|

Lil’s like a daughter to me. Hate to see her grieving Cam’s passing so hard. All of us are grieving Cam. He was good man. When he decided to settle in Harlan and hang his shingle after law school, he could have had any girl in this town – every single girl at Powers and Hortons, for one. He’d come in whistling, say howdy to Polly at the register and she’d blush blood like a redhead will, and then all us salesladies would hush to hear his conversation over in the men’s section. We loved him in a Schlesinger’s worsted wool, that one with the blue pin stripe comes to mind. My heart breaks for Lil, all alone. In Bible study we kept her and Cam on the prayer chain for a child, but God must have other plans. Well, she’s not exactly alone, as we all saw at the viewing tonight. Those Eastmans are a sight! Lil’s oldest sister was standing in front of Delong’s Funeral Home smoking, wearing a cheap skirt five inches above her knees. Her runny nosed brood leaning on the back of that rusted truck, parked on the sidewalk by the way, making all of us tramp through the Cotton’s front yard to get into the parlor to pay our respects. What’s bred in the bone at Harlan Gas. Cam plucked Lil up out of there, gave her a better life. Must’ve been 18 years ago Cam posted the bans at church about his intent to marry Lil Eastman. First off, it was shocking he’d finally chosen someone, since he was already in his thirties. And then an Eastman girl! Barely twenty, working at the drugstore counter. (At least Lil’s daddy was the only one in Big Jim’s brood who didn’t spend time in the courthouse basement.) When Lil walked down the church aisle on her wedding day (her daddy wheezing because of the Black Lung) I pitied her. She’d worn her mother’s dress, long sleeved, and it was June, so the flush she had on her cheeks made us all hot. We grabbed for those pew fans and beat them something furious at the sight. I thought I saw a big yellow stain on her hem, but it could have been a reflection of the gold velvet pew cushions behind her. (Thinking back on it, she should have worn a slip underneath. White satin is a tricky material.) Lil picked cornflowers from her Daddy’s house as a bouquet, and they looked as sad as they do along the side of the road. Not a lick of makeup, her long auburn hair in a thick braid down her back. She wore black patent leather shoes. With a wedding dress! The rest of her clan looked like a pile of dirty laundry in the front pew. The young’uns were wailing. When Dr. McDowell started a prayer, all of them would raise their hands, saying amen out loud. (It’s just not the way of us Presbyterians. There’s no dunking, no hollering in our church.) At the end of the ceremony, Cam said, “I’m not leaving here without kissing my bride, Pastor,” even though that certainly isn’t something we do in the sanctuary, no sir. And then he placed both of his hands on Lil’s fine-boned jaw and brought her face to his like he was drinking the cup of salvation. It was too long a kiss for anybody’s liking. No need to parade around like that. I told him that after the ceremony. And Cam smiled real big and said, Haddie, no one will put me asunder from my Lil. Well, death will. When Lil moved to Central Street, I knew the most neighborly thing I could do was to help her wring that Eastman out of her. I taught her how to be a lady, just like I taught my Bonnie Reigh. First things first, I got Cam to set up an account for her at Powers and Hortons. That Regina dress she wore tonight? I ordered that special for her, for the fall. Dark blue, two-ply poly so it holds a shape, those gold buttons up and down the bodice with gold trim, like a uniform. Had Polly shorten the sleeves since it’s so hot this summer. I’m bringing over the raw silk sheath for the funeral tomorrow. It’s plain, so I’ll tell her to wear that strand of pearls and brooch Cam gave her for their anniversary, a sensible heel that won’t sink in the ground when she’s walking to the grave, it’s been so rainy. I went over to their house with a casserole the moment I heard about Cam. Dodo was already there, tending to everything for Lil, as a neighbor should. She said Lil was resting. I told Dodo, God placed something on my heart during my morning prayer, asked her to take me to Lil. Lil was a just a puddle in the den. I took a seat on the couch next to her, hugged her close, wiped her tears, held her sweet little hand. And I said, The Lord will keep your soul. The Lord will guard your going out and your coming in, from this time forth and forever. Psalm 121, thanks be. I reached for her tiny chin, raised it, asked her to recite the Lord’s Prayer with me. Lil looked me dead in the eye like she was searching for something, started wailing like she was a lost child. Dodo gathered Lil up, took her to the bedroom. She was so long in there with her, I had to let myself out. I didn’t get a taste of Cora’s apple stack cake, or a bite of Mabel’s fudge. And if that Eastman clan has the nerve to show up at Cam’s house after the funeral tomorrow, it’ll be like the plague of locusts. Nothing will be left except the taste of our tears. Bio: Meg Artley will have her first piece of fiction published in October 2023 by Flash Fiction Magazine. After taking full advantage of the excellent craft classes at The Writer's Center in Bethesda, MD, she was invited to study with Johannes Lichtman in the Jenny McKean Moore workshop at George Washington University in the fall of 2022. "Haddie Saves an Eastman" is part of a collection of short stories she is writing about Harlan, KY in the 1970s. Sorry, my knees don’t bend that way. Shantih. Mark J. Mitchell has worked in hospital kitchens, fast food, retail wine and spirits, conventions, tourism, and warehouses. He has also been a working poet for almost 50 years. An award-winning poet, he is the author of five full-length poetry collections, and six chapbooks. His latest collection is Something To Be from Pski’s Porch Publishing. He is very fond of baseball, Louis Aragon, Miles Davis, Kafka, Dante, and his wife, activist and documentarian Joan Juster. He lives in San Francisco, where he makes his marginal living pointing out pretty things. He can be found reading his poetry here: https://www.youtube.com/@markj.mitchell4351. A meager online presence can be found at https://www.facebook.com/MarkJMitchellwriter/. A primitive web site now exists: https://www.mark-j-mitchell.square.site/ He sometimes tweets @Mark J Mitchell_Writer Drunk at noon in the city of Baudelaire, I am back at my hotel, deprived of sleep, here for an afternoon nap. I yank the curtains shut, lie down on the bed, think about all the ghosts who’ve occupied this space before me. Ghosts. I can almost see them gliding across the carpet, laughing, arguing, making love in the milky maundering moonlit hours. This hotel is ancient. It’s at least 200 years old. I can hear a strange occasional clicking inside the walls. I can hear the floors groaning. I can feel the heavy rumble of the metro as it passes underneath the building. I fold the pillow around my skull, throw the duvet over me. But after about 10 minutes, it becomes clear – I’m too wired to sleep. How can you sleep in bright liquid August in the city of Picasso, Cendrars, Hemingway? I ponder the question for a bit, though I know the answer. So, I climb out of bed - I too am a ghost in this hotel’s memory - pulling up my trousers, lacing my shoes. I grab my wallet off the dresser and, remembering I am in the city of Villon, remove bank card licenses Deutschland Ticket everything but €30 and head up to Montmartre. M.P. Powers is the author of The Initiate (Anxiety Press, Fall, 2023). Recent publications include the Columbia Review, Black Stone/White Stone, Mayday Magazine, and others. His artwork can be found on Instagram @mppowers1132. English language lamentation: mighty vocab notwithstanding! Clunky linear equations – imbued pathos not commanding. Romance linguists venire boldly; spry phonemics rattle-patter… Latin phrases comfort coldly; verbum ordo doesn’t matter. Syntaxe française quite dynamic: morphemic déclinaisons flounce. Bellas frases panoramic: Spanish dicción diphthongs pronounce. Modern word choice can constrict one, forcing language leaps to craft puns. Christopher Capri (he/him) is a poet and fiction author whose work focuses on the experiences of his LGBTQ+ community; while completing an MFA in Poetry at Lindenwood University, he is a Fiber Artist and educator, Editorial Board Member of Cicada Creative Magazine, and member of Worcester Writers’ Collective. Chris’ work has been featured in Drip Literary Magazine, Graphic Violence Lit, and Fifth Wheel Press’ upcoming Dreamland. Find out more at christophications.com. There had been an autumn, years before, when Molly had been happy. Her hair had been beautiful then, and she quite often found herself thinking about how it had cascaded over her shoulders when she’d taken it down after work, how she’d so casually twirled it around her finger when she’d had a few drinks, how drunk men looked at it, and her, when she laughed at their jokes. She was sure there had been other times throughout the decades when she’d been happy, but she found herself thinking about that hair, and that autumn, more than anything else. It was raining in the real world as she grabbed her apron and keys, and she knew that once she opened her basement apartment door the smell of worms would flood her nostrils. It hadn’t rained during the autumn when she had been happy - at least not during her waking hours. If water had dropped from the sky, it must have been the slow, drizzling morning showers that artistic people love, because they’d never been loud enough to wake her. By the time she’d get up to put her hair in rollers, the clouds were always done crying and the worm smell was gone from the world. It had been the only time she’d ever desired to own her own house because she hadn’t been imagining the soggy, writhing chunks of worms that would slide through the yard. It was autumn now, in the real world, as Molly locked the door and began her march down the sidewalk. The smell of worms writhed its way into her inhale, just as she knew they would. Cosmic tears pelted her dollar store umbrella and she wondered if she would have to stop and vomit. The town no longer felt like one she knew – and hadn’t for quite some time – but the russet, water-logged leaves reminded her of an autumn a few years after the one in which she’d been happy. The Autumn of John, she thought to herself as she gagged at the smell and tried not to look down. A limited amount of people knew about her aversion to the smell, and those that did couldn’t understand it. Whenever she told anyone, an air of pretentious astonishment would overcome them. “How could you not love the smell of rain?” they’d ask. “It isn’t the water,” she’d respond, feeling herself leave the moment, feeling herself melt away into nothing. John had been different. John hadn’t laughed when she’d told him, on that stuffy September day when she’d been wearing the shorts that everyone seemed to like the best. The radio was on, as it always was when it was slow, and when the weatherman announced a chance of rain, she’d shakily shut the sole bar window. “It might get stuffy in here,” John had hiccupped from his stool, a minutes-old rum and coke nearly empty in front of him. “I don’t like the smell of worms,” she responded, turning around to face him, her long, thick ponytail slithering over her shoulder. John shrugged, finished his drink, and handed her his glass. “Whatever you want, Molly-Cat.” She’d had sex with him for the first time that night, after her own drunkenness had caught up to his following her shift. The whiskey had started an hour before she’d clocked out and had continued for three hours after, giving her the simultaneous fire and numbness she would need to enjoy herself. It was her first time sleeping with a customer and she thought regret would soon consume her, but it never did. It rained a lot that fall. After a few storms, John started getting up to lock out the worms before Molly had even realized the clouds were darkening. Three months of sweet rum breath, closed windows, and unwashed sheets went by slowly and easily. The warm weather lingered that year, something everyone but Molly seemed pleased about. It didn’t even threaten to snow until the day before Thanksgiving, and the first flake didn’t fall until after midnight. John was drinking and waiting as Molly was cleaning and stocking. She looked out the window, at the cascade of white and the blanketed road. “So you like winter?” John asked, his words starting to slur together. She gave him a questioning look. “Just wondering,” he shrugged. “No rain in the winter.” He took a sip. “No worms.” Molly could have sworn her heart stopped beating, only to begin again, pushing brand new blood through her veins. “Do you want to come to my aunt’s tomorrow?” she blurted, clenching her fingers around the rag in her hand. John’s face – red from the rum and puffy from the coke – melted into a slow smile. His eyes held their drunken glaze, and Molly wondered if they would have lit up had he been sober. “You asking me to come to your family Thanksgiving, Molly-Cat?” Later, when the bar was clean and the doors were locked, they kissed as the snow fell on top of them. They were going to drive separately and meet at her place, as John had insisted on going home to get his best flannel for the big day. “Gotta make a good first look,” he said, brushing flakes out of Molly’s hair. “First impression,” Molly corrected, realizing she’d never been this happy in her entire life. It didn’t last, as rain replaced the snow as soon as she got home. She stared out the kitchen window, her heart rate climbing as she told herself that the worms wouldn’t be able to penetrate the icy ground, that the crystals would stifle their smell and freeze their bodies. She closed her eyes and placed her head on the cool glass, repeating to herself that John would be there soon. When she looked outside again, the snow on the road had mutated into a gleaming sheet of ice. ……………………………………………………………………………………………………… In the real world, Molly was so lost in the overgrown path of her memory that she didn’t recall a moment of her walk to work, only snapping out of her head when her hand collided with the metal door handle. She jumped, her eyes darting around the dumpsters and linen bags. Reaching into her purse, she pulled out her thermos and shook it. No slosh. She must have drunk it all on the walk, and, judging by the taste in her mouth, vomited it all back up. “Thanks to the smell of the worms,” she whispered to herself, gagging as she refused to breathe in through her nose. She hadn’t been scheduled to open today and started taking tables before checking if her coworkers needed any help. The twenty-something girl with hair like Molly had once glared at her as she greeted the twelve-top of deacons. “It sure is wet out there, eh Molly?” one of them asked. “It’s keeping things green,” she said with a closed-mouth smile. Her shift went as it normally did. None of the other servers spoke to her, and she begrudgingly told herself that tomorrow she’d have to do some side work. She figured that the twenty-something with bouncing hair and giant eyes would have no trouble convincing the owner to fire her, and that was not something she could afford. They ran out of hashbrowns at ten. The coffee machine threatened not to work at eleven. A man that looked like John ordered a tuna melt at noon. Molly bummed half a fifth from Ken the cook at one. At two, she hit $100. Later, walking home in the still-raining world, she wondered if she’d been wrong about the autumn in which she’d been happy. There couldn’t have been two of them, and she remembered being happy with John. But it had rained a lot, and she swore she recalled a stretch of weeks without the smell, could envision herself with brilliant hair and bright eyes and no worry over the worms. She stopped at the liquor store, her mind arguing with itself about when things had happened. She bought a handle for herself and a fifth for Ken. There could have been two autumns without rain, she thought as she left the store. She stopped at the trash bin at the end of the parking lot and held her head over it, opening her mouth and gagging. Nothing came out. “It rained the night John died,” she whispered as she stood. She knew his car had slid and spun and flipped, and remembered watching the rain ice the road as she waited for him. What year was that? How old had she been? She took a swig from the fifth. Ken wouldn’t mind. When she got home, she told herself, she’d look at the obituary. That way, she’d know at least one of the autumns in which she might have been happy. Lilia Anderson was named after a great-great-uncle she never met. Raised in the land of the lakes, her stories often center on stubborn people in stubborn towns. She currently lives in Denver, Colorado with a lot of books and a very handsome man. Her writing can be found in 86 Logic, Feels Blind Literary, Blood & Bourbon, and more.  There are three ways to go over, under, across the center knot, it all starts with the slip watch your master’s hands as he executes the twists and turns, motions smooth, too quick to follow – blacksmith hammer on the anvil if you don’t pick it up today, tomorrow brings another task, new loads to secure. Checkerboard moves made, no shades of gray – battles won, fortunes lost. Breathe deep, clear your mind, begin again – STEVE SIBRA grew up on a small wheat farm in North Central Montana, near the town of Big Sandy (population approximately 800 people). His work has appeared in numerous literary journals, magazines and newspapers over the past 3 decades, including Chiron Review, Jellyfish Review, Jersey Devil, Flint Hills Review and others. His full length book of poetry, Shoes For Baby, was published in 2022 by Swallow Publishing. Steve resides in the Seattle area. Already knew it, Long before I did. When told you left me, They managed to nod. Kept watching the ballgame. Spoke as little as possible-- Except to order more whisky; On my tab, of course. Can’t say I blamed the boys. Would have done the same, If they met a similar fate. Warned me, again and again, Claimed you were out of my league. Should have listened to them. Saved my folding money For more nights like these. Bart Edelman’s poetry collections include Crossing the Hackensack, Under Damaris’ Dress, The Alphabet of Love, The Gentle Man, The Last Mojito, The Geographer’s Wife, Whistling to Trick the Wind, and This Body Is Never at Rest: New and Selected Poems 1993 – 2023, forthcoming from Meadowlark Press. He has taught at Glendale College, where he edited Eclipse, a literary journal, and, most recently, in the MFA program at Antioch University, Los Angeles. His work has been widely anthologized in textbooks published by City Lights Books, Etruscan Press, Fountainhead Press, Harcourt Brace, Longman, McGraw-Hill, Prentice Hall, Simon & Schuster, Thomson/Heinle, the University of Iowa Press, Wadsworth, and others. He lives in Pasadena, California. It sits off an alley that winds off an alley halfway up the hill you climb from Akasaka to Ropponggi, cursing the layout of the subway at the end of a too long day of meetings. There are no plastic samples in a glass case outside the door just a t-shirt and beer mug, for ribs and fires don’t translate well to polystyrene and the loud oldies rock that engulfs you says it all anyway. Around the back, down still another alley, where the neon fades to partially blinding, the chef at Spago sucks on his Lucky Seven and stares at the Hard Rock Café and dreams he is Elvis. A splotch of Heinz ketchup a bit of veggie burger falls on my white cotton shirt sleeves rolled mid-forearm, while the waitress refills my Sapporo and giggles her way into the kitchen. Louis Faber’s His work has appeared widely in the U.S., Europe and Asia, including in Arena Magazine (Australia), Whisky Blot, Glimpse, South Carolina Review, Rattle, Pearl, Dreich (Scotland), Alchemy Stone (U.K.), and Flora Fiction, Defenestration, Constellations, Jimson Weed and Atlanta Review, and has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize. Travis listened to his wife Britany’s phone call. He winced. “DFS is visiting tomorrow. Now I got to clean this shithole tonight and go do laundry. That bitch social worker is gonna want to see we have some food in here,” she snapped after she hung up. Travis took a wad of rumpled one-dollar bills from his pocket and handed them to Britany. There goes my beer money, he thought. She counted all seven of them out, slamming the skinny stack on the battered coffee table. Britany glowered at him. “We need eggs, meat, fresh greens and some fruit by tomorrow, or they’ll take the kids to foster care,” she snapped. Well, maybe you should have used the EBT card for food instead of selling it for meth money, he thought. “I’ll get some meat tonight. Bowen will give me twenty bucks for tenderloins and backstraps,” Travis said, as he pulled on his Carhartt jacket and wool skull cap. “We can’t risk you coming back empty again. I’ll go get a quick fifty from Jimmy,” she said standing up. Travis flew across the small trailer living room, kicking his son’s toy truck from the boy’s hand as he lunged for his wife’s throat. His son pulled his younger sister away from the fray. Britany’s eyes widen as Travis firmly held her by the throat. “I ain’t no goddamn cuc for a meth whore. You go to him, you stay with him.” ## As the late afternoon sun painted the November sky streaks of burnt orange to the west, Travis drove down Old Mill Parkway. The road ran through a half dozen corn or soy fields then a stretch of woods along the river before it passed a new gated community of mini mansions. This close to rut the deer should be moving and some rich asshole might hit one on their way home, he reasoned. Within the first two miles, Travis found two mangled doe carcasses. Both were too old and had gone off. Travis turned onto County Road 22; he’d return to Old Mill after traffic hour in hopes somebody got unlucky on their evening commute. He knew roadkill would be harder to find out on 22, but he had a decent chance of running a deer down. Last summer, after he got probation for spotlighting deer, Travis reinforced the inside of his front bumper with steel plates he boosted from a construction site. Then he welded the bumper directly to the frame of his 1997 F150, turning it into a battering ram. Travis installed a extra bright LED light bar on his hood to “freeze” deer. Not allowed to legally hunt or own weapons, his truck was his only weapon to kill deer. Originally, Travis modified his truck hoping to run down bucks. Over his years of poaching, he had built up network of taxidermists like Bowen willing to buy buck racks, hides, and prime cuts of meat. He’d hoped the truck would provide him with stew meat and booze money. He sped through the straight section of the road that lined farm fields, knowing deer would see him coming. When the road began to follow the river, he slowed and clicked on the LED lights, hoping to catch a deer crossing. Nothing. Where the fuck are all the deer? He took County Road 34 back to the Old Mill Parkway. He spotted a buck on the shoulder, but his corpse had already gassed up. Travis pulled over. It was a decent 10-point buck. He took his Sawzall from the cab and cutoff the buck’s skull cap. Bowen will pay at least $15 for this rack, he thought. As he drove back down Old Mill Parkway, he prayed, Come on God, give me some meat. A few minutes later, he saw it; a freshly dead doe laid just off the road in a drainage ditch. Travis pulled off the road, grabbed his hunting knife, and went to work. It took him about 10 minutes to cut the backstraps, tenderloins, and hams and shoulders free, and wrap it all in a clean tarp in the bed of his truck. He’d skin the hams and shoulders back at the trailer. He texted Bowen—I’m headed your way with meat and a rack. Have cash. ## Travis left Bowen’s with $40 and two road beers, not counting the one he drank bullshitting with Bowen. He made his way to Kroger and picked up eggs, milk, potatoes, cereal, apples, greens, and a few staples. He had just enough cash left to stop at the gas station for a 40oz of Bud. When he pulled up the trailer it was dark. Britany’s beater wasn’t parked out front. Travis quietly opened the unlocked door and went in. In the glow of the TV, his son and daughter slept on a sleeping bag on the cold floor. He put the groceries away. Then went to cover his children with a blanket. As Travis bent over them, his son woke and hugged his neck. “Mommy went to Mr. Jimmy’s,” he said. Travis drew him closer. “That’s alright son, I got us a bunch of food… I got you your favorite cereal for breakfast. Go back to sleep.” Travis kissed each child on the head. He opened a beer and headed back to his truck. He took off his jacket despite the cold and went to work skinning the deer quarters. As he worked, he decided he’d make venison stew for supper tomorrow; he’d even offer a bowl to the DFS social worker. He’d ask his ma to watch the kids tomorrow night. It’s roadkill season, he said aloud. JD Clapp is based in San Diego, CA. His work has appeared in Micro Fiction Mondays Magazine, Free Flash Fiction, Wrong Turn Literary, Scribes MICRO, Café Lit, among several others. His story, One Last Drop, was a finalist in the 2023 Hemingway Shorts Literary Journal, Short Story Competition. On the side of Blackrock Village

Where nursed flowers adorn the square See visitors enjoy the spectacle Of Cork rowers on the pier. When sky is bruised and silent Up Old Blackrock Road Hear oars displace the quiet With such grace they shift their load. Olympians or enthusiasts The thrill is just the same Watch the shells fly towards Blackrock Castle And see them fly back again. Owen O’Sullivan has studied both Film Making and Photography at St. John’s Central College, Cork. His love for the Arts comes from his father who would sing the songs of Van Morrison while walking with his children around Blackrock Castle. He has been writing poetry for twelve years and has been published in Ireland, U.K., and U.S.A. He graduated from University College Cork in 2021 after studying Youth and Community and is currently coordinator for Mahon Meals on Wheels. He lives in Blackrock, Cork. I love simplicity. Life can be very complicated and stressful but if we made things simple, everyone would be happier. I have a flat with a subsidised rent; a steady job as a warehouse packer; my rent and bills paid by direct debit and enough money for a pint or two each week. I’m walking distance from work so don’t have to worry about commuting and I have access to all the books I need at the local library. I love routine. It gives me stability. There is an outdoor gym nearby and I go there every other day to keep fit and it doesn’t cost a penny. I can’t do as much as I used to mind you. I’m no spring chicken, but for my age I’m not too bad, even though I am small in size. I’ve got used to being without family so that doesn’t bother me anymore. They cut me off years ago. I don’t have any real friends but I don’t mind. I’m used to spending long periods on my own and who needs friends when you have all the books you can read; a roof over your head; food on the table and money for the occasional drink. This is what keeps me level-headed. I haven’t needed therapy or medication in years. Mind my own business and stay out of trouble. That’s what keeps me going. At least it did until I met Henrietta. We met in the park while I was resting after a bit of exercise. She just sat next to me on the park bench and started talking. I had seen her in the park a few times but never thought I would get to know her. She looked like she was in her late teens although it’s hard to tell these days. Young enough to be my daughter, that’s for sure. She seemed genuine. At one point she even rested her hand on my knee. That’s a good sign, isn’t it? She had a lovely, warm smile. We met in the park regularly and she offered to cook for me. I’ve never had a woman cook for me since I was a kid. I invited her to my flat and shortly after entering, after having a good look around, she used the bathroom. When she came out, she looked different. A bit nervous. The doorbell rang which surprised me as I never have visitors. Before I could react, she opened my front door and a group of young guys came in. Henrietta obviously knew them quite well the way they greeted her. They all seemed so tall. What are kids eating these days to make them so big? They were not friendly like Henrietta. They didn’t even acknowledge me. After a brief time looking over the flat, they started moving furniture around. I was confused and stunned into silence. As I was watching them do this, I turned to ask Henrietta what was going on but she had disappeared. I finally asked one of them what was happening and he was very rude to me. He used bad language and told me to go to my room and stay there until he said I could come out. He then produced a gun from the small of his back and told me if I said anything, he would shoot me. I don’t like violence. I know what the effects can be. I did what he said and went to my room. When he called me, he informed me that they would allow me to continue to live there but the flat now belonged to them. They would use it for business and I was to stay in my room at all times until they had all left. He warned me what would happen if I told anyone or decided to inform the police and I believed him. He made me give him my spare set of keys. His friends were calling him Topper. Things changed. They were no longer simple. I was still allowed to go to work, the library, the park and have the occasional drink, but I had to depend on Topper to know when it was ok to be in the flat. Even on those occasions, I had to stay in my room. Lots of people kept ringing the doorbell and drugs were being sold and consumed. I noticed the familiar smells. It was mainly men that came, but sometimes there were girls too. Often, when I was in my room and Topper was there with his friends, I heard lots of screaming and moaning. Sex sounds. Really disgusting. My whole life was turned upside down as I had lost control. I had been in bad situations before but I thought those days were behind me. That’s when I started to get headaches. I knew from the distant past what that meant but I was no longer on medication. I needed a release. I started thinking about coping mechanisms I had used before when I finally realised what I needed to do. On my day off work, at a time I knew Topper and his friends would not be at the flat, I took my favourite knife from the kitchen and checked it was still razor sharp. I remembered years ago, after serving 22 years, telling the parole board I had learned my lesson and had genuine remorse for the lives I took. They acknowledged I was a different person and no longer a threat. I know how to cut people. I’m very good at it. I know exactly where and how to cut to make the end come quickly for them. I’ll go in hard and fast. I’ll wait for Topper and his friends to arrive. My head is starting to clear. I’m feeling better already. Tom Matthews is a London based writer of short screenplays and short stories. His work has been published in Literally Stories magazine. Wrote the screenplay for short films The Spice of Life and The Right Candidate. Has won screenwriting awards domestically and overseas, including festivals in Berlin, New York and Los Angeles. Wind blows through my bones, pares me to a skeleton, gate-ribs shivering. Jim Friedman has been published on-line and in anthologies. He had his first collection published in 2022. He is working on a second collection. Klea grasped the pot handle of her simmering meat sauce, inhaling the robust bouquet of lamb and beef with hints of cinnamon and oregano. Lungs filled with the scent of her spell, she burst out four chords of joyous, operatic song. Proper sound was often lacking in the cooking process and it was an essential ingredient to add, activating the potential of edible magic. Tone and volume were important, as were the emotions experienced while creating it. That would be her biggest challenge today. How could she simmer in joy with grief brimming in her heart? Klea preferred her spells to be pleasant, turning down clients who sought the darker side of her witchcraft. But her practice wasn’t a quiet one. The couple next door had once threatened to call the cops on their ‘crazy neighbor’ when Klea baked a raucous batch of cookies. Klea’s father often placated them: he always had a way with people. A subtle magic that wasn’t magic, a splendid thing to behold. Dad had jogged outside, his bare feet sinking into their neatly mowed lawn as the neighbor woman shouted over her picket fence with her grouchy husband at her shoulder. He dispelled the couple’s irritation with an easy smile and a horribly bad joke. Klea had watched from the kitchen window, cookies in hand, as the neighbors’ shoulders relaxed, anger stitched into their faces softening as they spoke with him. And now dad was gone. The lawn was overgrown, weed-ridden and more brown than it should be for early fall. Klea gripped the stainless steel handle. A solid anchor—something real in a suddenly surreal world. She set the lid on top of her pot, tipped to release whispers of steam, and turned to the tall windows framing the front yard. They should arrive any time. Despite the clear skies, the world outside was gray; color leaking down drains sliced into the gutters on the lane. A quiet lane lined with cottages and old oaks where Klea and her sisters used to play as children, pretending to cast spells as if they were simple words. Magic was far deeper than that; something dad had taught them with each gentle gesture and crooked smile. Barren street too much to bear, Klea turned back to the warm light in her kitchen. But it was uncomfortably empty. She should make some tea, keep busy. She whistled along with the kettle to give her beverage a touch of cheer, but her heart wasn’t in it. Hoping for a little comfort, she hummed to the jasmine leaves as they steeped in hot water. It took a moment to realize the tune she picked was a lullaby her mother used to sing. Tears threatened her numb countenance, and she choked them back, edging away from her simmering sauce. She couldn’t taint the spell she was cooking. Not now. Not when her sisters were finally coming home. Together again after so long. She needed to be there, warm and welcoming, to ease their melancholy. A unifier to their differences. But standing in the empty shell of their house, his house, she lost that battle, and salt trailed down her cheeks to join the jasmine in her teacup. Klea stared outside, trying to occupy her mind as she waited. Squirrels foraged with less enthusiasm. A wren that hadn’t flown south pecked weakly at the brittle grass. Even the breeze jostling the fanned leaves of the ginkgo tree did so half-heartedly. Brecka used to love climbing that tree. “Aren’t parents supposed to tell their kids to be careful? To get down so they don’t hurt themselves?” Klea had often asked her father. Dad had smirked, giving a shrug as he watched Brecka dangle high above them. “I think we both know that would only push Brecka higher up the tree.” As if summoned by a thought, Brecka’s car puttered down the lane. The black beater sang in Klea’s ears like a gentle staccato as it pulled into the driveway behind Klea’s pickup. Klea wasn’t going anywhere: she never did. Klea set her mug on the counter and rushed out through the kitchen door—the screen barely swinging open before a car door slammed shut. “Traffic is still terrible,” Brecka said, her mane of raven hair tangled up in the collar of her long black coat. “It’s a one-lane road.” Klea spread her arms and embraced her sister on the cracked driveway. “It’s less a matter of how many cars, but if you’re lucky enough to get stuck behind a slow one.” She felt Brecka snort against her shoulder before withdrawing. “How are you?” Brecka asked, sharp eyes searching Klea’s face. Klea forced a smile. “I’m getting by.” Brecka jerked the stiff screen door open and waved them inside the house as if she had never left. “Sure.” Brecka could sniff bullshit a mile away. “I’m a little better now.” That was true. Brecka stepped into the kitchen. “Well, enjoy the peace while you can. Once Morraine’s loud ass gets here, that’ll be over.” She inhaled and visibly relaxed, creases of strain vanishing from the corners of her eyes. “Smells good. What spell is that?” “You know the rules,” Klea chided. “Wait until we’re at the table before guessing.” But this spell had begun the moment Brecka stepped inside. Brecka didn’t bother pressing, striding across the open floor to the den, where the family used to gather each night after dinner. “I’m surprised you haven’t started the fire yet,” she called over her shoulder. “Feel free to do it,” Klea said, keeping her voice steady. She hadn’t touched the hearth since dad passed. It was the heart of his home, the gathering place, the place to swap stories. Now, she couldn’t bear to sit in the den alone. “How’s your practice coming along?” Klea called, continuing to glance out the window for signs of the others. Brecka grunted as she hauled a few dusty logs by the fireplace onto the grate within and opened the flue. “About what you’d expect. I painted a beautiful spell of protection for a newborn last week and finished a rather special one for a cancer survivor. Also turned away some crazy bitch who thought I would curse her ex-boyfriend with…bedroom deficiencies. What about you?” This meal was the first Klea had found the strength to cook since she murmured her last goodbye. Her kitchen now sat neglected where before she had lived in it. She could still hear dad’s gentle rumble as she baked Chel’s favorite shortbread cookies, infused with warm hums of homecoming. “If you keep sending her treats, what incentive does she have to come home?” he asked, watching her wrap them lovingly in a tin with a letter asking her to visit. As Klea opened her mouth to make an excuse to Brecka, another car door slammed outside. Brecka didn’t move, fiddling with the deep box of tinder and kindling by the hearth. Klea paced towards the door, but the screen was already opening to reveal Chel’s bony face, sprinkled with its usual dusting of glitter. A large prism dangled from a golden chain around her neck, swaying like a pendulum as she leaned forward. Despite being middle-aged, Chel never grew out of bedecking herself in sparkles. She gave Klea an airy smile, pale eyes distant and gentle. “Klea,” she said. “It smells otherworldly in here. What spell is that?” “If you tell her, I’m leaving!” Brecka called from the den. Klea chuckled. “You’ll find out at the table, same as always.” As Chel reached a bejeweled hand to pat Klea’s square jaw, water built behind her sister’s thick-rimmed glasses. Klea wasn’t ready to examine those feelings and turned to check on her sauce as she swallowed a lump in her throat. The kitchen door opened again. Fauna poked her round, dark face into the kitchen, looking as wild as the woods she lived in. “I can smell that from outside,” she breathed, wide eyes landing on the stove. “Now I’m hungry.” Chel turned to usher their youngest sister inside. “Don’t let the chill in.” “She’s fine,” Klea said, wrapping her arms around Fauna’s slight frame, the girl’s knotted hair catching for a moment on Klea’s earrings. “No friends today?” “Only two. I promised they could come,” Fauna said, her tiny voice thinner than usual. “Well, I hope they’re small.” Klea leaned over to check Fauna’s person. A pair of chipmunks peeked out from the right pocket of the young woman’s oversized duster. Their beady eyes stared up at Klea expectantly. “Tell them they’d better like peanuts,” Klea said. “That’s what I have.” Dad had always kept a jar around. He would toss them to the squirrels outside while he asked Klea what names Fauna would give them if she were still home. “I think that one looks like a Nutters, yeah?” “I don’t think she names them, dad.” While her younger sister whispered to the critters, golden light licked against the walls of the den as flames consumed kindling. Eyes shot to the fireplace, where Brecka stood with a proud grin. “We got time before dinner? I could do with a story.” Klea’s heart pounded faster. “I have a few more elements to add to the spell.” She ushered the other two sisters down towards Brecka. “Go catch up; I can hear you talking from here.” It was one of the best things about their family house—the kitchen was open to everything. “Morraine’s late as usual,” Brecka said, slumping onto a hand-carved rocking chair. A chorus of creaking followed as the other two sat on the worn couch, threadbare from many years of love. Klea soaked in the song of memory: banter from her sisters, the groaning of wooden furniture, the crackling of the fire. Father’s voice reciting stories about their mother, meeting her in the forest of Cevat where the wood nymph bewitched him with more than just her words. Those tales were all they had of her now. Klea turned back to her meat sauce and opened the lid to let in the ambient noises of nostalgia, tender and bittersweet. She was careful not to stand too close, unwilling to sour it with the ache in her heart. While the three sisters chatted about their practices and recited old stories about mom, Klea worked on her spell. She whipped up a bechamel with plenty of cream, adding in nutmeg and parmesan before finishing it with a few lines from a cheerful jig. Pasta got tossed in with the meat sauce and tipped into a casserole dish, bechamel topping the hearty blend. With a whisper of love, Klea sent it to bake. As she shut the oven, the screen door opened one last time, a booming voice reverberating off her cabinets. “Sorry I’m late!” Morraine said, spreading out her arms. “Forgot how horrid the road from the airport can be.” Red lipstick painted a little too thick, mascara a touch too dark, Morraine stood larger than life. Boisterous but loving in her own way. “Brecka, dear,” Morraine called, unable to wait a second longer to antagonize her sibling. “Didn’t daddy tell you to fix that dent in your driver’s side door ages ago?” He had. But as he deducted decades before, telling Brecka to do something was like challenging her to a standoff. Something Morraine never picked up on. “How do you even know that?” Brecka muttered from the den, refusing to leave her rocker. “I know lots of things.” Morraine paused, inhaling. “Oh, Klea, it’s simply divine in here. I can taste your magic in the air. Breathtaking.” Klea bent down and cracked the oven door, letting in Morraine’s sonorous tones. That was more important for the spell than perfect heat circulation. The meal was nearing completion, almost all the ingredients added now. Fauna joined them again in the kitchen to greet Morraine and snatch another handful of peanuts for her guests. Morraine clucked her tongue. “Fauna, when was the last time you combed your hair?” “Perhaps we can help lay the table,” Chel’s gentle legato cut over Morraine’s nagging. “Unless that’s a part of this spell?” She glanced at Klea. Klea gave her a coy smile. “That would be perfect. You know where everything is, nothing’s changed.” The banter continued, strained and strident following Morraine’s arrival. It felt almost normal. Almost. It was a lie. Something unspoken lay beneath the laughter, grumbles, and shrill critiques. Something quiet and empty, throbbing like a deep drum. The absence of a low, easy baritone. Her last ingredient. Klea leaned on the speckled granite counter to steady herself. Dad had been the sole rock in her life while her sisters drifted away like dandelion seeds out into the wider world, far from hearth and home. They sent word back occasionally, but their thirst for more kept them apart, never bonding the way Klea and their father had. The sisters inherited their mother’s wild blood, veins full of wanderlust. Klea inherited her father’s sense of duty. She could never leave home, leave him; it would be too much like leaving one of her arms behind. Or, more accurately, her heart. She had wanted to draw the others back together, but nothing worked. Nothing brought them all home at once. It was their father who succeeded where she failed. “I’ll bring them home,” he’d whispered near the end. “Death can be a great unifier.” Was that his final spell? A summoning. To give Klea this last gift. Had he died just for her? Klea’s throat swelled shut; she couldn’t hold back the guilt any longer and turned aside to hide her face. But Brecka could sniff bullshit a mile away. Ink-stained arms wrapped around Klea’s stocky form. “We’re here. We came,” Brecka croaked. “I’m sorry we were too late.” That was too much. A sob pierced Klea’s safe harbor of numbness, followed by another. And another. She tried to get away from the oven; sorrow would sour the meal. Brecka held her steady, the others joining the embrace in a circle. “Your sorrow is a part of this, Klea,” Brecka said. “Our sorrow. We may not have been as close to him, but a hymn of mourning unites us, too. Complete the spell.” “We aren’t even at the table yet,” Klea rasped. “You’re not supposed to guess the spell until we eat.” “We know you, Klea,” Fauna said. “You’ve been brewing up unity since we were kids. I sensed it the moment I stepped inside.” Klea realized the oven timer was beeping—how long, she wasn’t certain—but Morraine was already opening it. “Why don’t we skip the table, dish out this succulent magic, and eat down by the hearth instead?” Morraine said. “I think it’s about time that we told some stories about dad.” Klea stared down at the den, warm and welcoming, but absent of her anchor. She knew she needed to face it. To face his empty chair by the hearth, the seat worn from daily use. To wake each morning without the pungent scent of his coffee brewing on the counter. To live in a world without his horrible jokes and warm chuckle. But she found him still in the embrace of her sisters. His smile shone through on Brecka’s face, and Fauna had inherited his inquisitive eyes. Morraine could sweet talk almost anyone and no one told worse jokes than Chel. Klea nodded. Surrounded by her sisters, she would face this goodbye. “I’ll grab some plates.” Erin L. Swann is a lifelong lover of fantasy and space adventures. She’s an avid home cook and works as an art teacher, feeding the imaginations of others while fueling her own creativity. Her work appears in numerous publications including Factor Four Magazine, The Colored Lens, and Brigids Gate Press. You can find her on twitter @swannscribbles and on her website at www.swannscribbles.com. One is ironing his habit carefully, nosing the hot tip of the iron into gathers frowning in the off-white fabric. There is a method here, a dance implicit in the movements made, stepped into many times before – hand-lift and footfall surely done. Skill focussed on the task in hand, it has the comeliness of calm performance like fruit ripening, a steady coming to the full. He parks the iron to cool down, leaving all as neat as before. Carrying the alb across his arms it looks like a limp pietà. Jim Friedman has been published online and in anthologies. He had his first collection published in 2022. He is working on a second collection. Fly you rebel, you charlatan, for who other than a trickster could feel lightness in such times as these? Although you circle and swoop, we know the world is broken. And the tears we cry at that knowledge forever stain our cheeks. Don’t shimmer in the golden glow of daybreak, don’t bring another dawn if it cannot be better than those we have already seen. I see you as you want us to – benevolent, generous – but the sheen blinds us from the truth. Yet, you touch me, and the sting of gratification inoculates my doubts, makes me want to trust. But tell me, how can we soar, how do we survive when each day whittles away our resolve. How do we overcome the burdens handed us, the holes that can’t be filled with 10,000 shovelfuls of dirt. No, even you can’t pretend that all will be well. You rise higher, but at some point, the wax will melt. David Mihalyov lives near Lake Ontario in Webster, NY, with his wife, two daughters, and beagle. His poems and short fiction have appeared in Ocean State Review, Dunes Review, Free State Review, New Plains Review, San Pedro River Review, and other journals. His first poetry collection, A Safe Distance, was published by Main Street Rag Press in 2022. I want to slam the steel tracks and bomb the railcar that’s scheduled to take you away from me. I become hard like you but not in a hotel way. The stabbing below my waist is the hate I start to have for the things I love: your five o’clock shadow, your David body, your Joker laugh, your addicting affirmations, your stare from green eyes we both share. all because I am not there, on the steel tracks in the railcar with you. Nancy Byrne Iannucci is a poet from Long Island, New York who currently lives in Troy, NY with her two cats: Nash and Emily Dickinson. San Pedro River Review, 34 Orchard, Defenestration, Hobo Camp Review, Bending Genres, The Mantle, Typehouse Literary Magazine, Glass: a Poetry Journal are some of the places you will find her. She is the author of three chapbooks, Temptation of Wood (Nixes Mate Review, 2018), Goblin Fruit (Impspired, 2021), and Primitive Prayer (Plan B Press, fall 2022). Visit her at www.nancybyrneiannucci.com Instagram: @nancybyrneiannucci when she came to leave her tearful goodbye whispered like a hand grenade Ian Gouge is an experienced author and poet with numerous volumes mainly Indie published but some with non-fiction published traditionally. i. I bowed to the crows when I realized your presence turned my eyes to tongues. Mind led where body resisted. But how could I scare something so rare? ii. Alone with you, time held a match to my belly and rusted my spine. Time was a deep sea oil spill when I had you I hemorrhaged you. iii. A lone sisserou choosing my shoulder would coo as it pleased while I’d cower, memorize its weight; wait for the talon in the collarbone. iv. You flew off before the gentle bleach of habit falling like first snow. But weren’t there others in need of technicolor and a way back home? Lindsay Clark is a resident physician living in California with her family. The formal fashion of an ode, reflection of emotive style embraces only what I know, my heart, mind, soul combined to show a sole commitment, chosen goal. Holistic, mindful, common wealth, well-being in community, these I can raise, praiseworthy whole, but ill-defined when general, an ode to everything is null, a jack of all, master of none, like prayer of child that all be blest. But poets seek to garner verse, as anglers on a sea of words, the fisherman’s hope, she or he, from depths, swirl eddies, current flow. With net or rod, can it be hooked, some darting silver, flying fish, or is it shark fin, tuna tin? To catch a Water-God, old rope, detritus or the pearl, great price, the selkie, mermaid, siren call, must rise before the squall capsize; but will it suit their palate taste? Stephen Kingsnorth (Cambridge M.A., English & Religious Studies), retired to Wales, UK from ministry in the Methodist Church due to Parkinson’s Disease, has had pieces published by on-line poetry sites, printed journals and anthologies, including The Whisky Blot. He has, like so many, been a nominee for the Pushcart Prize and Best of the Net. His blog is at https://poetrykingsnorth.wordpress.com/. Death caps mass in the rot of oakfall; nearby, a single chanterelle A lone bat flaps by-- streetlight and clapboard conjure its fleeting double Headlights lacerate heavy air, disappear; night heals without a scar Michael Rodman’s writing, including poetry and satire, has appeared in Bear Creek Gazette, Talking River Review, MAD Magazine, McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, Defenestration, Oddfellow, and elsewhere. His poem “Document (Undocumented)” was winner of the 2019 Oscar Wilde Award from Gival Press. His work has been adapted and presented onstage by Lively Productions in New York City. A native of Metro Detroit, he now lives in New Hampshire.

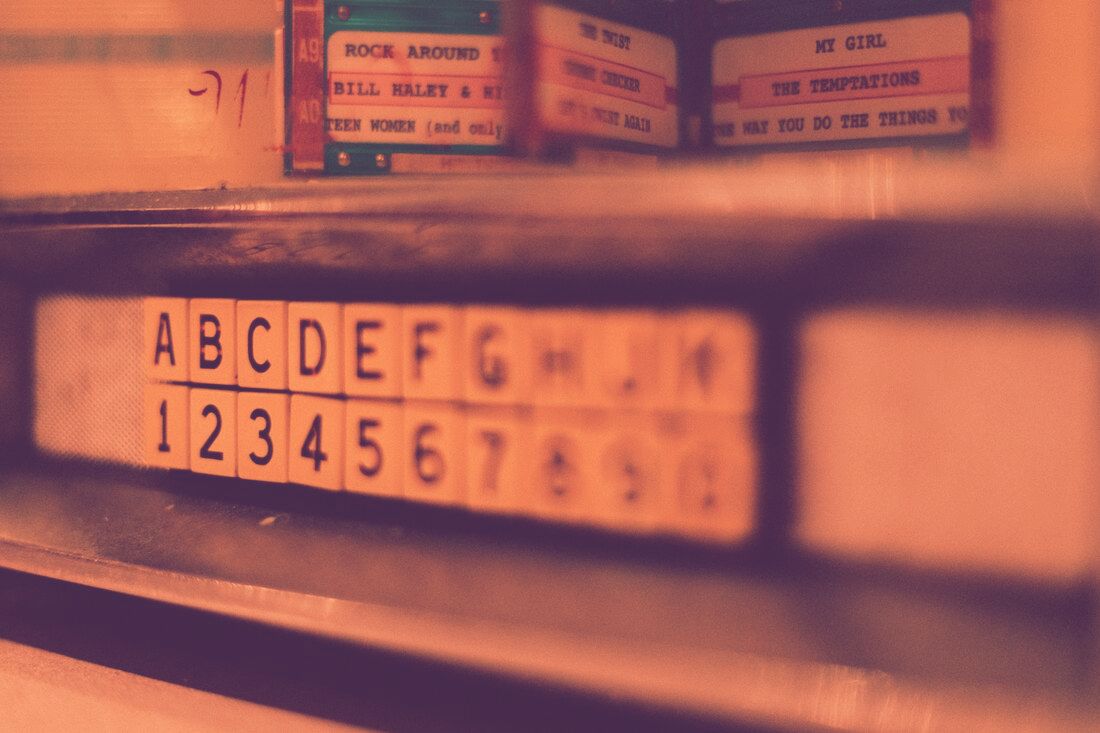

Walking through a small grove of bamboo, the breeze evokes a creaking until you need to look to insure the tall spindles are not about to collapse on you. A small child seeing you knows what you are thinking, smiles and says “they are just saying hello, so you should say hello back.” Her parents appear flustered, whether because she is talking to strangers or for fear that she is bothering you, but of course it is neither, for the girl is a Buddha dragging you into this fragile moment, so you say hello and both the bamboo and girl giggle. Louis Faber is a poet living in Florida. His work has appeared widely in the U.S., Europe and Asia, including in the Whisky Blot, Glimpse, South Carolina Review, Rattle, Pearl, Dreich (Scotland), Alchemy Stone (U.K.), and Flora Fiction, Defenestration, Constellations, Jimson Weed and Atlanta Review, and has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize. So long as I’m in the river, it doesn’t matter where I flow. Zhihua Wang’s poems have appeared in Aji, Last Leaves, Across the Margin, Eunoia Review, and elsewhere. She received her MFA in Poetry from the University of Central Arkansas and will be a doctoral student in creative writing at the University of Rhode Island this fall. I spent a pleasant morning walking quietly around the grounds, searching for them diligently, but as on most days they again remained hidden from sight. I did see several cattle egrets staring deeply into the foliage, knowing that breakfast lay hidden deep within, and a flock of ibis pecking life from the still wet, just watered lawns. Today I even saw a Great Blue Heron admiring herself in the still surface of the pond across the road, and a snowy egret and a little green heron engaged in a silent conversation to which I would never be privy, but in the glare of the morning sun, despite my careful search, not a single poem showed itself, leaving me to hope that tomorrow would bring better luck, or as least a cinquain or a ballade, not my pantoum of failure. Louis Faber is a poet living in Florida. His work has appeared widely in the U.S., Europe and Asia, including in the Whisky Blot, Glimpse, South Carolina Review, Rattle, Pearl, Dreich (Scotland), Alchemy Stone (U.K.), and Flora Fiction, Defenestration, Constellations, Jimson Weed and Atlanta Review, and has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize. To hell with deejays, live bands, crowded dance floors. On lonely nights, bourbon in hand, I still love to hunker, over wide-bellied jukeboxes tucked into dark corners of back street bars, their squat legs perched on sawdust strewn floors, their gap-toothed grin, like a fat man waiting to be fed. I flip through metal pages in search of songs from the past—downbeat Doo-wop of the fifties, Frankie Lyman wailing on that ancient question —why do fools fall in love-- the Platters, rumbling with the rhythm of sex, and Elvis, the king, high gloss, down dirty, singing, sobbing, turning us weak with desire, we wanted to be there, to live in that mysterious hotel called Heartbreak, to walk its bleak, seedy corridors until we learned it was not a place to reside forever. Elizabeth Burk is a semi-retired psychologist and a native New Yorker who divides her time between her family in New York and a home and husband in southwest Louisiana. She is the author of three collections: Learning to Love Louisiana, Louisiana Purchase, and Duet: Poet & Photographer, a collaboration with her photographer husband. Her poems, prose pieces, and reviews have been published in various journals and anthologies including Atlanta Review, Rattle, Southern Poetry Anthology, Louisiana Literature, Passager, Pithead Chapel, PANK, One Art, and elsewhere. Her first full-length manuscript will be published in September 2024, by Texas Review Press. How calmly the cubes settle in the tumbler where twilight ambers. The antidote to memory Lights the body's furnace, Banishes the cold. Once at a fetish street fair a man-sized latex egg, and in it, an alien. The barrier of skin dissolving. a wet hand digs through a breech to signal safe. I take that hand in mine. I won't let go. Darren Black resides on Massachusetts North Shore. He continues to hone his poetic skills in workshops and has studied in Vermont College's MFA program. His first publication appeared in the fall 2019 issue of the Muddy River Poetry Review. Recent poems explore disability and his own experiences living with blindness. |

Follow Us On Social MediaArchives

June 2024

Categories

All

Help support our literary journal...help us to support our writers.

|

Home Journal (Read More)

Copyright © 2021-2023 by The Whisky Blot & Shane Huey, LLC. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed