were easier times. Being an adult isn’t easy. You know that I don’t love my job, and…” “But even the early days of our relationship couldn’t compare to a visit to the coast?” “Those are my best friends.” “You’re my best friend. I was excited to relive the day that I proposed to you, but you…” “I’m sorry. That day was great, but…” “Forget it.” He turned to the woman at the booth. “When I traveled back, I remembered everything. How come she didn’t remember me in her timeline…or the door?” She frowned. “The heart chooses what to remember. Apparently, you wanted to hold on to everything, but…” “It’s fine. I get it.” Devon turned to Carolina, tossing her the ring box. “Happy anniversary, I guess.” He handed a dollar to the woman running the booth. Two minutes later, he opened the door, looked back without a word, and disappeared. Kevin Hogg teaches English and Law in British Columbia's Rocky Mountains. He holds a Master of Arts degree in English Literature from Carleton University. He writes in many genres, with his short stories leaning toward slipstream, and has spent four years writing a narrative nonfiction book about the summer of 1969. Outside of writing, he enjoys thistles, rosemary, and pistachio ice cream. His website is https://kevinhogg.ca and he can be found on Twitter at @kevinhogg23. Madan examined the game. His grandma, whose turn it was next, waited. He ran his left hand through his hair; She slammed a three of spades. They had a pre-assigned symbol for every suit and hair was for spades. The game was Mendicoat, a popular card game in those parts, and Madan’s team, comprising him and his grandmother, had gained an edge with the move.

“Darn it,” cried Janak. “You signaled at her, didn’t you, you cheater!” “Did you see me do that?” Madan responded, in a taunting calm manner. “Did you see me do that?" he then asked Kanchan, Janak’s partner for the game. “How will I! You people are experts at it. Grandmother especially!” Kanchan said. “May God take my eyes if I did it!” Their grandmother, reliably shocked, exclaimed, and the game continued. The sun was raging and they were seated on a charpoy under the shade of a huge Madras thorn tree in a shed next to their house; It was too hot and stuffy inside the house, a modest one-bedroom hall affair that was supposed to house more than fifteen people - matriarch’s four sons and their families - during the summer months. Madan went on to win the game, and consequently, the bet, terms of which stated Janak would take him to Karsanbhai if he lost. “I do not understand why you’re aiding Madan in such foolish endeavors,” Janak complained as he flung his cards. His grandmother told him she just wanted to win the game. She did not give two hoots about the bet. “Don’t blame me if something happens to him,” he said, “These city people come here with their fancy ideas. What do they know of the laws that govern life here!” “Come on, I just want to write an article on him. There’s no need to blow this out of proportion. Nothing will happen,” Madan said. “What do you know! Just want to write an article, he says. You have no idea what you’re dealing with. Think about it for a day or two.” “Today is Wednesday. You know he only performs the ritual on Wednesday. Next Wednesday I won’t be here.” “Let it be then. No need to go.” “But I won the bet.” “I don’t care about the bet.” “Okay, I will go alone then.” “Let’s see.” The game over, Janak and Kanchan shortly left to go to an aunt’s place, and Madan lay down, placing his head on his grandmother’s lap. “What is this new mischief? Nothing to do with your mother, I hope, may God bless her soul,” she said. “It’s work Grandma. I was talking to my boss about our village before coming here and I must have mentioned Karsanbhai. He was intrigued and asked me to do a piece on him.” “Why do you go around telling people about Karsanbhai? Do we look like samples to you Mumbai folks?” “No Grandma, it’s just what he does, nobody does nowadays. I don’t know of anybody else who claims to put people in touch with the dead.” “Don’t say ‘claim’. I know you will not believe it, with your education and all, but don’t assume you know everything just because you have a degree.” “I never said I don’t believe it. My job is only to report, not comment.” An atypical frown appeared on her face. “I don’t like this thing you’re doing. Writing about us as if we’re something to be read about and interpreted.” “Why are you clubbing the entire village together? I’m not writing about you.” “We’re all one people. Also, Janak is right. These are delicate matters. I hope you have thought it through." He turned his gaze to her face. She looked concerned. He saw no point in stretching it any further. “Maybe I won’t go.” She looked at him for a moment and then breaking into a mischievous smile, said, "I know you will go. You've taken after me. Once you decide, you don’t listen to anybody." "Nothing like that granny. It's a job, that's all." "What are you planning to do? Interview him? Will you be there when the ritual is performed? Be warned, it’s not for the faint-hearted!" He looked down, pinched his nose lightly, and said, "I will manage.” "On another note, I do hope you have taken after me. Your father isn’t the bravest of men when it comes to these things,” she said and laughed her grandmotherly laugh. Harsh beams of sunlight poured in through the branches above and met with his eyes. He covered his eyes with his right arm and turned to his side. His gaze fell on the closed window on the sidewall of the adjoining house. The house had stayed closed for as long as he could remember. He realized with some surprise that he did not know who lived in the house and why it was closed. He asked his grandma. "Oh, you don't know? The owner's son, a little boy at the time, drowned at the beach. His parents who were naturally in deep grief and shock left everything and moved to the city. This was more than fifteen years back and they still haven’t done anything about the house.” He looked at the window and shuddered. He wished he hadn’t asked. * Peacocks announced the arrival of the evening with their screams and people recommenced their outdoor activities. Madan went out the door and put on his left shoe. “This boy won’t listen. I have told him multiple times and in clearest terms that this is a bad idea. But who will pay heed to my advice!” Janak complained inside, to whoever was listening. Madan put on his right shoe. “Okay do whatever you want. But you will find yourself alone in this. I am not coming.” Madan set out. He looked about and realized not much had changed in the village. The houses, the pathways, the people looked the same as the last time he came here. The pace of life, of progress, was the same as the pace of vehicles that had to be driven cautiously in these narrow, unpaved lanes, lest they get scratched by a thorny branch. As he turned left out of the lane, not a hundred meters away came a bungalow on the left, the first house along the path, which was infamous throughout the village as a place of horror, a place to stay away from. There were various stories associated with the bungalow. The one that had stuck with Madan was of two teenage girls, twins, who had hung themselves. As he had grown older, he had forgotten the story but had not been able to get the picture out of his head - the sisters helping each other out probably, a serene look on their faces as life went out of them. Now, as he passed the bungalow, Janak’s phrase from earlier came to his mind, “Laws that govern life here.” What was that about? He had heard the phrase uttered by these people innumerable times since he was a little boy. Are these laws not the same everywhere? Was he a fool to walk into the unknown? Just at that moment, he felt a hand on his shoulder. He shrieked and rushed a couple of steps and then realized who it was. “Woah, what’s the matter?” Janak said. “No, nothing. You surprised me, that’s all.” “So gutsy! I fret to think what will happen to you when you see the ritual,” he said and spat. “I thought you weren’t coming.” “Might as well be there in case something goes wrong.” Ahead came the village chowk. They turned left and entered the lane with the Community Hall on the right and a compound with a huge tree, home to crying peacocks, on the left - an especially creepy place. As he walked on, he felt he walked further into darkness. All of a sudden, he wanted to return to the safety of the city. Something was not right. Hanging twins, drowning boy, communicating with the dead, the laws that govern this place, nothing seemed right. What was he thinking, getting into this mess, this darkness? He looked about to see if Janak was still there. He was. The world was running out of light though. The day was slowly wishing him goodbye. The night would see him now. * Karsanbhai stayed in a small room in a compound that also housed a temple. The large open area in the center was used for temple activities. It is here that Karsanbhai performed the ritual. As a boy, Madan had found it frightening yet inviting. Every Wednesday at ten in the night people would gather, some to witness and some to take part in the ritual. It was said nobody who came went back unsatisfied. Every participant believed they had communicated with the dead. It was pitch dark as Madan made his way into the compound. He was a little feverish, a result of the twenty-hour car ride he was sure, half of which was in the scorching heat. Karsanbhai wasn’t home. His apprentice met with them. “Say, Janak, how come you decided to call on him?” “This is my cousin Madan. He is from Mumbai and works there as a journalist. He has come for a week. He wants to write an article on Karsanbhai. Tonight, when the ritual is performed, he wants to observe it and interview Karsanbhai afterward, along with a few participants.” “I am sorry, but we cannot allow it. This is a sacred ritual and we believe it should not be publicized. An interview with Karsanbhai is out of the question I am afraid.” “That’s not why we’re here for. I want to participate in the ritual,” Madan said. “No no, this is not what we discussed. You are not participating. Why do you want to participate? You really think this is a game, don’t you? I will tell your father,” Janak protested. “I am participating. I want to talk to my recently deceased mother,” he said. “No no. Let’s go home. Let’s discuss this and come back. Let’s talk to your father. Let’s see what he says. You cannot do this.” But Madan had made up his mind. * Madan’s father had spent the evening walking the lanes of his childhood, with the people he had grown up with. Going back to his house now he was as satisfied as one is after a good, heavy meal. Entering the house, he asked his sister-in-law to make tea and went into the bedroom to change into a lungi. He noticed somebody sleeping on the bed with a couple of thick blankets on. He inched closer to ascertain the person's identity and realized it was Madan. He asked his sister-in-law about it. She said he was feeling feverish. “Happens to him when he's out in the sun for too long. Driving all the way from Mumbai was a bad idea," he said. He went inside and felt Madan's forehead. "Pretty bad, isn't it?" he said. "Give him a tablet after dinner.” Shortly Janak too rushed in and checked on Madan. "I had told him it was a bad idea," he said. "What are you talking about?" Madan's father said. "He wants to participate in the ritual. He wants to communicate with his mother. We went to see Karsanbhai." "What is this madness! You people should have stopped him." "I did discourage him. I told him he should stay away from all this. But he would not listen." Madan's father looked at Grandma questioningly. "I did not know," she said. His face changed all of a sudden. He sat down on the chair, closed his eyes, joined his hands, and mouthed a brief prayer. Madan started murmuring in his sleep. It seemed he was having a nightmare. * The nightmare Madan was at peace. He picked up a handful of sand and let it slip through his fingers. Ahead, the waves continued with their rhythmic ebb and flow. The sun looked forward to dipping into the sea. His family members were having a good time. The older ones sat at a distance from the seashore and looked at the sunset and the younger ones stood in front of the waves, shrieking with delight every time a wave crashed into them. He drifted into a vision from his childhood. He wore a bright red t-shirt, sky blue shorts, shades, and a yellow cap. He walked about without a care and kicked up sand every few steps. Having seen something in the sand a few steps ahead, he rushed toward it and crouched to examine the curious object. Then he looked back. Madan realized the boy looked nothing like his younger self and in fact, the boy was in front of him, actually there. It's the boy who drowned, he realized. Madan looked about. All his family members had vanished. A wave came and snatched the object out of the boy’s hand. He rushed to reclaim it. Madan stood up and sprinted toward the boy like a madman to save him. He ran and ran. And he realized he was running on the spot. He had not moved an inch forward. The boy reached the seashore. Madan ran on, helpless. He spotted something in the sky above the ocean; two girls, twins, preparing to hang themselves, the same serene look on their faces. He let out a series of screams. The waves came closer to him. The first wave crashed into him and he saw his deceased mother. The second wave crashed into him and he saw his father. The third wave crashed into him and submerged him and his hand emerged out of the water and he rose. Manish Bhanushali is based out of Navi Mumbai, India. His works have appeared in Livewire and Gulmohur Quarterly. Due to the overwhelming number of wonderful submissions, we were able to release a preliminary online issue for Spring 2022 and, as such, place the work of a number of our writers earlier than anticipated.

Thank you to all of the contributing writers and, as well, my fellow editors. Click here to read. Enjoy the issue. All is lost to me

Or rather, lost on me. Maples recoil from violence Of Moon; cold, harsh Now bathed in silent orange blood Teeming with silvered sweat I see mornings when Eagle thrice appeared Two times at my feet, once high above His message a subtle admonition To watch my feet; vipers are near. In the red marshes of sunrise I align myself with Wolf I am weary. I am tired. Settling down upon a rock I wait for warmth To soak into my bones H. Russell Smith, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation, lives in the Joplin, MO area. He is an avid Ham Radio Operator and bumbling supervillain. This story is dedicated to Andy. Professor Smith awoke to the most extraordinary feeling - as if she’d been married with children for twenty years. Yet nothing could be further from the truth: coupling with some sweaty, farting, hairy man had always been repulsive to her, such that she had long since banished any such thought from her mind. She gazed out at the neatly-trimmed lawn of Marlowe Court, which had stood in the centre of this Cambridge college for centuries. While her own tenure here amounted to just 25 years, she felt more kinship with its ancient granite and sandstone than she did with any of her lust-bucket fellow humans. After her customary boiled egg and slice of toast, consumed with a cup of Earl Grey to the soundtrack of Radio 3’s morning programming, she sallied forth to the Porter’s Lodge to check her post. *** Professor Smith hadn’t received anything other than rare books and journals in her cubby-hole for more than a decade, and even that rarely. These days, she went to the Porters’ Lodge for the banter with the all-male, all ex-forces Portering team. A particular favourite was Mr. MacGuinness, an ex-Beefeater and Guardsman who became an enthusiastic alcoholic following his military retirement. His red face and handlebar mustache made him look like a drunken sea mammal, while highly polished shoes and an earthy reek of tobacco confirmed his military history. “Good morning Professor Smith! It’s looking a bit empty in your hole, I’m afraid.” She stared at him, wondering whether he had just stated a fact or flirted with indecency. She allowed herself the beginnings of a smile before gathering her Incan poncho about her: “Good morning, Mr. MacGuinness. Perhaps you’d prefer it if I enlarged my post-bag?” “I don’t know about that, Professor. But a gentleman called for you and” – “A gentleman? Now there’s a rarity. Especially at eight AM.” “A Mr. Felipe Silvio, he said. He left a mobile phone number.” MacGuinness handed over a pink slip torn from an ancient message pad. Professor Smith looked at the handwriting and didn’t recognise it. But then, she didn’t get the chance to see a lot of handwriting that wasn’t six hundred years old: these days it was all text messages and whatnot. Even student essays were sent by email or posted on something called an “assessment hub” which she’d yet to access. “Did he say what he wanted?” “No, Professor. Er, something about a fragment from Padua.” “I see. Well, thank you. I shall give him a call.” Returning to her rooms, she put the kettle on for tea and tried to remember whether she had ever met this Felipe Silvio and what he might want. She set her last clean tea-cup down, pushing unwashed plates and cups up against a pile of essays she was avoiding marking. Then she picked up the receiver of her ancient Bakelite desk phone and dialled the number given to her by MacGuinness: “Pronto?” Professor Smith hesitated. Although she’d been reading and speaking Italian for thirty years, it was just – well, whenever she spoke to a modern she feared her immersion in the language and politics of the fourteenth century might manifest itself. “Sono Professore Smith”, she managed at last. “Ha chiamato per me?” “Yes!”, boomed Signor Silvio’s voice. “Professor Smith! I have the fragment. The fragment from the original Canto Twenty-Three of the Purgatorio what you wanted.” “I see”, Professor Smith mused, unsure whether Silvio had switched to English owing to her poor accent, or because he wanted to show off. “Well, where is it?” “I am here, qua, in Cambridge with the fragment. Please we can meet?” Any meeting, and especially an off-the-cuff meeting with a stranger, was anathema to Professor Smith. Her timetable was mapped out for the entire term in advance: undergraduates knew any request to rearrange a tutorial was met with tight-lipped disapproval. Colleagues had even observed her disquietude if dinner in hall should be served five minutes late. She checked the pocket diary lying on her desk. Other than a tutorial with a second-year rower of Olympian stupidity she’d scheduled for the end of the working day, that afternoon was empty. “Why don’t we meet for tea at three? Shall we say the Copper Kettle on Kings’ Parade?” “Perfetto”, Silvio confirmed. “Ci vediamo dopo, Professore!” She put down the phone and clenched her fists. This was most unusual. She couldn’t remember asking to see any original fragment, or indeed whether such a fragment existed. Sighing, she picked up the essay by the aforementioned, ungifted rower and spotted two errors and a grammatical infelicity in the first paragraph. As she ploughed her way through the boy’s confection of plagiarisms, stultifying regurgitations, mistakes, mis-quotes and naïveté, her head drooped against the hand that propped it up against the desk. Before long she was asleep. *** In her dream, Felipe Silvio was a raging bull chasing her through the streets of Cambridge. She was young again, racing across the market square on her undergraduate sit-up-and-beg bike with its wicker basket and heart-attack-inducing absence of brakes. However hard she pedalled, Silvio’s hooves beat harder against the cobbles and she felt his hot breath against her back. Eventually she could pedal no more and found herself succumbing to his masculine persuasive force, having ran out of puff on Jesus Green. The swans on the river craked as they witnessed her willing surrender to Felipe Silvio in the guise of a Taurean Lothario. Professor Smith awoke with a start to feel the sun on her face. Her head lay among the undergraduate essays, dirty cups and plates streaked with butter and egg yolk. Her Bakelite phone swam into view together with the shell from that morning’s egg. She glanced at the alarm clock on her desk. Ten to three – just minutes before she was due to meet Felipe Silvio. She rushed into the tiny bathroom in her set, pristine as it was (except the sink) through lack of use. She sniffed the hem of her jumper and realised she’d not changed her clothes for three days, or bathed. Never mind - nothing a dose of “Eau de Reine” couldn’t change. She duly doused herself in perfume, gave her teeth a perfunctory brush and looked in the mirror. She mussed her frizzy hair to the left and right, trying to cover up the grey. Then she carefully applied lipstick and headed for the Copper Kettle, remembering her keys and purse. As she strode across the quad her mind was fogged with sleep and her heart with Felipe Silvio: what he might be like, what he might say. She half-ran up Kings Parade, sniffing her wrist furtively in the worry that she’d overdone the perfume. Oh well, too late now. *** She recognised Silvio straight away. Where she’d pictured a broad-shouldered, mustachio’d Italian, she found instead cords and a round-necked sweater, thick glasses and nervous eyes that jumped around the room. She approached his table. “Mr Silvio?” “Professor Smith! An honour! I have read your monograph on the demotic and divine in Canto XXIII and I” – Elaine Smith blushed for the first time since her teenage years. Someone had read her work. “Oh, I – it’s nothing really. You’re most kind.” They ordered coffee and Silvio produced a thick cream envelope, leaning forward conspiratorially into the steam rising from their coffees. “What you are looking for is here”, he said. “I see.” Professor Smith was put out by Silvio’s business-like tone. “The thing is, I don’t remember ordering it. That said, I will admit to an interest in the original orthography of the Purgatorio.” She gave a little hoot of laughter, a nervous tic she had never rid herself of despite much self-admonishment whenever it occurred. Silvio tapped the side of his prominent nose conspiratorially and smiled. “It is gift. From a secret admirer. More I cannot say. Arrivederche, Professor Smith. Please allow me the honour of paying for your coffee.” Silvio rose from the table. They shook hands and Elaine felt the comfort of his warm, smooth, strong grip. Silvio pulled out his card to pay at the counter, saluting her as he left the café. After he left, Professor Smith reached into the envelope and found a scrap of taut, aged vellum. She pulled it out gingerly and her heart skipped a beat. Someone had just given her a textual variant from Canto XXIII. In twenty years of scholarship she had never heard of such a thing. Suddenly all the self-denial, the loneliness, the undergraduate essays devoid of residual brain-stem activity – it all seemed worthwhile. Of course, Felipe Silvio had been something of a disappointment. But she wasn’t finished with him yet, either. Returning to college, she tripped and fell against the sill of the ancient oak entrance. The initial stab of pain was replaced by a wave of regret in her heart, the same she’d felt earlier when she thought about the time she’d spent writing, marking, reading – all those activities she’d devoted herself to without anything else to focus on. Then she began to laugh and cry at once, softly at first, then with a ferocity that astounded her. Through her tears, she saw Mr. MacGuinness the Porter and one of his colleagues approaching. “Come along, Professor Smith. Let’s get you a bandage and some painkillers. Poor woman.” *** Elaine Silvio woke with a start on her sofa in Herefordshire. She’d had the strangest dream: she’d become an academic after graduation, rather than going into banking. Everything seemed different in her dream, and not in a good way – she dreamed herself to be sad, frustrated, middle-aged and unmarried without children, yet globally celebrated by a tiny coterie of scholars. In this other version of her life, her undergraduate interest in Dante became an all-consuming obsession that had eaten her womanhood. Elaine sat up on the overstuffed sofa and rubbed her face with her hands. Billy the Welsh Springer lay asleep on the carpet before her. He snuffled and turned over, inviting her to rub his tummy. It was Friday, she knew that much. She’d been up at four for a conference call with San Mateo about digital payments strategy. Accepting crypto. KYC, carry rules, AML and all those acronyms. So boring, so dull. But it paid for this house, and the kids’ education. Felipe’s passion for rare books didn’t pay their groceries, even if he was one of the most well-known antiquarians in Europe. He must have got the kids off to school while she was working. And she must have fallen asleep after lunch. She got up and stretched and looked out the window at the long expanse of the Welsh hills behind them, wondering what her life might have been like if she’d taken that PhD. Then she remembered it was her birthday, and she was due to meet Felipe and the kids in the centre of Hereford. For once, Felipe had agreed not to go to an Italian restaurant. The kids wanted Chinese – and they’d won. *** When Professor Smith awoke, she lay alone in bed. The fragment Felipe Silvio gave her sat on top of the undergraduate essays, dirty cups and egg-smeared plates on her desk. Wincing in pain as she stood up, she hobbled over to her desk and peered intently at the fragment. She could hardly make out the words, they were so faint and hastily-scribbled. But there they were, clear as day, written above the accepted version. Where the Dante we knew had written: … « ché ’l tempo che n’è imposto più utilmente compartir si vuole » Professor Smith could see words that didn’t mean, “the time of our life/can be used more fruitfully than this,” but instead – “time is our life, and time/is for none to dictate its use.” She looked at the text four times from different angles. She turned the scrap over and tried to read it through the fading afternoon sun. She was certain: it was genuine. A real discovery, the first in Dante scholarship for centuries. *** Elaine Silvio entered Hang-Sui House looking left and right for her husband. She’d dressed simply in a black trouser suit and a blue silk shirt, the same clothes she’d worn for work that day. But she’d refreshed her makeup, brushed her hair and added a spritz of “Eau de Reine,” the perfume Felipe always said reminded him of when they met. She wanted to make an effort for their celebration after a rushed journey to the restaurant from their home, caught in the traffic she’d forgotten existed since she started to work from home. The kids texted to say they’d be late – something about Anthony having to wait for Bea to finish hockey. At least it meant she’d have some time alone with Felipe. When she reached their table, she kissed Felipe, his brown eyes smiling. She accepted a menu from the waiter and ordered a large glass of sauvignon blanc, scanning the menu. When her wine arrived, Felipe raised his glass of red in a toast: “Salute, carissima. My gift to you.” Felipe handed her an envelope. Inside there was another envelope containing a scrap of old parchment about two inches wide and three inches long. Elaine could make out some squiggly handwriting on it, thick with crossings-out and editing. “What is it?” “It is a lost verse from Dante’s Purgatorio. I found it in an antiquarian’s in Padua and persuaded them it was a medieval shopping list of minimal value. The words tell us no-one has the right to dictate how we live our lives. I know how much you loved his work, so…” She kissed him again and turned the scrap of parchment over in her hands. She could hardly remember her Italian at this distance, let alone read such ancient handwriting. “Grazie, darling,” she managed at last. The children arrived in a flurry of schoolbags, teen-speak and undried hair. The waiter brought prawn crackers and food was ordered. Laughter and chopsticks and toasts followed. Pushing out into the gathering dark two hours later, Elaine waited with the children while Felipe went to fetch the car. Not listening to the kids griping at each other about some perceived slight visited on Bea by a girl at school, Elaine’s eye turned to the display window of a bookshop on the high street behind them. She caught sight of a pile of books in the window with a poster of the book’s title behind, and clutched for her son’s arm as she fainted: Dirt and the Divine in Dante by Professor E.S.R. Smith Professor of Medieval Italian Literature and Culture University of Cambridge A Scotsman by birth and profession (though only an occasional whisky-sipper), J.W. Wood's short fiction has appeared in the US (Black Cat Mystery Magazine, Carve, Expat Press), Canada, the UK (Crimeucopia, Idle Ink, others) and other markets around the world. He has worked as a literary reviewer and journalist and is the author of five books of poems and a pseudonymous thriller, all published in the UK over the last fifteen years. Jeffrey Dickerson spins the Tahoe’s steering wheel and turns off the highway onto an overgrown and barely visible dirt track. I’m surprised I can still find this place after more than 50 years, he thinks. The SUV moves slowly across a meadow, flattening the road’s vegetation as it passes, and continues into the pine forest. Under the dense canopy, no sunlight reaches the ground and a somnolent gloom envelops the vehicle and Jeff.

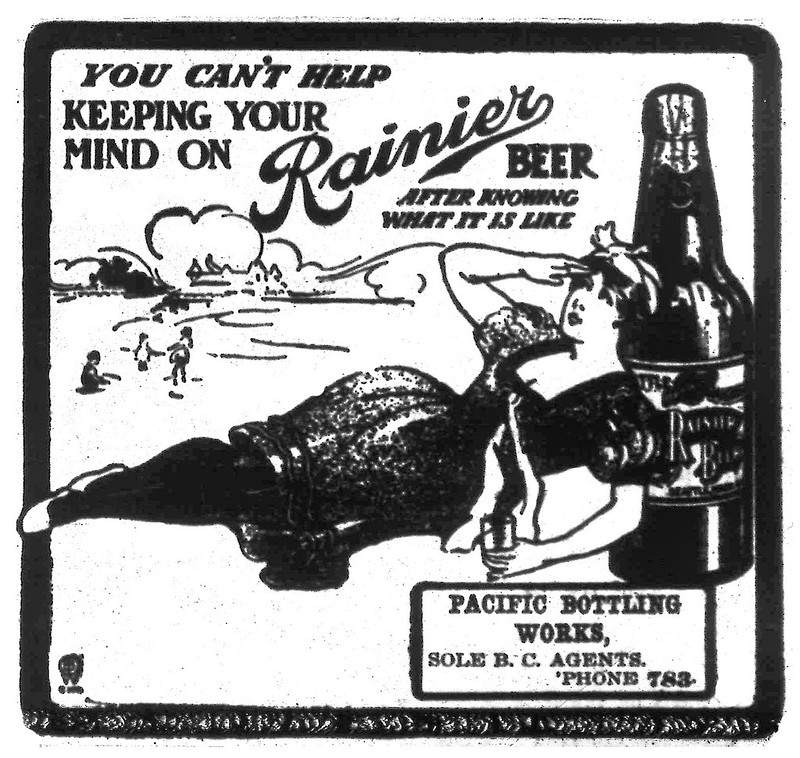

Geez, we used to do this at midnight, drunk on booze swiped from my stepdad’s liquor cabinet. The grasses and undergrowth disappear and he follows the eroded Jeep trail past trees that have doubled in diameter since his last visit to the lake. At a clearing, he pulls up and kills the engine. A strong wind down from Canada whistles through the pines, cooled by snows off the Cascades. A thick blanket of needles covers the ground, free now of the beer cans, candy wrappers, used rubbers, and assorted trash that Jeff remembers from his youth. I guess nobody comes here to make out anymore. But then why would they after the mills closed and the town emptied. He pulls on a down jacket and wool cap, wraps a scarf around his neck and sets out, following the memory of a trail that has all but disappeared. Jesus, if I get turned around out here, nobody will ever find me. But in a few minutes the wind freshens and he sees sunlight shining off the lake. He strides out of the forest onto its stony shoreline. The surrounding mountains haven’t changed, snowcapped, ever watching. He sits on a boulder and breathes in the fresh citrusy-smelling air, so much different than the bluish-white haze along LA’s freeways. But the cold seeps into his bones and his arthritis screams for relief. He pops a Norco and washes it down with a shot of Jack from his pocket flask. His body gives a huge shudder, then settles. Jeff waits for the pain drugs to hit before pushing himself up and moving off down the shoreline, slipping on the stones and swearing. At a particular spot, a rock formation juts into the lake. As teens, he and his buddies Terry and Leo ditched their clothes, picked their way to its end, and dove into the crystal clear water. The cold felt great on hot summer days. But this autumn day, Jeff turns away from the lake and into the forest, mumbling to himself, counting steps. At 25, he looks around. Two gigantic ponderosas stand guard over a mound of granite. At the rock’s base, he lowers himself to his knees. He scratches away the carpet of needles, withdraws a garden trowel from inside his jacket and begins to dig, carefully. In a few minutes he hits something. Digging now with his trembling hands he uncovers and withdraws a mason jar, its lid corroded but intact. The jar’s glass has frosted over. He tries removing the top but it won’t budge. In exasperation, he taps it against the rock. With a tinkle of glass the jar shatters. Jeff reaches forward and picks up two cards, one a Washington State driver’s license, the other a tattered Social Security card. He stares at the license. Jeff’s young image stares back, his somber face next to the name Roger Stokley. *** Roger smeared Sea & Ski on his arms and face, and watched Terry and Leo repeatedly plunge from the rock jetty into the lake. He clasped a Rainier Ale between his thighs; the cold can felt great in the August heat. Leo had swiped a couple six-packs from his father’s grocery store. The friends had vowed to spend the last weekend home after high school graduation getting drunk on whatever they could scrounge. The two friends joined him on the stony shore. “You better not have guzzled all the beer,” Terry chided. Roger grinned. “Nah. I’ve left ya a can or two.” “Where the hell did the church key go?” Leo complained. “Relax, it’s in the cooler.” Shivering, the two swimmers dried off, sat next to Roger sipping their beers, and stared at the lake, its waters glassy calm. “So, you all set for Nebraska?” Roger asked Terry. “Yeah, I guess. I’m on the bus Monday. Classes start the next week.” “Can’t believe you’re goin’ to U of N,” Leo said. “I think they’ve got three trees in the whole damn state.” “Hey, I gotta go where they accept me. That’s the deal. And do you think Montana Tech is that much better?” Leo grinned. “At least they’ve got mountains and trees.” “What about you?” Leo asked Roger. “Got it figured out? You need to get into school or they’ll draft your ass and send ya to Viet-fucking-nam.” “Yeah, well I’ve had enough of school. Don’t like it much.” “But, if you don’t at least enroll somewhere you’ll—” “I get it, I get it. I’ll figure it out.” But Roger didn’t have a clue about what to do. And his stepdad wanted him out of the house, to make way for a new girlfriend so they could fuck all day long without Roger snooping around. His stepdad didn’t care what Roger did, just wanted him gone. An uncomfortable silence settled between the friends. Roger realized that this could be the last time he and his pals hung out. The afternoon wore on. Their clutter of empty beer cans grew. They dozed in the golden light, faces burnt a wild cherry red. Groggy, with a headache coming on, Roger woke. “Gotta pee,” he muttered, pulled on his shirt and pants, and stumbled into the forest. He stopped at a mound of rock framed by two young pines, unzipped and wet the stone with four beers worth of piss. As he finished, he noticed something strange. A pile of neatly folded guys’s clothing and a pair of shoes rested near the top of the rock. He scanned the forest but failed to spot any naked guy wandering around. Maybe he’s swimming in the lake? But we’ve been here all day and have had the place to ourselves. Pine needles covered the shoes and a long-sleeved sport shirt that topped the pile. Totally weird. Whoever left this stuff must have split days ago. Roger carefully slid the creased slacks loose and checked the pockets. No car keys. How the hell did he get here . . . or leave? The buttoned-shut back pocket held a wallet. Roger sat on the ground, his heart racing, and looked through each compartment. The wallet held 96 dollars in small bills. A driver’s license belonged to Jeffrey R. Dickerson, 21, of Tacoma, Washington. Roger stared at the license and at the photo image. What was this guy from Tacoma doing around here? Jeff was close to Roger’s height and weight with the same color eyes. But Jeff had a thick walrus mustache. Roger continued to dig through the wallet. He found a Selective Service Notice of Classification card that showed IV-F. A grin split Roger’s face. Not only does this guy look a little like me, but he’s old enough to buy booze and won’t get drafted. An escape plan formed in Roger’s mind: I’ll become this guy and lamb on out of here. Go south to Frisco and get lost in the hippie scene, that Summer of Love shit. Roger’s mind filled with all the details that had to be worked out. But at least now he had an idea, one that just might work. He took the wallet and slid it into his pocket, scraped the dirt away from the base of the rock and buried the clothes. When Roger returned to the shoreline, Terry looked at him and laughed. “That was some pee. What were you doin’ in there, jerking off?” “Nah,” Leo cracked, “he wouldn’t take that long.” “Come on, fools,” Roger said. “We gotta go.” The trio checked the beach to make sure they hadn’t left anything behind, then hustled down the well-worn path to the clearing and piled into Leo’s Ford Econoline van. On the way back to town they didn’t say much, sleepy from the beer and not really knowing how to handle their goodbyes. Finally, Roger broke the ice. “Hey Leo, you takin’ this piece-of-shit van to Montana?” “Nah, my Pop needs it for the grocery.” The silence returned and when Leo pulled up in front of a ramshackle clapboard house, Terry bolted from the van, rubbing his eyes. “Give ’em hell in Nebraska,” Leo called after his retreating friend. Terry waved his hand but didn’t turn around. He disappeared inside the house. When Leo got to Roger’s singlewide trailer, he turned the engine off and swung around to face him. “Look, I don’t leave for Montana for a week. If you need help figuring shit out let me know. I know you’re freaked out about it. I would be too.” “Yeah, thanks. But I’m workin’ on an idea.” “So what is it?” “It’s better that I keep it to myself. But don’t worry, I’ll be all right.” “Cool. Glad to hear you got somethin’ goin’.” “So, I’ll see ya, man. And say hi to your Pop for me.” “Yeah, Roger, sure. Stop by the market anytime. I’m sure he’d like to shoot the bull with you.” It took Roger over a month to grow a walrus mustache. He trimmed it to look just like Jeff Dickerson’s. One Sunday in September, when his stepfather had taken his girlfriend out for a drive, Jeff gassed up his beat-to-hell Volkswagen Bug. He stowed his guitar and a battered suitcase full of essentials and headed to the lake for what he planned to be the last time. Hustling into the woods he removed his driver’s license and Social Security card, placed them in a Mason jar, and buried them next to Jeff’s decaying clothes. If anyone ever finds this stuff, they’ll think it’s me that disappeared. At that moment, Roger Stokley felt he’d become Jeff Dickerson. He ran to his car and raced back to the two-lane highway that led south toward the Interstate. After a pedal-to-the-metal dash across Oregon, he motored into California, pushing even more frantically southward, toward the City by the Bay where the hippies and other remnants of the Summer of Love took him in. *** Groaning, Jeff Dickerson stands and slips his old driver’s license and Social Security card into his shirt pocket. He kicks dirt over the shattered Mason jar and walks back toward the lake. At the shoreline he stops to stare at the high storm clouds rolling south. It might rain and snow that night. On the far shore, brightly colored kayaks and canoes are stacked in racks on a dock that serves a lakeside resort. The huge complex looks closed for the off-season. This place must be a circus during the summer. A gust of frigid wind hits and Jeff moves off, finds the trailhead and returns to the clearing and his welcoming Tahoe. Inside, with the heater blowing full, he stares once again at his old driver’s license picture. Well, I’ve done it. But what was I expecting? Some sort of magical return to my former self? So stupid. Everybody I knew is dead or close to it, including the whole damn town. Back on the State Highway, he approaches his hometown. The Internet pictures he studied showed a place just a few years away from becoming a ghost. Now, driving down the main street, the forest has already reclaimed some of the stores and houses. The last mill shed at the north end lies broken, its ridge rafter sagging, with berry vines claiming the rest. The hotel leans ominously with graying particle boards nailed over its doors and windows. Jeff cruises the back streets, dodging monster holes that pockmark the crumbling asphalt. Terry’s house has disappeared under a mound of creepers. A similar mound occupies his stepdad’s property. One end of the ancient trailer still feels sunlight, its roof gone with fire burns licking up from glassless windows. But Leo’s place stands in good repair, a satellite dish on its roof and a propane tank in the side yard. On the corner of the main street, close to the highway, stands Owens Grocery. A couple neon beer signs glow in its small-paned windows. The single Gulf Oil gas pump has been replaced with a modern Chevron pump. Could Leo’s family still run this place? God I’m thirsty . . . could use a cold one. Jeff parks out front, climbs onto the wooden porch and enters the store. A bell rings over the door. He shuffles across the worn wooden floorboards to the counter. A middle-aged man sits staring into a smart phone, grinning. He looks up and smiles. “How can I help you this afternoon?” “You guys sell Rainier Beer?” “Sorry, mister. We have Bud, Coors, Miller, Moose Head and a bunch of boutique beers. But no Rainier.” An old man slumped in a corner chair next to the Franklin stove mutters, “We haven’t sold that swill since the seventies. The brewery got bought up and moved to LA.” Jeff sighs. “That too bad. Me and my friends used to drink that stuff out at the lake.” The old man unfolds himself from his chair and hobbles toward him, his right hand clutching a cane, the left hand and arm hanging limply by his side. He moves in close, removes a filthy baseball cap and stares up into Jeff’s face. “Well I’ll be damned. Roger Stokley, right?” For a moment Jeff stands frozen in place. He hasn’t been called Roger since he fled after high school. He doesn’t know whether he wants to reveal such a long-held secret. Can they put him in jail for impersonating someone else; for prematurely drawing Social Security under a false name; for failing to notify the police when he found the wallet? And his children, what would they think? Would it get back to them and his ex? And does he really want to open that trap door into his past? The eyes that stare into his look young. He lets out a breath and grins. “Is that you, Leo?” “Who else would hang around Owens Market? Come on, pull up a chair and let’s talk. Jesus, I never thought I’d see your sorry ass again.” “Yeah, us Stokleys are tough, real survivors.” The old men sit next to the radiating stove and sip beer brought to them by Leo’s son, David. “Dave keeps this place goin’,” Leo says, beaming. “He makes his money as a software designer out of our family’s old place. His kids are in college and his wife and I get along great. Got my own room and shitter. What more can a man ask for?” “Yeah, I’ve driven by your place. It’s the only one that looks occupied. What the hell happened here?” “What do you mean? We saw it start while we were in high school. The mills closed and folks moved out . . . some just walked away from their homes.” “But you’re still here.” Leo flashes a lopsided grin. “Near the end of my second year at Montana Tech Pop had a stroke; must be hereditary. I came back to help Mom run the store and take care of Dad. Both of them have been gone for decades. But I never left.” “How do you do it?” Jeff/Roger asks. “The off season is tough. But they’ve subdivided a big patch of forest a few miles easta here and built all-season homes. Enough of the folks overwinter and we’re the only store out here.” “Yeah but . . .” Leo continues. “They’ve built a big resort on the lake that operates from early spring through Halloween. I get lots of business from the tourists and the resort itself. And they put in a huge KOA back in the woods from the lake. Folks stay there for weeks and need supplies.” “But . . . but you were gonna be a mining engineer, travel the world and make big bucks as a consultant. And you have a wife?” “Had. Elaine couldn’t handle the isolation of the great north woods,” Leo says, laughing, and gulps his beer. “We divorced when David was in high school. Haven’t heard from her in years. She’s down near The Dalles somewhere. Either that or dead.” The heat from the stove and the beer calms Jeff/Roger and he slumps in his chair, relaxing for the first time on his trip up from LA. “So . . . I drove by Terry’s house. Gone. What happened?” “Good ole Terry lasted less than a year in Nebraska. He quit school and joined the Marines. He’s fertilizing some rice paddy in the Mekong Delta. His folks moved away, just left the house one night with all the lights on and the front door wide open.” David replaces their empties with fresh cold ones. A comfortable silence grows between the two men. The fine tremor that has shaken Jeff/Roger during his long trek north has calmed. Finally, Leo speaks. “Aren’t ya gonna ask about your stepdad?” “I’m curious, but I don’t really care. There was never any love lost between us.” “Yeah, I get that. He lived in that funky trailer with various women for a few years after you left. Then a pissed-off girlfriend doused him in booze and lit him up. You probably noticed the burn scars on the place. He died shortly after that. Your place and most of the others were taken over by the County for delinquent taxes. A while back they held an auction trying to sell ’em, but got no takers.” “Huh,” Jeff/Roger mutters. “So . . . I’ve been blabbering on this whole time. What the hell happened to you? It’s pushin’ sixty years since you left.” Jeff/Roger sucks in a deep breath. Should I tell him the truth? Who can it hurt now? Everybody’s gone or dead. He takes out his old driver’s license and hands it to Leo. “You kept your old license? Jesus, ya look like some wise-ass hippie punk.” “Yeah, I suppose I was.” Jeff/Roger removes his current license from his wallet and hands it to Leo. “What’s this? Who the hell is Jeff Dickerson?” “It’s me, man. It’s me.” Leo stares at him wide-eyed. “What the fuck you talkin’ about? You’re Roger Stokes. We used to go to the lake and mess around, drink Rainier.” “Yes, I remember,” Jeff/Roger says. “That last time at the lake, I found a guy’s wallet back in the woods. Stole it, stole his identity and split to California, talked them into giving me a driver’s license.” “Holy hell, you’ve lived someone else’s life all this time?” “No. I’ve lived my own life . . . just under a different name. And it paid off. The guy was three years older than me and IV-F. So I could buy booze, avoid the draft, and decades later sign up for Social Security three years early.” “And the guy never turned up?” “Beats me, I’ve never looked. My bet is that he drowned in the lake and they never found him.” “Why do you say that?” Leo asks. “Along with his wallet I found his clothes. Could have been a suicide. The guy was from Tacoma.” Leo’s eyes grew large. “Ya know, about fifteen years after you left, a big storm churned up the lake. Some hikers found human bones along the shoreline. Never did identify who they belonged to.” Jeff/Roger grins. “Well, by then I was livin’ in LA with a wife and two kids, teaching math to high school students.” Leo’s mouth dropped open. “You, a teacher? You hated school.” “Yeah, well forty years of that was enough. My wife left me and my kids are scattered. I guess I’m searching for a place to land.” “Maybe an old place?” Leo grins. “Maybe.” “So . . . so what should I call you?” “Call me . . . Roger. I’ll claim it’s my middle name.” “Cool.” “But . . . I’ve gotta go back to LA. Gotta take care of business, ya know.” Leo nods. “Will we see ya up this way again?” “When you start stockin’ Rainier Beer, I’ll consider it.” “So you’re not coming back?” “I’m . . . I’m Jeff Dickerson of Pasadena, California.” “Yeah . . . Jeff. Thanks for stopping by and . . . I’ll catch you later.” Seems that Leo has gotten better over time with goodbyes. Jeff pushes through the market’s front door. The bell tinkles. Back in the Tahoe he heads south, retracing his 1967 flight. After visiting his past, he knows that’s not where he belongs and that Thomas Wolfe is right. Terry Sanville lives in San Luis Obispo, California with his artist-poet wife (his in-house editor) and two plump cats (his in-house critics). He writes full time, producing short stories, essays, and novels. His short stories have been accepted more than 490 times by journals, magazines, and anthologies including The Potomac Review, The Bryant Literary Review, and Shenandoah. He was nominated twice for Pushcart Prizes and once for inclusion in Best of the Net anthology. Terry is a retired urban planner and an accomplished jazz and blues guitarist – who once played with a symphony orchestra backing up jazz legend George Shearing. Paunchy from being fêted at innumerable Michelin star restaurants, Vice President of International Harry O’Toole greeted me with a salesman’s handshake and a predator’s smile that underscored a bulbous, burst capillary nose, a souvenir of his passion for single malt Scotch. He had a reputation for overlooking spotty performance in subordinate managing directors if a nubile was procured for him during a subsidiary visit.